- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Classical ballet was perhaps the most visible symbol of aristocratic culture and its isolation from the rest of Russian society under the tsars. In the wake of the October Revolution, ballet, like all of the arts, fell under the auspices of the Soviet authorities. In light of these events, many feared that the imperial ballet troupes would be disbanded. Instead, the Soviets attempted to mold the former imperial ballet to suit their revolutionary cultural agenda and employ it to reeducate the masses. As Christina Ezrahi's groundbreaking study reveals, they were far from successful in this ambitious effort to gain complete control over art.

Swans of the Kremlin offers a fascinating glimpse at the collision of art and politics during the volatile first fifty years of the Soviet period. Ezrahi shows how the producers and performers of Russia's two major troupes, the Mariinsky (later Kirov) and the Bolshoi, quietly but effectively resisted Soviet cultural hegemony during this period. Despite all controls put on them, they managed to maintain the classical forms and traditions of their rich artistic past and to further develop their art form. These aesthetic and professional standards proved to be the power behind the ballet's worldwide appeal. The troupes soon became the showpiece of Soviet cultural achievement, as they captivated Western audiences during the Cold War period.

Based on her extensive research into official archives, and personal interviews with many of the artists and staff, Ezrahi presents the first-ever account of the inner workings of these famed ballet troupes during the Soviet era. She follows their struggles in the postrevolutionary period, their peak during the golden age of the 1950s and 1960s, and concludes with their monumental productions staged to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the revolution in 1968.

Swans of the Kremlin offers a fascinating glimpse at the collision of art and politics during the volatile first fifty years of the Soviet period. Ezrahi shows how the producers and performers of Russia's two major troupes, the Mariinsky (later Kirov) and the Bolshoi, quietly but effectively resisted Soviet cultural hegemony during this period. Despite all controls put on them, they managed to maintain the classical forms and traditions of their rich artistic past and to further develop their art form. These aesthetic and professional standards proved to be the power behind the ballet's worldwide appeal. The troupes soon became the showpiece of Soviet cultural achievement, as they captivated Western audiences during the Cold War period.

Based on her extensive research into official archives, and personal interviews with many of the artists and staff, Ezrahi presents the first-ever account of the inner workings of these famed ballet troupes during the Soviet era. She follows their struggles in the postrevolutionary period, their peak during the golden age of the 1950s and 1960s, and concludes with their monumental productions staged to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the revolution in 1968.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Swans of the Kremlin by Christina Ezrahi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Russian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Survival

The Mariinsky and Bolshoi after the October Revolution

Of all stage arts inherited from the past, ballet bore the largest quantity of “birth-marks” of the exploitative society…. One incontestable fact was preserved in the memory of each and everyone—ballet performances of the past were given only at the imperial theaters and they were held in the highest esteem by the tsar's family, by high officials, by the apex of the exploitative society.

—YURI SLONIMSKY, SOVETSKII BALET

ON 25 OCTOBER 1917, as Bolshevik forces were besieging the Winter Palace, the Mariinsky Theater was preparing for that evening's ballet performance dedicated to the memory of Tchaikovsky.1 Tamara Karsavina left her flat near the Winter Palace around five o'clock in the afternoon. The ballerina, who had achieved international fame with Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, was dancing that night. By many detours she arrived at the theater an hour later, but by eight o'clock, an hour after the scheduled beginning of the performance, about four-fifths of the cast were still missing. The performance went ahead, even though “the few performers on the vast stage were like the beginning of a jigsaw puzzle, a few clustered pieces here and there—the pattern had to be imagined. Still fewer people in the audience. A cannonade was faintly heard from the stage, quite plainly from the dressing rooms.”2 The capture of the Winter Palace later that night concluded the Bolshevik coup d'état and symbolized the beginning of a new era.

The Bolshevik Revolution struck the imperial theaters like a thunderbolt. Ballet had been an entertainment for the elites of imperial Russia, and its prospects were at best unclear during the assault on tradition and the clash between the old and the emerging new order that followed the October Revolution. The political, ideological, and economic consequences of the revolution put the survival of ballet into question. Not only did the ballet companies have to cope with a mass exodus of leading figures of the stage and with nearly impossible working conditions but ideological pressures emerged from the cacophony of shouts by grassroots Communists, supporters of proletarian cultural movements, and the militant artistic avant-garde who were decrying ballet as an artificial, frivolous art form—a decadent playground for grand dukes hopelessly out of touch with reality. The question whether there should be a place for ballet in the proletarian, Socialist society Bolshevism was hoping to build was closely linked to an ideological-political debate involving the regime, Russia's prerevolutionary cultural elite, and the avant-garde: What should be the role of culture in a society that was supposed to build socialism? What should be the relationship between postrevolutionary culture and Russia's prerevolutionary cultural heritage? Would there be a place for ballet in the Soviet cultural project?

The Imperial Ballet in Prerevolutionary Russia

Born at Renaissance and absolutist courts in Europe, ballet's roots as an art form are firmly planted in aristocratic soil.3 In imperial Russia, the sumptuous ballet productions at the Mariinsky celebrated the patrons of the imperial ballet companies, the tsars.4 The first professional ballet performance in Russia is said to have taken place in 1736.5 Two years later, Empress Anna Ivanovna granted permission to open a ballet school in the Winter Palace. Under continued royal patronage, ballet flourished and evolved into a well-established institution. In the nineteenth century, Russian ballet reached its golden age under the guidance of the Frenchman Marius Petipa.6 Imperial St. Petersburg emerged as the undisputed international capital of classical ballet.

For the Romanov dynasty, architecture and ballet were means of cultural self-celebration. In many ways, the academic classicism of Petipa's choreography expressed in dance the grandeur and harmony of St. Petersburg's imperial architecture. Nowhere is this aesthetic symbiosis of imperial architecture and classical ballet more apparent than in the extraordinary harmony of proportion of Rossi Street, formerly known as Theater Street, which has housed the ballet school of the Mariinsky since 1836. Rossi Street is two hundred meters long, and its width of twenty meters corresponds exactly to the height of the identical buildings that occupy the whole length of the street on either side of it.7 The yellow and white, strictly classical facades of arches and columns perfectly complement the color and style of the Aleksandrinsky Theater, located where Rossi Street meets Ostrovsky Square.

For the dancers of the Mariinsky, life revolved almost exclusively around ballet from the day they entered the doors of the imperial ballet school on Rossi Street as small children. Until the end of their careers, they would cross these same doorsteps daily, first as students and then as dancers on their way to rehearsal.8 Describing her student days around the turn of the twentieth century, Karsavina remembers: “The fashion of our clothes belonged to the preceding century, but was well in keeping with the spirit of the institution, with its severe detachment from the life outside its walls. Vowed to the theater, we were kept from contact with the world as from a contamination…we were brought up in almost convent-like seclusion.”9

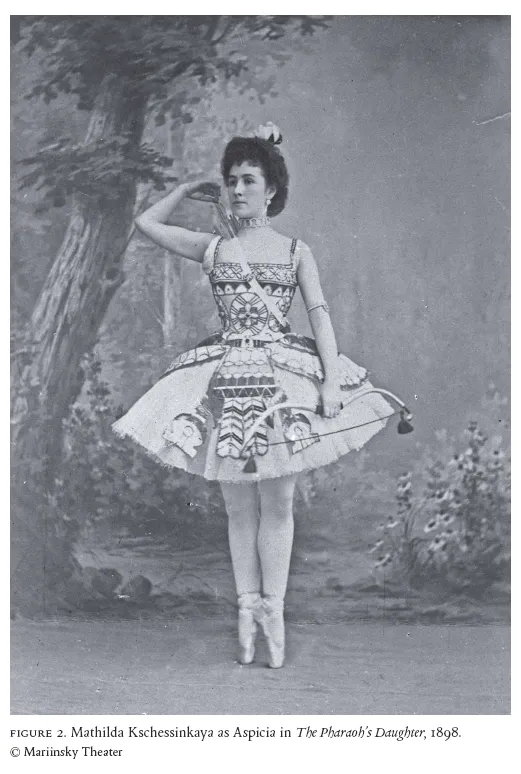

The students of the imperial ballet school were considered members of the tsar's household. On the frequent occasions when students appeared in the Mariinsky's ballet productions, court coaches emblazoned with the double eagle accompanied by liveried coachmen transported the students from the school to the theater.10 George Balanchine remembers how as a student, he appeared in Petipa's ballet The Pharaoh's Daughter on Nicholas II's name day on 6 December 1916.11 Kschessinskaya was dancing the part of the pharaoh's daughter Aspicia. The twelve-year-old Balanchine played the part of a monkey jumping through branches above Kschessinskaya, who gracefully tried to shoot down the mischievous animal with her bow and arrow. After the performance, the students who had participated in it were presented to Nicholas II in the royal box. The tsar patted Balanchine's shoulder and gave him a silver box ornamented with the imperial crest and filled with chocolates.12

From childhood, the dancers of the Mariinsky were thus reared to take their place in a tsarist institution that occupied a central position in the social life of imperial St. Petersburg. Even if by the early twentieth century the ballet audience was not completely socially homogeneous, being comprised of representatives from the nobility, foreign diplomats, military officers, and the grand bourgeoisie but also lesser officials and students,13 Kschessinskaya personified the ongoing symbiotic relationship between the ballet and its imperial patrons. Former mistress of Nicholas II, then mistress, and later wife, of Grand Duke Andrei, Kschessinskaya ruled the Mariinsky's stage. During the days of tsarist autocracy, the ballet companies of the Mariinsky and Bolshoi Theaters were jewels in the crown of imperial Russia, a dazzling entertainment reflecting the splendors of the regime. Some admirers of the ballet reached such ecstasy in their love for dance—or ballet dancers—that the term baletoman was coined to describe the delirious disciples of the imperial ballet. By declaring a war of annihilation on the political and social structure of imperial Russia, the Bolshevik Revolution aimed to turn the soil in which ballet had flourished into a wasteland.

The Mariinsky during the Civil War

Artists of the Mariinsky and Bolshoi Theaters reacted to the October Revolution with shocked hostility. By 27 October (9 November, O.S.) 1917, performances had stopped at both theaters. On 19 November 1917, the artists of the Bolshoi published a statement in Rampa i zhizn’ condemning the violence of the Bolshevik takeover of power: “Aware that we are part of a great democracy, and grieving deeply over the spilled blood of our brothers, we protest against the violent vandalism that has not even spared the ancient holy of holies of the Russian people, the temples and monuments of art and culture. The State Moscow Bolshoi Theater, as an autonomous artistic institution, does not recognize the right of interference in its internal and artistic life of any authorities who have not been elected by the theatre and are not on its staff.”14

The artists were not willing to readily accept new masters and sought to defend the theaters' artistic autonomy they had worked for since the February Revolution. The recently formed People's Commissariat of Enlightenment (Narkompros), responsible for education and culture, managed to establish contact with the theaters only after several attempts. Progress was faster in Moscow, where the Bolshoi resumed its performances on 21 November 1917 (O.S.). At the Mariinsky, some artists did not recognize Narkompros's authority until January 1918 and refused to perform. Resistance was firmest in the opera company, the chorus, and the orchestra. The ballet maintained a certain degree of neutrality: while the opera and chorus went on strike in January 1918, ballet performances continued.15 This by no means meant that the ballet had come to terms with the new situation.

Most dancers were acutely aware that their art had flourished in a world that had now been destroyed. According to Fedor Lopukhov, a leading figure at the former Mariinsky,16 director of the ballet company from 1922, and one of the most important choreographers of the 1920s, the Socialist revolution pushed the majority of ballet artists into confusion and dismay. Many dancers feared that soon they would be left without occupation in a country hostile to ballet, struggling for survival as the Russian Civil War was leading to a steady decline in living conditions: “The company seriously contracted—some grew seriously ill, some died, others left Petrograd in futile searches for a ‘quiet haven.’ Panic, terror tormented the artists of the former imperial theaters. Among them, numerous advisers from the ranks of ‘former people’ could be found who tirelessly repeated ‘One has to flee abroad as soon as possible, death is awaiting everyone.’…There were famous ballerinas and dancers who fled abroad in secret, convinced that art was doomed to death in Soviet Russia, that the Bolsheviks were ‘against art’ and so on.”17

In the years before the revolution, the Mariinsky's ballet company consisted of 212 to 228 members. By the 1919–1920 theater season, it had shrunk to 134 dancers.18 In Moscow, fewer dancers left than in Petrograd.19 The Mariinsky Ballet, however, lost approximately 40 percent of its dancers. Almost the entire Olympus of prerevolutionary ballet left Petrograd, including Mathilda Kschessinskaya, Tamara Karsavina, and Mikhail Fokine.20 Without choreographers, ballerinas, and male principal dancers, the future of ballet seemed at best uncertain, even though time would show that some of the most talented choreographers of the younger generation, such as Kasian Goleizovsky and Fedor Lopukhov, had chosen to stay in Soviet Russia.

While the dancers worried about their professional and physical survival, the new program of the Bolshevik Party adopted in March 1919 already included the seeds of a cultural policy from which ballet would benefit throughout the Soviet period: the state-driven popularization of high culture, one of the cornerstones of the Soviet cultural project. The composition of the ballet audience changed in response to emigration, social and economic upheaval, and a government policy aimed to make the theaters more accessible to the masses. The new program of the Bolshevik Party adopted in March 1919 included a section on the enlightenment of the people, calling for open access to all treasures of art that had hitherto been inaccessible for the lower classes. During the civil war period, free theater tickets were given to organizations, factories, and army units. A Soviet source from 1950 gives the following statistics: at the Mariinsky, nine opera and ballet performances were given for free to trade unions in the 1918–1919 theatrical season, fifty-six in the 1919–1920 season, and eighty-six in the 1920–1921 season. In November 1921, workers of Petrograd received 21,110 seats for thirty-eight performances at the former Mariinsky. In Moscow, 577,434 tickets for the Bolshoi and its smaller branch stage, the Filial, were distributed in the 1919–1920 season, amounting to 84.5 percent of the full house. In the 1920–1921 season, 303,218 tickets for the Bolshoi were distributed (the Filial was not working that season), amounting to 96.8 percent of the full house. With the introduction of the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921, the distribution of free or subsidized tickets was—at least for the time being—abolished.21

The practice of distributing free or subsidized tickets introduced a new, unpredictable audience to the ballet, but given the iconoclasm and vandalism of the early revolutionary period, it was far from certain how this audience would react. According to Lopukhov:

In the ballet this was a particularly dangerous moment. From time immemorial, the conviction existed that ballet is an art form “for the selected few”—for the apex of society, for the court and the aristocracy. Allusions were made that the ballet performance was born under the auspices of the courts of sovereigns; from this the conclusion was drawn that it was an integral component of tsardom. They talked about ballet's isolation from life; it was thought that, in contrast to other art forms, ballet was unable to deal with reality's stirring questions, and that it could only serve as after-dinner amusement for satiated gourmets. There was no lack of such pronouncements in the press. The more terrifying it was to wait for the reaction of the new audience.22

Lopukhov also described the backstage environment before the first performance for the new audience:

Everyone at the theater was tense to the breaking point. Some waited for the audience with agitation and hope; others—with terror; a third group calculated that this meeting would shatter all illusions and show that the artists of the ballet were not on the same path with the “rough bumpkins.”

When the auditorium, which had been intended for the “cream” of the capital's society, filled with workers and peasants in grey greatcoats, in leather jackets, in shawls—in work and war clothes, now and then even with rifles in their hands—everybody's heart began to beat anxiously…. The new audience made its appearance silently, concentrated, gloomy, as gloomy as were its clothes…. At the beginning, this silence seemed to us a manifestation of suspicion and to some—of malevolence. Only then did we understand that an unprecedented attitude to the theater was manifesting itself in this way: to the old masters, the theater was a long-known vanity fair, to the new—a previously unknown, mysterious, and agitating church.23

Lopukhov's image of the masses entering the theater like a church might be exaggerated, but they were certainly crossing a threshold into the unknown. Before the revolution, ballet as a grand spectacle existed primarily in St. Petersburg and Moscow. The audience of the imperial ballet consisted for the main part of members of the nobility, ambassadors, military officers, and the grand bourgeoisie. Moving down the social ladder—and up in the theater auditorium—one could find lesser officials, students, and, on matinee days, children. Getting a seat was not easy, and balletomanes brought lawsuits against each other, challenging the right of a subscriber to bequeath his seat to a relative or friend.24 Most simple Russians probably did not even know what exactly ballet was. After the revolution, parts of the new audience were perplexed by ballet's muteness, asking their more knowledgeable-looking seat neighbors whether the performers would soon begin to talk or sing. They marveled at the artifice of the movements and the scanty costumes of the dancers.25 But as ballet reached the factories in concerts for workers at their workplace, as free tickets for performances at the Bolshoi and former Mariinsky made ballet more widely available, awe, confusion, and maybe a desire to see skimpily dressed dancers turned into unrestrained, if at times unrefined, enthusiasm, leading a ballet critic to remark that “the nonsubscription...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on Transliteration and Translation

- Introduction

- 1. Survival: The Mariinsky and Bolshoi after the October Revolution

- 2. Ideological Pressure: Classical Ballet and Soviet Cultural Politics, 1923–1936

- 3. Art versus Politics: The Kirov's Artistic Council, 1950s–1960s

- 4. Ballet Battles: The Kirov Ballet during Khrushchev's Thaw

- 5. Beyond the Iron Curtain: The Bolshoi Ballet in London in 1956

- 6. Enfant Terrible: Leonid Iakobson and The Bedbug, 1962

- 7. Choreography as Resistance: Yuri Grigorovich's Spartacus, 1968

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1: A Who's Who

- Appendix 2: Ballets

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index