![]()

1

‘Where forgetting resides … ’. Twentieth-century sites of violence and present-day sites of memory: A global vision from the Spanish case

Antonio Míguez Macho

The era of justification

In the era of memory, as our period has come to be known, it seems paradoxical that the most frequent phenomenon is forgetting: our societies encourage the forgetting of pasts that are traumatic, uncomfortable and not very practical for the purposes of the present. This is why we often feel disorientated when we move across the inhabited/uninhabited spaces of our cities and our countryside. We are continually in need of a guide: Google Maps to determine our location and give directions, a QR code to tell us what we are seeing, Tripadvisor to justify our journey according to the opinions of others. Spaces force us to materialize memory and therefore constitute a fascinating field of study.

It was a French sociologist, Maurice Halbwachs, who was the first to perceive the topophilic potential of memory. He also understood that memory not only refers to individual remembering, but is a construct in which the processes of social construction, shared meanings and policies of commemoration converge as well. Halbwachs’s ‘discovery’ took place in the post-First World War historical context. In fact, his life was marked by the Franco-German rivalry for a territory, a space, in dispute (Alsace and Lorraine) that changed hands twice during his lifetime. It was German when he was born – an occupation that resulted from the Franco-Prussian War – it became French after the Great War but returned to German control at the end of his days in the Second World War. The death of the Frenchman in Buchenwald after being arrested by the Gestapo is the perfect example of those wars. His life is summed up in the question: ‘how did war twice encounter Halbwachs, and how did he twice live and understand it?’.1

The semantic load of places as memory spaces is a characteristic that arose in the profoundly shaken world of post-war Europe through the public authorities’ policies of commemoration. In the First World War, military cemeteries were institutionalized, realizing the idea that those who fought together would lie for eternity together. They constituted the number one space for the modern worship of the ‘fallen’.2 Meanwhile, the need to face the reality of the absence of bodies, frequently buried in distant places, or to make the thousands of disappeared present in some way became clear.3 In 1920 the Cenotaph was inaugurated in Whitehall, London: the prototype of the empty tomb, the place that commemorates all places.4 It was a monument that was replicated in every town and square in France, Italy and Portugal, amongst many other countries, accompanied by lists of those who had died for the homeland.5 These lists were expanded and expanded again with each new conflict.6 As if that were not enough, the great powers still wanted to highlight the enormity of the sacrifice and its ‘just memory’ even further. In Duaoumont and Hohenstein, Pétain and Hindenburg inaugurated the great ossuaries in 1927.7 It is these magnificent monuments to the dead that magnify and justify their sacrifices.

Until the beginning of First World War, the main liberal states had been engaged in a process of nationalization built on the basis of great figures who represented the milestones of the homeland. The statues and monuments erected in the main European capitals between the end of the eighteenth century and throughout the nineteenth century are testimony to this: the equestrian statue of Peter the Great (the Bronze Horseman) in Saint Petersburg, Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square, the Vendôme Column crowned by Napoleon in Paris, and the equestrian statue of Frederick the Great in Unter der Linden. In revolutionary periods, this monumentalization was briefly dedicated to the people, as an agent of social transformation. Examples of this include Goya’s masterpieces on the Spanish uprising against the Napoleonic invasion or the evolution immortalized in the Arc de Triomphe from its conception in the Napoleonic period to its inauguration in 1836. The initial recognition of revolutionary citizens in the Arc de Triomphe’s sculptures was finally transformed into the tastes of the post-revolutionary era. Beyond these ephemeral yet transcendental revolutionary moments, up until the First World War, the way to commemorate the myths of nation-building was based on exceptional kings, soldiers or heroes, rather than the faces of anonymous citizens.8

The memory regime established in Europe after the end of the First World War, for its part, is defined as a regime of justification. The move to total war and the never-before-seen number of victims caused by the confrontation that broke out in 1914 changed everything. Nation states turned their efforts to providing a sense of justification for the sacrifice of the hundreds of thousands of young men on the fronts of Europe. The protagonists of memory became them, those who had ‘died for the homeland’, in the cenotaphs, cemeteries, memorials and Te Deum that were repeated annually.9 Dates of national commemoration were also established, for instance Armistice Day on 11 November, with the objective of giving meaning to the magnitude of the massacre: ‘Armistice Day was part of a sustained and creative effort to give meaning and purpose to the terrifying and unexpected experience of mass death.’10

Although all these experiences were common to the countries that had fought in the conflict, those that did not fight in the Great War were not totally left out of these changes either. Other experiences of mass violence precipitated the emergence of the new regime of justification memory, as in the case of Spain after the civil war (1936–1939). Until then, the memory regime prevailing in Spain did not differ substantially from what had been the norm in European states before 1914. Following in the wake of European countries, at the beginning of the twentieth century there was a true monumentalist outpouring. Monuments and place names were dedicated to what were considered great milestones of Spanish nation-building. The cities and towns of Spain were filled with references that ranged from the resistance of the Celtiberians against the Romans to the war against Napoleon, including figures of the great kings, warriors and heroes of all time.11

Thus, when the Second Republic was proclaimed, the prevailing memory regime in Spain was fundamentally one of nationalization with liberal nineteenth-century roots. Within this framework, the nascent Republican state began to exalt its own heroes. This was done with the ‘heroes of Jaca’, for example, a group of officers who failed in an attempt to proclaim the Republic only a few months before it was established by much more peaceful means. Spanish cities and towns were filled with streets, squares and monuments dedicated to the ‘heroes of Jaca’, frequently replacing the pantheon of names from the monarchical period. This fact was not only due to the effusiveness of the moment but also to the lack of consistent alternatives. Spain had not gone through the First World War and its only deaths for the homeland were those of the colonial wars, which were not at all an excuse for national consensus and recognition.12

Figure 1.1 Falangists (Spanish Fascists) after the triumph of the Coup in Vigo (Galicia, Spain), c. 1936. © Histagra Collection / Histagra Research Group.

With the coup d’état of July 1936 and the ensuing civil war, Spain had its experience of mass violence. The military coup leaders took control of large swathes of Spanish territory: Galicia, in the northwest of the peninsula; Castilla La Vieja, Navarre and Álava in the northern plateau; Extremadura in the east; and western Andalusia in the south down to the Portuguese border; as well as the Spanish protectorate in Morocco, the Canary Islands, and the island of Mallorca in the Mediterranean. In these territories, the newly established military regime abolished all pre-existing constitutional rights and guarantees. Mass incarceration began of all those who were deemed enemies. Within this category, the coup leaders included political militants from leftist organizations, unions and parties, but also those from moderate centrist and conservative organizations. Legitimate authority figures, civil governors, mayors, military members who were not part of the coup and public officials from all branches of the administration were subject to immediate persecution. The coup leaders also persecuted people who fell into the category of ‘anti-Spain’ because of their ideas, attitudes and public presence in the fields of culture, education and the arts. This group included those considered enemies of tradition, Catholicism and the reactionary values that the coup plotters defended. The arrests were followed by military summary trials with no guarantees of any kind for the defendants that resulted in severe sentences: from life imprisonment to the death penalty. Meanwhile, many of the detainees were removed from prison to be killed on the outskirts of towns and cities, against cemetery walls. In the summer of 1936, the appearance of corpses in roadside ditches was a daily occurrence. Many of the victims were buried in mass graves. The climate of terror that prevailed was intensified by the beatings, humiliations and purges that expelled hundreds of thousands of people from their jobs. Under military authority, and in collaboration with state security forces and squads, the practice of violence was carried out by various militia units, chief amongst them the Falange (the Spanish branch of the Fascist Party).13

As this process unfolded in the areas controlled by the coup plotters, a political and social revolution broke out in the territory loyal to the Republic. Various trade unions and militias took control of public order. They retaliated against military members and security forces sympathetic to the coup, as well as against prominent figures associated with the Right: landowners, politicians and militants of conservative parties, along with members of the clergy. This violence was concentrated in the period between July and November 1936, at which point the Republican government gradually brought public order under its control. From then on, although the violence in the Republican rearguard did not completely disappear, it lost much of its intensity.14

In the territory under coup control, the violence continued its systematic development during the war, spreading to the areas that were gradually conquered by the coup plotters thanks to their military superiority and the support of their German and Italian allies. Makeshift prisons gave way to an extensive network of 400 concentration camps.15 The persecution and purging followed systematic rules aimed at eliminating those deemed enemies of the coup in order to build a ‘new Spain’. The coup plotters who finally triumphed in 1939 made every effort to commemorate those who had died ‘for God and for Spain’: the dead soldiers of their own army. Similar to the end of the civil war in Finland in 1918, the victors of the so-called Spanish Civil War created a memory of exclusion.16 In reality, it seems more accurate to point out that this was a way for the regime to express the justification of its victims, ignoring of course the soldiers of the other side. The war’s defeated at that time were confined to concentration camps or had already been tried, sentenced and executed by the regime’s firing squads.17

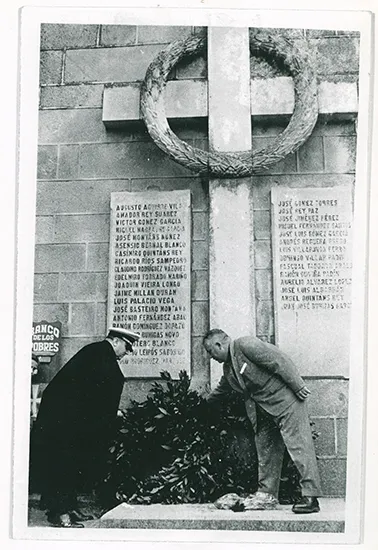

Through regulations issued in 1938, as the war was still going on, it was decided that a list of the ‘fallen’ should be placed in each town and parish of Spain.18 All of these lists were preceded by the name of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the founder of the Falange, considered to be the first of the ‘martyrs’.19 In 1940 work also began on the large construction project for the Valley of the Fallen, a building of fascist aesthetics that was erected some forty kilometres from Madrid through the slave labour of Republican prisoners. It was originally designed as an immense ossuary with a connected basilica dedicated to the ‘martyrs of the Crusade’, which became the tomb of José Antonio himself.20

Figure 1.2 Tribute at the ‘Cross of the Fallen’ in Santiago de Compostela (Galicia, Spain), civil war years. © Histagra Collection / Histagra Research Group.

In addition to building this monument, the Franco dictatorship carried out an active policy of resignification of public space in the early 1940s. The names of streets and squares in tribute to the liberal-Republican tradition were replaced by new ones dedicated to exalting the values of the homeland, Christianity and the very figure of Francisco Franco, the dictator. The emblematic premises and buildings of political parties, unions and civil associations linked to that same world of political pluralism and the already long-established Spanish liberal tradition were also seized and looted. These buildings frequently ended up in the hands of the Spanish Falange – the sole party – and its related organizations. In other cases, they ended up at bargain prices in the hands of individuals or companies that made their fortune with the new regime.21

The predatory desire of the Franco regime towards public space also extended to the figure of the dictator. Amongst many other private assets that made up an immense private fortune during their long years in power, the Franco family acquired valuable properties that they used for their own personal enjoyment. To acquire them as property, Franco used a series of tricks such as the ...