- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Theory and Experiment in Syntax

About this book

This book reflects on key questions of enduring interest on the nature of syntax, bringing together Grant Goodall's previous publications and new work exploring how syntactic representations are structured and the affordances of experimental techniques in studying them.

The volume sheds light on central issues in the theory of syntax while also elucidating the methods of data collection which inform them. Featuring Goodall's previous studies of linguistic phenomena in English, Spanish, and Chinese, and complemented by a new introduction and material specific to this volume, the book is divided into four sections around fundamental strands of syntactic theory. The four parts explore the dimensionality of syntactic representations; the relationship between syntactic structure and predicate-argument structure; interactions between subjects and wh-phrases in questions; and more detailed investigations of wh-dependencies but from a more overtly experimental perspective. Taken together, the volume reinforces the connections between these different aspects of syntax by highlighting their respective roles in defining what syntactic objects look like and how the grammar operates on them.

This book will be a valuable resource for scholars in linguistics, particularly those with an interest in syntax, psycholinguistics, and Romance linguistics.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Three-dimensional syntax

1 Coordination

Extract from Chapter 2 of Parallel structures in syntax: Coordination, causatives, and restructuring

1. Extraction

1.1 Coordinate Structure Constraint

- (166) The Coordinate Structure Constraint

- In a coordinate structure, no conjunct may be moved, nor may any element contained in a conjunct be moved out of that conjunct.

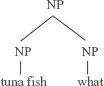

- (167)

- *What did George eat tuna fish and __?

- *Who did the mailman see __ and his wife?

- *I know a book which the senator wrote an article and __.

- (168)

- (169)

- *What did Mary cook the pie and Jane eat __?

- *Who does Tom like __ and Larry hate primates?

- *This is the man who it was raining and Bill shot __.

- (170)

- What did Mary cook the pie?

- What did Jane eat t?

- (171)

- Mary cooked the pie

- What did Jane eat?

- (172) *How loudly is John sick and moaning __?

- (173)

- How loudly is John sick?

- How loudly is John moaning t?

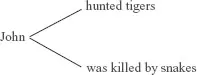

- (174) John hunted tigers and __ was killed by snakes.

- (175)

1.2 ATB exceptions to the CSC

- (176)

- Which man __ ran the race and __ won the prize?

- Which film did the critics hate __ and the audience love __?

- How loudly is Mary screaming __ and John moaning __?

- (177) unless the same element is moved out of all the conjuncts

- (178)

- Which man t ran the race?

Which man t won the prize? - Which film did the critics hate t?

Which film did the audience love t? - How loudly is Mary screaming t?

How loudly is John moaning t?

- Which man t ran the race?

1.3 Extraction in Palauan

- (179) *[a delak [a uleker er ngak [el kmo ngngera [a sensei a milskak a buk] mother asked P me COMP what teacher gave book

me [a Toki a ulterur __ er ngak]]]]

and Toki sold P me

‘My mother asked me what the teacher gave me a book and Toki sold me _. ’

- (180) [a delak a uleker [el kmo ngngera [lulterur __ a Toki el me er ngak] me mother asked COMP what sold Toki come P me and

[a Droteo ulterur __ el mo er a Toiu]]]

Droteo sold go P Toiu

‘My mother asked what Toki sold __ to me and Droteo sold __ to Toiu.’

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Introduction: Five themes in the study of syntax

- Part I Three-dimensional syntax

- Part II Syntax and argument structure

- Part III The syntax of subjects and wh-dependencies

- Part IV Constraints on wh-dependencies

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app