![]()

1

Exploiting nature – The early modern environment

Chapter Outline

Situating the chapter

Narrative

Nature’s mysteries

Mapping and claiming – Understanding land

Sailing the seas

Oceans of riches

Using and owning land

Competing for land

Poor Europeans

Cities – covering the land

Little Ice Age

Nature’s bounty

Flora and fauna

Plant life

Sugar

Potatoes

Monoculture

Deforestation

Animal rights

Spicy meats

Animal control

Tragedy of the Commons

Conclusion – ‘Fighting terrorism since 1492’

Keywords

Further reading

Situating the chapter

Humans have always exploited and altered the environment. Our cognitive faculties enabled us to imagine changed surroundings, and then act to make them happen. Though they were weak powers in 1492, Western European states in this era began to chart, comprehend and measure geographical distances in new ways by 1750. Mariners and innovators made use of earlier innovations – derived from Islam, Africa, China and India – to sail the seas, and then to exploit and reshape traditional societies around the world in ensuing centuries.

Britons in this period had not yet developed their particularly calculated, profitable – utilitarian – attitude to land use and global land grabs. They remained committed to the preservation of nature locally, as did most people on earth across Afro-Eurasia and the Americas. The famed Japanese Haiku poet Basho (d. 1694) exalted a similar awe of the environment (and the importance of rest from life’s travails).

From 1750, however, the small island of Great Britain, with relatively few people, would reshape the global environment more than any other by industrializing in the 1700s. This geographically tiny, unimportant nation, riven by internal conflict, would after 1750 become an imperial power and unleash the Industrial Revolution, the greatest assault on the environment in human history, prompting a world of rushed days, rushing power and, ultimately, the rush to modernity. In the nineteenth century, Japan too would industrialize at a great pace, with immense consequences for twentieth-century world history, as we shall see.

But first, between 1500 and 1750, the stage would have to be set for this dramatic transformation of human existence, mostly in societies far from England.

By the end of this chapter, readers should be able to:

• Understand how humans altered their environment in the early modern era.

• Suggest ways diverse populations made use of land and labour.

• Explain the consequences of greater global interaction for various societies.

• Appraise the effects of new connections on populations worldwide.

• Analyse whether connections were positive or negative for humanity.

Narrative

European avarice prompted the exploitation of new lands, particularly in the Americas. This spurred the development of a new harsher form of enslavement for African people, and the eradication of millions of indigenous Americans. By the twentieth century, Europeans had turned this zeal for exploration and profit towards Asia and the wider world. Once Western Europeans set foot in the Americas, new conceptions of life on earth emerged. European expansion in the early modern world set off a biological and geographical revolution, the environmental consequences of which we are still dealing with today.

Nature’s mysteries

In 1968, the biologist Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb. He warned that humans might be on the verge of destroying life on earth through ceaseless population growth. Ehrlich predicted that the sheer number of humans, combined with overconsumption of nature’s bounties, would condemn humanity to the way of the dinosaurs. Since then, global population has climbed from under 4 billion to 8 billion people, and the earth has been scarred and abused ever more. However, there have also been impressive attempts to reduce the damage of human actions. Persistent environmentalists have reshaped attitudes towards nature’s limitations, and exposed the costs of the human capacity to exploit nature. Still, human births continue apace, putting increasing pressure on the earth’s resources.

In the early modern era, the idea of overpopulating the planet seemed incomprehensible. The ecological bounty of the Americas nurtured millions of new lives, bringing forth a great population boom between 1500 and 1750, even accounting for vast deaths of African and American natives. Increasingly productive, effective use of the land in these centuries brought increases in food supplies, in lifespans and material expectations. Also, in this era, some began to grasp for the first time the great diversity of human societies inhabiting an increasingly connected earth. Few, if any, understood that nature was an active, dynamic linked system of species and processes that humans could defile.

By 1750, Europeans developed ever more efficient – if ultimately harmful – ways to exploit nature. A new moneymaking ethos, premised on a profit-seeking world view, propelled westerners to draw on the resources of all continents, primarily, if not wholly, for their benefit. Only around 1750 did some begin to slowly recognize the ethical and practical necessity of preserving lands and ecosystems for future use.

But well before Britain’s late-eighteenth-century Industrial Revolution began polluting the planet at unprecedented levels, some English land lovers warned of overexploiting the earth, lettering the first known environmental tracts. In 1661, John Evelyn, in his ‘Inconveniencie of the Aer and Smoak of London Dissipated’, wrote of the negative health effects of smoke, arguing that planting trees would correct over-logging of native forests and improve London’s dirty air:

I am able to enumerate a Catalogue of native plants, and such as are familiar to our country and clime, whose redolent and agreeable emissions would even ravish our senses, as well as perfectly improve and ameliorate the Aer about London.1

By the 1760s British ecologists inaugurated the first focused attempts to protect forested islands in the Caribbean. In the late eighteenth century, Romantics and early environmentalists warned human actions were despoiling nature, and began to spread ecological awareness through poetry and print. These early environmentalists could not prevent vast levels of pollution between 1750 and the present, of course. At be st they could slow the juggernaut of modernity that has now brought the world to possible environmental catastrophe.

Mapping and claiming – Understanding land

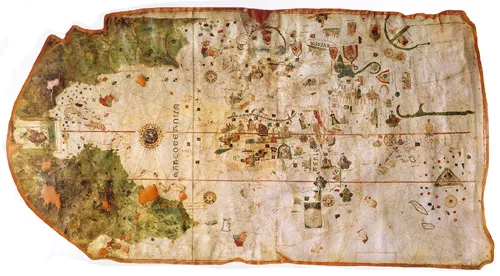

If there is one historical fact that most westerners know, it is that Christopher Columbus ‘discovered’ the Americas in 1492. The word ‘discovered’ implies that indigenous people did not know of their own existence. Native Americans had, of course, discovered the land millennia before Columbus stumbled upon the New World, unintentionally exposing Europeans to previously unknown peoples and unfamiliar lifeways, while exposing indigenous people by the millions to deadly diseases (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 De la Cosa’s map (Wikimedia Commons).

Columbus, like many early modern sailors, had little grasp of where he was going upon setting out. Sailors lived in a world of local geographical awareness, lacking accurate maps to guide them much further afar. The bounty of foodstuffs that would fill the bellies of much of the world for centuries to come was the result of wandering adventurers without a strong sense of their destination. What sailors such as Columbus did know about global navigation was mostly borrowed from knowledge developed by Muslim, Indian, African and Asian societies in previous centuries.

Indeed, the map Portuguese sailors relied on for the first all-important European voyages was made in Spain in 1375, by Jewish cartographers drawing on accounts of Muslim travellers interested in African gold and slaves. This was not simply a European endeavour, though they improved upon earlier efforts. The famous map of De la Cosa, from 1500, is thought to be the only map made by an individual who witnessed Columbus’s voyages. Such visuals were more than the first attempt at mentally mapping the Americas; they were the first step towards recurrent European visits, colonization, settlement, centuries of exploitation of American people and resources, and at times genocide.

In the early modern world, though, geography consisted of a great deal of fantastical guessing. The English hero-pirate Francis Drake mistakenly assured himself in the 1570s that he had found a waterway to sail through the Americas, inspiring others over centuries to seek a passage through the Americas that did not exist (only with the opening of the Panama Canal in August 1914 could ships actually pass through the centre of the Americas). The art of mapping, and cartography as a science, remained essentially unchanged from ancient Greek, Islamic or Chinese efforts. Most were highly inaccurate.

This was a mental environment in which apparitions populated forests, demons haunted the outskirts of villages and monsters churned in the uncharted seas of unknown depths. Unbridled imagination and impossibly long distances shaped a world view that seems innocent to us today. It nonetheless brought the most important coming together of peoples in history, the Columbian Exchange. After European sailors stumbled into the Americas in the late fifteenth century, an incredible transatlantic exchange of ideas, goods and diseases began. This exchange benefitted Europeans above all, helping fuel a slow rise to Western global dominance that is only now shifting.

More accurate attempts at mapping and demarcating brought Western states new lands in this era. In the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, the Catholic Church and its staunch allies, the monarchs of Spain and Portugal, stamped claims on all lands west of an imaginary line down the Atlantic Ocean. As a result of this claim, in the long run, all of South and Central America would speak Spanish or Portuguese, and practice Catholicism. Other European landings in the Americas also had great impact over time. In 1497 John Cabot, an Italian adventurer living in England, raised investment capital from businessmen to fund exploration of what is today Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. Most Canadians and Americans now speak English as a result.

Native peoples in the Americas possessed remarkably different approaches to the natural world than did Europeans. The Aztec, for example, believed – like pre-Christian Europeans and countless societies worldwide throughout history – in respecting the fragility of the natural world, rather than exploiting it for profit. For the Aztec, the sun, wind and most importantly water (in the form of lakes, rivers and seas and rain) represented forces that must be respected to ensure long-term survival. Dual devotion to sky and soil symbolized a holy life-giving force. Many cultures saw caves as the uterus of the earth. The earth’s resources were not to be exploited in any way but a sustainable one. This was an environmental perspective that long predated modern, Western environmentalism.

After 1521, Hernan Cortes’s defeat of the Aztec Empire challenged this Native American world view forever. Spain’s growing dominance in the Americas and subsequent European mapping of continental lands initiated both a de-sacralization of lands and the ascendancy of an exploitative, utilitarian approach to land use. For early modern Christians, land was a gift from God, meant for them to control and exploit. Mapmaking, by using empirical methods and observation, helped Europeans understand geography and advance knowledge through science, with grave consequences for millions of indigenous people. Scientifically inclined Catholic Jesuit priests in the seventeenth century even mapped the Sonora desert in North America. They then worked to visualize and record parts of India, China, Japan and the Amazon. More accurate mapping fuelled Western domination.

Europeans wandering afar in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were remarkable only because elites in complex societies throughout Eurasia typically disdained exploration in this era. Inquisitive westerners arriving in Asia were at best humoured, rarely respected. Chinese or Japanese emperors had no desire to explore...