eBook - ePub

The Life and Legend of James Watt

Collaboration, Natural Philosophy, and the Improvement of the Steam Engine

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Life and Legend of James Watt

Collaboration, Natural Philosophy, and the Improvement of the Steam Engine

About this book

The Life and Legend of James Watt offers a deeper understanding of the work and character of the great eighteenth-century engineer. Stripping away layers of legend built over generations, David Philip Miller finds behind the heroic engineer a conflicted man often diffident about his achievements but also ruthless in protecting his inventions and ideas, and determined in pursuit of money and fame. A skilled and creative engineer, Watt was also a compulsive experimentalist drawn to natural philosophical inquiry, and a chemistry of heat underlay much of his work, including his steam engineering. But Watt pursued the business of natural philosophy in a way characteristic of his roots in the Scottish "improving" tradition that was in tension with Enlightenment sensibilities. As Miller demonstrates, Watt's accomplishments relied heavily on collaborations, not always acknowledged, with business partners, employees, philosophical friends, and, not least, his wives, children, and wider family. The legend created in his later years and "afterlife" claimed too much of nineteenth-century technology for Watt, but that legend was, and remains, a powerful cultural force.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Life and Legend of James Watt by David Philip Miller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Science & Technology Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One

The Making of a Scottish Improver

The port of Greenock, where James Watt took his first salt-laden breath on January 19, 1736, was then a small coastal town but very much on the rise. Located on the southern bank of the mouth of the River Clyde, twenty-five miles west of Glasgow, Greenock was in fact a recent settlement, with a population of about three thousand in 1741, rising sixfold by the end of the century. It was one of those towns created by landowners granting charters by which a group of local worthies could form a burgh council and raise taxes to develop the town. The local landowner in this case was Sir John Schaw. The granting of charters in this way indicated that landowners were seeking to turn their estates to business and profit rather than, as in the past, to military power and authority. The improving impulse that was to be so important in Watt’s life came from the top of his local community.1

The development of the town, the building of its docks and harbors, churches, schools, and civic buildings, occurred in the decades around Watt’s birth. His grandfather and father played an active role in this development. Greenock grew on account of trade, partly in agricultural products and linen (mainly with England) but increasingly, and rapidly from the 1740s, through the import of tobacco from the American colonies. By 1769 Greenock, Port Glasgow, and Glasgow handled the bulk of the Scottish tobacco trade, which in turn accounted for 52 percent of the total British trade in that commodity. The American colonies received in return a variety of basic needs channeled into Greenock by local industry and launched from its docks.2 Between 1730 and 1750 Glasgow’s colonial traders invested heavily in other manufacturing enterprises, including leather production and boot and shoe making. Textiles were another key area, especially the finishing processes such as bleaching fields and textile print-works, which required significant injections of capital. This expansion as well as trade in iron products made possible key initiatives in iron production, notably the Carron Iron Works, established in 1759 near Falkirk in Stirlingshire. Both the investors in those works and the skilled workmen often imported from England to establish and operate them represented links between Scottish economic development and the industry of the English Midlands that were to be important in Watt’s life trajectory.

Twenty years before Watt’s birth (in 1715) and again when he was nine years old (in 1745), the political settlement on which the prosperity of Greenock and Scotland was being built was challenged. The Jacobite rebellions of those years challenged the political and economic union between Scotland and England that had been sealed in the Act of Union of 1707. The Watt family, like other enterprising inhabitants of Greenock, were firm in their political, economic, and religious support of the Union. For them the Jacobites threatened a return to a less prosperous and less promising past. The future, as they saw it, lay with expanding trade and industry, enterprise and thrift. The politics of the Union, and the philosophy of “improvement” and Presbyterian accountability, ran deep in Watt’s background.3 They were thoroughly ingrained in the lives his family led and the futures they imagined for themselves. Watt’s paternal grandfather, Thomas Watt (1642–1734) was an import to Crawfordsdyke near Greenock in its early days, coming from Aberdeenshire and carrying skills as a teacher of mathematics, or “professor” of the subject as he was sometimes styled. His skills were valuable in a town with an economy based on shipping, trade, and construction.4 Whether teaching basic mensuration or high astronomical and navigational skills, Thomas Watt found a strong demand for his services. He had a house in Crawfordsdyke, then a separate burgh but subsequently part of Greenock. The fact that he owned another house besides his family residence evidences his prosperity. He had been an elder of West Parish of Greenock since 1685 and was for several years Baron Bailie (or chief magistrate) of Crawfordsdyke, denoting authority in the community as well as prosperity. Thomas Watt married Margaret Shearer in 1679, and they had six children, only two of whom reached maturity. One of these was Thomas’s elder son, John (1694–1737), who was also a teacher of mathematics and had been educated as a mathematician and surveyor. He produced a survey and map of the Clyde that was later published by the other surviving child, his younger brother James (1699–1782), the father of our protagonist.

James Watt Sr. was trained as a “wright,” or house carpenter, having been apprenticed to a John McAlpine. He married Agnes Muirhead in 1729, and between 1730 and 1734 two sons and a daughter were born, but all died in infancy; James, also a sickly child, arrived two years later. Tragedy in the loss of children in infancy and childhood haunted generations of Watts, as was common in those days even though mortality rates were improving. Amid all this, Watt Sr. became a prosperous builder. He was engaged by Sir John Schaw to extend his Greenock mansion house. Since Watt Sr. would have required financial reserves and access to credit to undertake that venture, we can conclude that he was a man of some substance. Watt Sr. also went into business as a ships’ chandler, which involved him in fitting out ships and carving their figure heads, as well as attending to the working of their instruments, compasses, and quadrants. This suggests that the family decision in 1756 to have Watt train with an instrument maker was perhaps not unrelated to the requirements and possibilities of his father’s business. Like his father before him, Watt Sr. was an important figure in the community. In fact, he was one of a select few who were entrusted with the funds raised by the community for public improvements. Thus in 1741, under the charter of the town issued by Sir John Schaw, Watt Sr. was one of nine residents selected to manage the funds raised by a tax on the malt ground in the mills west of Greenock. Ten years later, Sir John and the inhabitants of Greenock applied to the British Parliament for an act to levy a duty on every pint of ale and beer brewed, brought into, or sold in Greenock. The funds raised were to be applied to harbor repairs and to the construction of a new church, poor house, school house, marketplaces, and a public clock. Watt Sr. was one of the trustees of this fund. He also held a number of other public offices in later years. On a tombstone erected long after his death by his son, Watt Sr. was described as a “benevolent and ingenious man, and a zealous promoter of the improvements of the Town.”5

The Watts were Presbyterians, adherents of the Church of Scotland. Watt Sr. was buried not in the grounds of the church that he helped to construct but in those of the Old West Kirk that dated back to 1591 and of which his father, Thomas, had been an elder.6 We know little about the family’s religious observances, though it seems likely that their enthusiasm for the Kirk declined over the generations. Watt was to attend Kirk when in Glasgow; his payment for a pew there seems to be evidence of that. He also on one occasion told a business partner that he would be happy to experiment with him but would prefer to avoid sacrament days, “as we cannot decently try any experiment upon them.”7 After moving to Birmingham, Watt made public his Presbyterian religion seemingly only on convenient occasions, attaching himself, by all appearances, to the Church of England.8 But the old family pew, for which Watt continued to pay rent after his father’s death, was abandoned only in the early nineteenth century along with other property in Greenock.9 In a cultural sense, the family’s Presbyterianism died hard, and it left an important and lasting mark on Watt’s life and work through the moral precepts it supplied.

The harsh Calvinism of seventeenth-century Scotland softened in the early eighteenth century, rendering it reconcilable for many with thrusting commerce and, later, moderate Enlightenment views.10 Presbyterianism supported commercial activity in various ways in Scotland during the period of Watt’s youth. Not the least of the supports was the impulse that it provided to order and accountability. The inordinate influence of Scottish accounting texts in the eighteenth century has been noted. So too have the high levels of financial literacy in the population, especially among those of the “middling sort.”11 There was a related strong commercial aspect to school education. Accountability practices were central to the Scottish Presbyterian churches in their forms of governance but also, crucially, formative of individual behaviors that the church encouraged, notably confessional diaries. Also part of such individual behaviors was the careful, routine, and accurate keeping of business and personal accounts, the latter in particular as a form of moral discipline inculcated by habitual personal practices.12

This accounting habit was impressed upon Watt as a child and young man, and he in turn impressed it upon his children. We will see that such accountability issues lay at the heart of some of Watt’s struggles with his family and with his business partner, Matthew Boulton. More positively, in a way parallel to findings concerning some of Watt’s nineteenth-century coreligionists, we will see that Watt’s concerns with engine efficiency and the improvements that they impelled were also underwritten in part by this cultural Presbyterianism.13 Suspicion of trifling entertainments as a waste of valuable time, and the stoic invocation of Providence at times of loss, also came naturally to this son of Greenock.

Watt Sr.’s carefully accounted-for prosperity, then, was built significantly by servicing the ships that used the port of Greenock in plying the English and Atlantic trades. He had an interest in virtually everything that contributed to that trade, whether it was the infrastructure to support it or the commodities involved in it. From the time Watt first left home for Glasgow at the age of sixteen, through his time in London and then back in Glasgow, his correspondence with his father includes a miscellany of topics showing that both men were alert to, and concerned with, any commercial or industrial development affecting the prosperity of their community and offering an opportunity for themselves: tobacco, coal, iron, pottery, instruments, and all manner of merchant goods included. Father and son were enterprising and opportunistic to the core.14 Ventures in shipping were financially risky, and there are signs that Watt Sr. suffered a severe financial reversal at some stage, which Williamson describes as telling heavily “upon a fortune, till then in all respects adequate to the maintenance of an easy respectability.”15

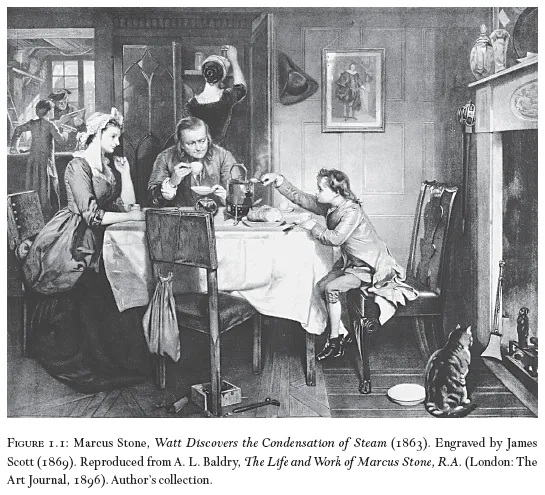

Watt’s younger brother John (b. 1739), known as “Jockey,” was also directly involved in business with his father. Marcus Stone’s well-known nineteenth-century painting of the Watt family at a table shows Jockey at the window, or counter, of his father’s business, oriented to the world of ships and the sea (see figure 1.1). Despite family trepidation Jockey went to sea as part of a trading venture to the West Indies—this at a time, the early 1760s, when there were moves to diversify a trade heavily reliant upon the increasingly fractious American colonies. Jockey drowned at sea on 30 October 1762. News from distant parts traveled slowly and uncertainly in those days. The correspondence between Watt and his father in which Jockey’s death is first feared, and its circumstances gradually revealed, shows a deep tenderness between the two men in their common loss. His father wrote: “I pray God may comfort you under the loss of so deir a brother who if he had been spaired would have been a credit & support to both you & me, but since Providence has Deprived us of that comfort we must Indivor to support it & confort on[e] another.”16 Watt, who had already lost his mother in January 1753, was to exhibit similar stoicism in the face of many other losses in his life.

What manner of child had the young James Watt been? Stone’s painting famously depicts him playing with a steam kettle under the watchful, admiring, and slightly perplexed gaze of his parents. This is nineteenth-century mythmaking rendered graphic, but the little evidence we have does paint the young Watt as a studious, often sickly, rather gentle child, teased by his more rough-and-tumble schoolmates at Mr. M’Adams’ commercial school.17 He spent much time at home with his mother, Agnes, who reputedly created a “genteel” and “orderly” domestic environment.18 At about the age of fourteen, Watt attended Greenock Grammar School under its first headmaster, Robert Arrol, a classicist and author of some reputation who published translations of Cornelius Nepos and Eutropius, the Roman historians, and also some of the colloquies of Erasmus. Whilst at that school Watt was instructed in mathematics by John Marr, who in the early 1750s was retained by the lord of the manor, Sir John Schaw, in some capacity and also appears to have had a salary from the town.19 Marr presided briefly over a very well-equipped schoolroom containing, among a great variety of instruments, a brass telescope and quadrant, and a “pair of Mr Neals Globs” as well as a good collection of books on geometry, arithmetic, trigonometry, navigation, pilotage, and annuities. At this stage of his life, his early teens, Watt was thoroughly exposed, both at home and at school, to mathematics and its practical applications. An interest in electricity, a popular preoccupation in the 1740s and 1750s, may have been encouraged in Marr’s classroom, which also contained a “frame for Electricity.”20

Until the year 1753 Watt had spent most of his time in Greenock, apart from brief trips to Glasgow to see his mother’s brother, Uncle John Muirhead, whose country estate Watt also visited. The Muirhead family was an old and distinguished one: it had contributed a number of men who held high office over the centuries and provided the bodyguard of the king at Flodden Field. More immediately, Agnes Muirhead’s father was Robert Muirhead, a merchant in Hamilton and Glasgow of whom we know little. Her brother John was later recalled as being a builder and timber merchant in Glasgow.21 The signs are that the Watt and Muirhead families were close after Watt Sr. married Agnes in 1728. Watt Sr. engaged in joint trading ventures with John Muirhead, those we know of involving salt and herrings. The two men pursued their joint activities without need of formal partnership arrangements—such was the trust between them. After John Muirhead died in 1769, the family relationship remained strong, with Watt maintaining close contact with John’s son and heir, Robert, throughout his life. Although John Muirhead’s fortunes took a turn for the worse late in his life, his son Robert inherited from him the estate of Croy Leckie in the parish of Killearn, Stirlingshire. That estate was located on the River Blain (or Blane) near its junction with the River Eldrick and about four miles east of Loch Lomond. It had been owned by John and Agnes’s father, Robert, who had been responsible for substantial planting improvements, especially on the fifty acres around the mansion house.22 His mother’s family both historically and during his young years were clearly a cut above the Watts, economically at least. We know from the testimony of John Muirhead’s daughter Marion (later Mrs. James Campbell) that the young Watt had substantial exposure to their way of life, spending some summers at her father’s house near Loch Lomond, presumably on the Croy Leckie estate.23

Many of the stories told of Watt in his younger days rely upon Marion Campbell’s recollections. She describes him as a “sickly, delicate child” taught reading by his mother and mathematics by his father. She tells a number of stories that address the capabilities of the young Watt. First, there is the tale of the visitor to the Watt household when the boy was six who reproached his parents for not sending Watt to public school, only to find that the child’s seemingly idle chalking on the hearth was in fact a precocious exercise in trigonometry. The visitor withdrew his criticism and concluded that this was “no common child.” Then, there was his practical manual prowess: “His father gave him a set of small carpenters tools & one of James’s favourite amusements was to take his little toys to pieces, reconstruct them, & invent new playthings.” His powers of “imagination & composition” were illustrated by a story of him staying for a while with some friends of his mother’s when he was about thirteen. The friend was relieved when his mother recovered him because the whole family was deprived of sleep, having been kept awake until late at night by Watt’s humorous, dramatic, and compelling storytelling. Then, of course, there is the famous kettle anecdote in which Watt, aged fifteen, is having tea with his Aunt Muirhead, who scolds him for his idle playing with the kettle, lifting its lid, capturing steam in a cup, letting it play upon a spoon, and watching it condense.24 The account continues: “It appears that when thus blamed for idleness, his active mind was employed in investigating the properties of steam. . . . Once in conversation he informed me that before he was [fifteen] he had read twice with great attention Gravesand’s Elements of natural Philosophy, adding that it was the first book upon that subject put into his hands, & that he still thought it one of the best.” The book must have been the recent popular English translation of Willem ‘s Gravesande’s Elements of Natural Philosophy that was widely admired for its presentation of the foundations of Newton’s mechanics through experimental demonstrations.25 We are told that when a little older and in Glasgow with his Uncle Muirhead, Watt read and studied a great deal in chemistry and anatomy, showing particular interest in “the medical art.”26 A strange, gory tale has him carrying off the head of a dead child for dissection. In a more bucolic vein, the time Watt spent in the summer months at Croy Leckie on the shores of Loch Lomond saw every excursion as an occasion for research into the botany and mineralogy of the area. He also studied the p...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1: The Making of a Scottish Improver

- 2: Improving Ventures: Civil Engineering and Steam

- 3: Birmingham, Boulton, and Steam Enterprise

- 4: Watt as Natural Philosopher: The Experimental Life

- 5: Team Watt: Collective Genius

- 6: The Fruits of Success

- 7: The Living Legend

- 8: Afterlife: A Man for All Causes

- 9: Concluding Reflections on the Great Steamer

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index