- 79 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pepe le Moko

About this book

Vincendeau's analysis places 'Pepe le Moko' in its aesthetic, generic and cultural contexts, ranging from Duvivier's brilliant camera-work, to Gabin's suits and the film's orientalist setting. In the BFI FILM CLASSICS series.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

A CLASSIC FRENCH FILM

1. Julien Duvivier and French film noir

Julien Duvivier's critical reputation has had its ups and downs, but in the 1930s he was one of the top-ranking French directors. Initially a stage actor, Duvivier trained as assistant director to Marcel L'Herbier and Louis Feuillade, among others, before directing his first film in 1919. He made seventeen silent films, but his career really took off with sound, and he became one of the leading French mainstream film-makers until his death (in a car crash induced by a heart attack) in 1967. He directed more than sixty films, many of them highly successful commercially, both before and after the war. The most notable are David Golder (1930), Maria Chapdelaine (1934), La Bandera (1935), La Belle équipe (1936), Pépé le Moko, Un carnet de bal (1937) and La Fin du jour (1938) in the 1930s, and the Don Camillo films in the 1950s.7Duvivier is one of those film-makers who ensured the continuity that characterises classic French cinema8 from the coming of sound to the arrival of the New Wave. He was also remarkably cosmopolitan, working in Germany, Czechoslovakia, Britain and the US as well as France. Celebrated for his professionalism, rigorous planning and virtuoso technique, Duvivier was often compared to an American studio director. Indeed, unusually for a Frenchman, he was quite successful in Hollywood, where he directed five films before and during the war: The Great Waltɀ (1938) and Tales of Manhattan (1942) did particularly well at the box-office; he also made Lydia (1941, a remake of Un carnet de bat), Flesh and Fantasy (1943), and The Impostor (1944, with Jean Gabin); he also worked, uncredited, on a few other US features.

Traditional film history thinks of Duvivier as an excellent 'craftsman' and 'artisan' (or, less flatteringly, 'workhorse' and 'yeoman') rather than an auteur. In the film industry, such categorisations mattered less than reliability and results. On Duvivier's arrival in Hollywood in 1938, King Vidor praised him for his ability to work fast and economically: 'Un carnet de bal was made in six months, cost $100,000 and was a great success in Europe. pépé le Moko [...] was made for only $60,000 and yet is a work of high standard.'9 Duvivier secured some of his success by adapting literature of proven appeal, from thrillers like Pépé le Moko to popular classics such as Zola's Pot-Bouille (filmed in 1957). Like a French Michael Curtiz, he worked in a bewildering variety of genres, from biblical epic (Golgotha) to thriller (La Tête d'un homme [1932], Pépé le Moko), episode film (Un carnet de bal and Tales of Manhattan) to comedy (the Don Camillo films). He made propaganda films, especially Catholic commissions in the silent period, and two war-time propaganda films: one in France, Untel Père et fils (1940), and The Impostor in Hollywood.

But while all this points to the identity of a 'journeyman', Duvivier's status and the absence of major studios in France meant that for most of his career he had control over his material. He took an interest in professional matters,10 occasionally acted as producer and wrote or adapted most of his scripts. He formed creative teams which ensured him more power and continuity in the fragmented French industry – for instance with scriptwriters Charles Spaak and Henri Jeanson, set designer Jacques Krauss, and stars Harry Baur and Jean Gabin. Like most French directors, Duvivier was in control of the découpage (shooting script), lighting set-ups, and editing of his films, above the technicians, however prestigious, and above the will of producers. As he said, 'I always personally decided the way a particular topic would be treated [...] I always remained in control of the films I directed.'11 Thus, despite his eclecticism, it is not surprising to find strong themes and visual features running through Duvivier's work. In the second half of the 1930s in particular, he developed his own brand of populist melodrama with his Gabin trilogy of La Bandera, La Belle équipe and Pépé le Moko. What I call 'populist melodrama' is more commonly known as Poetic Realism, a key artistic sensitivity in French 1930s cinema, literature, popular music and photography.12 Poetic Realism refers to the lyrical ('poetic') depiction of everyday situations, set in working-class or lower middle-class milieux, acting out tragic or melodramatic stories on the margins of the law. But whether we call them 'populist' or Poetic Realist, Duvivier's films of the late 1930s were central to the elaboration of the aesthetics of French film noir, itself an important influence on American film noir 13 Pépé le Moko may at first sight seem less central to Poetic Realism than Carné's Le Quai des brumes (1938) and Le Jour se lève (1939), because it is removed from the French working-class urban environment. But in its dazzling black-and-white visual poetry and in its pessimistic tone, including nostalgia for a lost world of the French working classes, it is a founding keystone of French noir cinema. Four features of Duvivier's work are key to this aesthetic: an expressionist use of mise-en-scène in its interaction of lighting, performance and decor, the depiction of popular criminal milieux, a deep-rooted pessimism, and a penchant for 'men's stories'.14 These all found a particularly felicitous terrain in Pépé le Moko, as we will see.

Pépé le Moko offers an anthology of camera angles and movements, editing, lighting and music then in use in the best of the French cinema, as well as of Duvivier's virtuosity.15

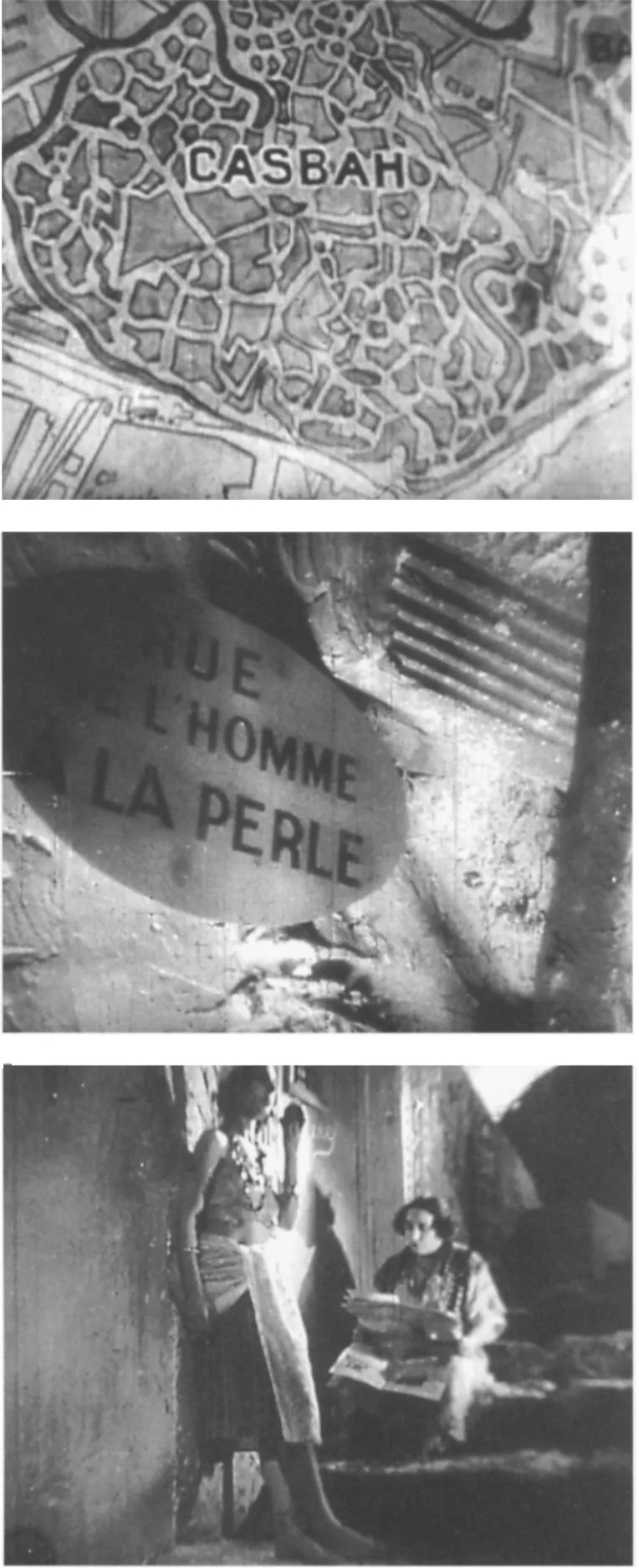

The novel opens with petty crook Carlo ('Carlos' in the film) hiding in Marseilles cheɀ Pépé's mother, Ninette. Carlo escapes to Algiers and takes us into the Casbah to meet Pépé. The film, on the other hand, begins with a map of the Casbah and remains in Algiers until the end, moving back and forth between the Casbah and the modern town (the police headquarters and the Hotel Aletti). The camera pulls back from the map to reveal a room in the police headquarters in Algiers; the exotic location is signalled by half-lowered Venetian blinds, silhouetted palm trees outside the windows and a couple of inspectors fanning themselves with their hats. As the policemen of Algiers explain to their visiting Parisian colleagues the reasons for the continued failure to capture Pépé, the dialogue establishes both his status as caïd (chief) and the centrality of the Casbah, his hideout. A 'documentary' montage then depicts the Casbah, before moving on to the 'fictional' Casbah. The progression from map to documentary to story reveals both the film's desire to anchor itself in the real, and its trajectory towards fantasy.

Images from the Casbah: the map, 'strange' street names, 'all sorts' of women

Coded as documentary with location shots, rapid editing and Inspector Meunier's authoritative voice-over, the montage (which lasts just under two minutes) shows off Duvivier's virtuosity and acts as a matrix of thematic and visual motifs for the rest of the film. The first image, a sweeping panoramic long shot of the Casbah from the top of the hill down to the harbour, encapsulates Pépé's desired journey as well as his fate. This is followed by a very fast montage of short takes (on average less than three seconds each), the camera moving from overhead shots to views down narrow alleyways, to close-ups of faces, to blurred low-angle hand-held shots which simulate the position of a person caught in the bustle of Casbah streetlife. The theme of entrapment, which began with the map showing the Casbah as enclosed fortress (the original meaning of 'Casbah') and labyrinth, is fleshed out in the montage and will be pursued across the film: we see confined, dark spaces, bars on windows and arches across streets, sinuous alleyways (the camera movement espousing their shapes), crowded cafés, a maze of split-level homes and terraces and an abundance of stairs. This is reinforced by the commentary, sprinkled with expressions such as 'tortuous and dark streets', 'tiny trap-like streets', 'holes', 'ant-hill', 'tight labyrinth'. The montage establishes straight away the colonialist notion of the Casbah as starkly alien to the Parisian inspectors and, by extension, to the viewers. Some street names picked out by the camera are simply declared exotic by the commentary ('rue de la Ville de Soum Soum'), while some link to the story to come: 'rue de l'homme a la perle' anticipates Pépé's very first appearance, holding a pearl in his hand, and his connection with Gaby and jewels; 'rue de l'impuissance,' his blocked future. The sequence ends on another major colonialist theme, the identity of the Casbah as feminine and sexual, a feminine sexuality marked as illicit since it is identified with prostitution: 'girls from all countries, in all sorts of shapes'. This in turn foreshadows the larger prostitution sub-text of the film: Pépé's discreet coding as pimp, Gaby's identity as high-class prostitute. The camera and voice-over's derogatory insistence on old, fat prostitutes will be echoed in Tania and Mere Tarte.

The novelist Italo Calvino said: 'Having seen the Casbah of Pépé le Moko, I began to look at the staircases of our own old city with a different eye [...]. The French cinema was heavy with odors whereas the American cinema smelled of Palmolive.'16 The evocative quality of the Casbah in pépé le Moko raises questions about the orientalism of the film which will be examined in Chapter 3; but it is also an index of the strong presence and materiality of the film's decor. The sets built in the Joinville studios for pépé le Moko were extensive and spectacular, and the decision to go for a reconstruction on such a scale, even if in part due to contingencies,17 was unsurprising for the time. Rene Clair's Sous les wits de Paris (1930) inaugurated a Trench school' of set design for the sound cinema, led by émigré designers Lazare Meerson and Alexandre Trauner who both taught or influenced other practitioners, among them pépé le Moko's designer, Jacques Krauss. The characteristic quality of this school was its combination of painstaking fidelity to real cityscapes (usually Paris) with subtle, poetic abstraction. While the use of sets was largely dictated by sound technology, the French school turned them into an aesthetic tool. Many fervently defended the superiority of sets over location. Leon Barsacq (who designed the sets for Renoir's La Marseillaise and Duvivier's Pot-Bouille among others) even argued that '[t]he decor of pépé le Moko, which reproduces Algiers' Casbah, has an evocative power that location shooting does not possess', because the real location would 'dissipate the viewer's interest with its involuntary picturesqueness'.18

Duvivier, in fact, was familiar with North African locations, as he had shot large sections of Les Cinq gentlemen maudits (1931) in Morocco and La Bandera in the Sahara. But these are adventure films calling for outdoor scenes, the first with depictions of religious ceremonies and the estate of colonialist Harry Baur, the second with the portrayal of legionnaires' lives. Duvivier inserted some location views of the Casbah in pépé le Moko beyond the opening montage. In the scene that follows Pépé's first encounter with Gaby, in which he gazes at the sea and Ines puts her laundry out to dry, the switch from the establishing location shot to the closer studio shot is evident, as it is in the later scene on the terrace of the Hotel Aletti. This takes in the harbour (location), and moves on, following Slimane, into a studio shot of Gaby and her friends at table. These location moments are brief, though. Sets fitted better an urban topic like Pépé le Moko and the majority of the Casbah views were recreated in the Joinville studios. Jacques Krauss was used to working with Duvivier, having designed the sets of Le Paquebot Tenacity (1933), Maria Chapdelaine, La Bander a and La Belle équipe. Trained as a painter, he reproduced the look of the Casbah streets with a meticulousness and, despite Barsacq's assertion, a love of picturesque detail borne out by a comparison with contemporary postcards (bearing in mind the self-selectivity of these postcards, designed for tourists). While providing local colour, the sets facilitated the highly controlled interaction between decor, camera and characters that distinguishes the best of French cinema of the time and which Duvivier's fluid camerawork brilliantly exemplifies. A scene early on in the film, in which Pépé and Slimane take a walk, throws into relief this tight triangular relationship.

The scene begins outside Inès' front door, where Pépé and Slimane humorously discuss Pépé's sex-appeal, while Pépé's acolytes Max and Jimmy silently watch (these two will not utter a word during the whole film). Their conversation is covered in one take of 25 seconds from a high angle medium-long shot. They move on, and the camera, from a reverse low angle position, picks up Pépé and Slimane on the stairs at the top of a steeply inclined street. They move down the street, at a leisurely pace, preceded by the back-tracking camera, as Pépé greets people standing by the side of the street. The two men pause by a house corner on the left. They resume walking and then pause a second time, as Pépé eats a kebab from a stall, he and Slimane framed by an overhead arch. Max and Jimmy continue to shadow Pépé: Jimmy plays with his bilboquet (cup-and-ball) to the right, Max stands smiling to the left. A string of peppers spans the arch diagonally, adding depth of field. They resume their walk, the camera preceding them again, and pause a third time to the right, to let a flock of sheep move up the street. Pépé eats something (a cake?) from a stall to the right. After the frantic montage described earlier, and the night-time police raid (analysed later), the function of this scene is to display the 'ordinary' bustle of the Casbah, with people and animals milling around, and Pépé's easy relationship with Slimane. Throughout the scene, the camera is mobile, imitating a passer-by and intensifying the movement of the street, as people move in the opposite direction. The scene also testifies to the literal and metaphorical closeness between Pépé and the Casbah. He addresses people and they repeat his name, like an incantation. He touches them on his way down. The design and positioning of the walls and arches tightly encase him. The three pauses show this closeness in more detail: Pépé touches the walls, slaps the hand of a stallholder, prods Slimane. He is in touch with, and at home in, the Casbah. As we will see in Chapter 4, the remake Alg...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- The Plot

- 1 A Classic French Film

- 2 A French Gangster Film

- 3 A Tale of Two Cities: Algiers and Paris

- 4 The Other Pépés

- 5 Conclusion

- Notes

- Credits

- Select Bibliography

- Also Published

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Pepe le Moko by Ginette Vincendeau in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.