![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Release

WHEN I TOOK my backbench seat on 2 February 1990, the first-sitting day of a parliament to which I had been elected for the first time some five months earlier, South Africa was on the brink of transcendent change. Quite how transcendent it would be was about to be revealed in the opening speech of the newly elected president, FW de Klerk. Unbeknown to me then, I would sit through nearly twenty more such presidential addresses in the future. None had the thermonuclear intensity of De Klerk’s announcements that Friday morning in the national legislature in Cape Town; indeed, its after-effects are still being felt today.

In the 1989 election, De Klerk’s ruling National Party (NP), to whose leadership he had been elected earlier that year after his strongman predecessor, PW Botha, had been felled by a stroke, polled less than 50 per cent of the total vote. In what was to be the last all-white election (held in parallel with elections to the separate Coloured and Indian chambers), this was its lowest haul of the poll in a generation or more. He had lost ground mostly to the far-right-wing Conservative Party (CP), which obtained around 30 per cent of the votes. The reform-minded, liberal Democratic Party (DP), in whose various iterations I had been involved for much of my then-young life (I joined at age eleven and became an MP at thirty-two), brought up the rear with 21 per cent. However, the delimitation and vagaries of the constituency system allocated the NP a comfortably bigger overall majority in the new parliament than the voting totals suggested.

But De Klerk was not simply hemmed in by his own electorate and his party’s declining fortunes within it. On the one hand, the NP held a near monopoly of formal political power, bolstered through its control of the security forces and the doctrine of the supremacy of parliament, which meant even the most independent-minded judges (of whom there were a few) could only on occasion ameliorate, rather than strike down, legislation or executive acts.

On the other hand, however, as legendary US President Lyndon B Johnson once observed, ‘power is where power goes’, and, by the time the tricameral parliament was summoned to hear its new president, much of the power in South Africa had haemorrhaged from its formal structures. ‘People’s power’ was on the march in cities and townships, galvanised by an increasingly assertive trade union movement and an even larger and loosely led (to avoid government crackdowns) civic formation, the United Democratic Front (UDF), which both gave voice to an increasingly militant and still formally powerless black majority, and acted as a sort of internal Doppelgänger for the still-banned African National Congress (ANC).

Outside South Africa, the ANC in exile in Lusaka and elsewhere had become ever more vocal and effective in unleashing a campaign for ‘people’s power’ against both the authorities of the apartheid state and its many internal black allies. It was engaged in an increasingly bloody and vicious fight in my home province of Natal with its major opponent there, the Inkatha movement of Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi.

I, in common with many others, observed of the internal state of emergency imposed by the government on most urban areas, coupled with a growing international campaign of isolation, sanctions and disinvestment, that South Africa was a country at war with itself and bereft of international allies. This was no exaggeration. The ferment in South Africa was mirrored by the end-of-regime events in Eastern Europe and beyond, where the once-mighty Soviet empire began to crumble and the Berlin Wall had fallen just months before. Freedom was definitely, although unevenly, on the march and its nemesis, tyranny, was in headlong retreat. But where the chips would fall in South Africa remained the key, unanswered, question of the day.

De Klerk had provided some clues in the months between his election the previous September and his debut speech in parliament as president on 2 February that he was going to change the predictable and wearying terms of political trade in South Africa, perhaps best described as hesitant reforms hedged by lashings of repression. He had, for example, already released from life imprisonment nine major ANC leaders, first Govan Mbeki and then eight others, including Walter Sisulu and Ahmed Kathrada. Also, days after the election, he overruled his securocrats and allowed a mass march, led by two of the major internal figures of opposition, the clerics Desmond Tutu and Allan Boesak, to proceed without police interference. He also dismantled the key internal military, and secretive, apparatus, the National Security Management System, established and empowered by his predecessor, PW Botha, who placed great faith in military solutions to primarily political problems.

But it still remained far from clear that De Klerk, whose ascent to power had been marked by his careful cultivation of conservative credentials, would ‘go the whole hog’ and commence direct negotiations with the major banned black opposition movements, whose most significant component, the ANC, could not operate, or even legally hoist its banner, on home soil. Its key leader, Nelson Mandela, remained in prison, and the question and terms of his release remained the standout issue of the day.

Unknown to those of us outside the walls of state and ANC power, there had been a flurry of secret meetings between high-end government officials and ANC exiled leadership. And Mandela, who had, in December 1988, been transferred after medical treatment from Pollsmoor prison to the relative comfort of a warder’s house at Victor Verster prison outside Paarl in the Western Cape winelands, had himself been involved in several years’ talks with state officials, led by Justice Minister Kobie Coetsee. He had also, it was later revealed, enjoyed a recent, apparently pleasant, tête-à-tête with PW Botha himself, at which the president had poured the tea for his guest, by then the most famous prisoner in the world.

This is a thumbnail sketch of the background canvas on which De Klerk was to paint his outline for his country’s future that morning in parliament. Few in the chamber or outside it knew just what bold brushstrokes he would use.

From my perch right at the back of the vast parliamentary chamber, but with a clear view of the podium from where he spoke, I studied the new president closely and recorded my impression of him as he began his game-changing speech:

De Klerk, superficially, seemed both self-confident and grounded; he bore no chest full of medals; carried no homburg hat; nor did he strut with the overbearing sense of self-importance I had long associated with the leadership of the ruling party. Yet when he stood behind the podium of parliament and in increasingly assertive cadences buried the apartheid way of doing business forever, he seemed immensely elevated and strong.1

The speech lasted for not much longer than forty minutes, and with the flourish of a theatrical showman, or seasoned trial lawyer, he saved the most dramatic and far-reaching announcements for the end: a moratorium on the imposition of the death penalty, the acceptance of a negotiated new constitutional order with all leaders and, as a consequence of this, the unconditional release of Nelson Mandela in the very near future – as well as the lifting of all legal and other prohibitions on the ANC, Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), South African Communist Party (SACP), Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu), United Democratic Front (UDF) and allied organisations.

Actually, for all its stupendous impact and the political courage it took to conceive and implement it, the opening line of De Klerk’s address contained a half-truth or a white lie, when he proclaimed: ‘The general election of 6 September 1989 placed our country irrevocably on the road to drastic change.’2

In truth, his election campaign and the mandate he obtained from it were far more ambiguous. Even in my own constituency of Houghton, where he addressed an election meeting (to no avail for his party’s candidate who got an electoral thrashing a few days later), De Klerk pilloried my party as guileless satraps of the banned ANC. But, by combining the total votes of the NP and DP in his speech, he co-opted, ex post facto, a mandate for irrevocable change. A former leader of the opposition, Frederik Van Zyl Slabbert, who had imploded his own parliamentary career by resigning from the same chamber just four years earlier, waspishly observed later: ‘There is ample and comprehensive evidence that De Klerk’s speech on 2 February … was a sell-out of everything the NP had held near and dear since 1948.’

But this noting and protesting (the essence of which the Conservative Party and other elements of the then-strong forces of white right-wing reaction in South Africa were to denounce vehemently, and some even violently reject, in the following years) mattered little. De Klerk had gone where no white leader with power had ventured before. And now the pivot, and the attention of the world, turned towards another, very different, political figure – Nelson Mandela.

To this day, a debate continues on what led De Klerk to dismantle the house of privilege and racial domination he had been bequeathed. He himself later said that he saw ‘only disaster if [we] had dug in our heels’.3 Emboldened by the collapse of Communism, and the lessened fear of its takeover in South Africa, he decided to press ahead. In an interview twenty years later, in 2010, he claimed that his conversion to the politics of negotiation was neither a Damascene epiphany nor a retreat; rather, according to his version, his speech that day was the ‘conclusion of a gradual process’.4 Others suggested that he had little option, and his contribution to history was to have the intelligence to read the proverbial writing on the wall and, in direct contrast to his predecessors, not to assume it was addressed to someone else.

Of all the dramatic announcements that De Klerk made on that day, perhaps the singularly momentous one was the imminent and unconditional release of Mandela. For most of my life – and for all South Africans aged under forty or so – Mandela had been, literally and figuratively, the political equivalent of ‘the king across the water’ – or the expanse of sea between the Cape Peninsula and the grim Robben Island prison where he had spent nineteen of his twenty-seven years’ incarceration. He was, at once, both the most spoken-of and the most distant of the many figures who dominated the political landscape. But dominate from a distance, unseen except by a select few, he certainly did.

In 1964, I was just seven years old, in the second year of primary school in Durban, when Mandela had been sentenced to life imprisonment. Years later, as a student at the left-leaning University of Witwatersrand (appropriately, one of his alma maters) in the 1980s, I had involved myself in the seemingly audacious ‘Release Mandela’ campaign in which members of the student body went about with petitions demanding the release of the imprisoned icon. It had – like smoking marijuana or furtive sex – elements of the daring and illicit about it, and it proved (or improved) one’s radical chic credentials. But of the man in whose name we collected signatures, we could see no picture, nor could we read (legally at least) any of his movement’s literature.

Even back then, though, and based on the information that could be gleaned, I decided the socialist and even militant ANC held little appeal, and that it offered few viable solutions to creating the conditions for inclusive economic growth and democratic freedom that South Africa needed. My deep and abiding dislike of the narrow racial nationalism of the regnant National Party did not, unlike so many of my fellow students, lead me to adopt its opposite in the form of the ANC. The middle ground occupied by liberal and reformist movements such as the Progressive Federal Party (precursor to the Democratic Party) might have lacked the outlaw radical dash and glamour of the movements in exile, with their imprisoned leaders. But on its duller, yet, I thought, surer ground I pitched my political tent.

However, whether you were a close ANC camp follower or as distant from his movement as I was, Mandela exercised a magnetic pull on most politically conscious imaginations.

In the nine days between De Klerk’s detonating his big bang in parliament and Mandela’s designated release date, I joined my country and its people in wondering just who would emerge from the gates of the Victor Verster prison and what he would say. I also knew that, from that moment on, nothing in South Africa would ever be the same.

I subsequently learnt that all manner of arm-wrestling between De Klerk and Mandela had occurred when they met a few days later: where and when he was to be released apparently led to heated disputes between the two leading figures on South Africa’s political stage. De Klerk apparently wanted him flown to Johannesburg almost immediately, while Mandela wanted to walk out from his Paarl prison and then address the people of Cape Town. Not for the last time, the prisoner was to prevail over the president.5

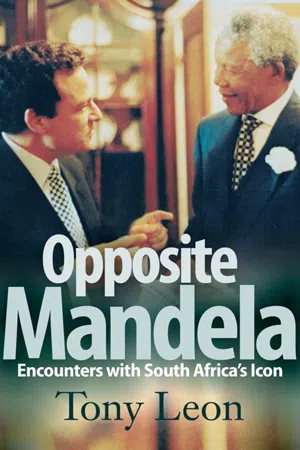

I was quite shocked when I saw a photograph of the encounter the next day; the body language looked very stiff and strained – not surprising, in view of the tensions later revealed of that encounter between them. Mandela flashed a pro forma smile while De Klerk looked peevish, as though he would rather be anywhere else. But I was more struck by both the gauntness and great age of Mandela, then seventy-one, who was showing some signs of his 10 000 days in jail. Before this, the only photographs in circulation had been taken almost three decades before, and they portrayed a bearded and obviously much younger man with a chubby face. The other noteworthy feature from this historic and uncomfortable photo opportunity was how Mandela physically towered over De Klerk. This physiological fact would, over time, serve as a sort of political metaphor for the years that were to follow.

The meaning of the moment when, two days later, Mandela finally walked out of Victor Verster prison, a free man ‘re-joining a country which had grown up without him’, is vividly captured by his authorised biographer Anthony Sampson:

Mandela walked out of the prison gates on 11 February, holding hands with [his wife] Winnie. It provided the most powerful image of the time, ...