eBook - ePub

Beyond the Betrayal

The Memoir of a World War II Japanese American Draft Resister of Conscience

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Beyond the Betrayal

The Memoir of a World War II Japanese American Draft Resister of Conscience

About this book

Beyond the Betrayal is a lyrically written memoir by Yoshito Kuromiya (1923–2018), a Nisei member of the Fair Play Committee (FPC), which was organized at the Heart Mountain concentration camp. The first book-length account by a Nisei World War II draft resister, this work presents an insider's perspective on the FPC and the infamous trial condemning its members' efforts. It offers not only a beautifully written account of an important moment in US history but also a rare acknowledgment of dissension within the resistance movement, both between the young men who went to prison and their older leaders and also among the young men themselves. Kuromiya's narrative is enriched by contributions from Frank Chin, Eric L. Muller, and Lawson Fusao Inada.

Of the 300 Japanese Americans who resisted the military draft on the grounds that the US government had deprived them of their fundamental rights as US citizens, Kuromiya alone has produced an autobiographical volume that explores the short- and long-term causes and consequences of this fateful wartime decision. In his exquisitely written and powerfully documented testament he speaks truth to power, making evident why he is eminently qualified to convey the plight of the Nisei draft resisters. He perceptively reframes the wartime and postwar experiences of the larger Japanese American community, commonly said to have suffered in the spirit of shikata ga nai—enduring that which cannot be changed—and emerged with dignity.

Beyond the Betrayal makes abundantly clear that the unjustly imprisoned Nisei could and did exercise their patriotism even when they refused to serve in the military in the name of civil liberties and social justice. Kuromiya's account, initially privately circulated only to family and friends, is an invaluable and insightful addition to the Nikkei historical record.

Of the 300 Japanese Americans who resisted the military draft on the grounds that the US government had deprived them of their fundamental rights as US citizens, Kuromiya alone has produced an autobiographical volume that explores the short- and long-term causes and consequences of this fateful wartime decision. In his exquisitely written and powerfully documented testament he speaks truth to power, making evident why he is eminently qualified to convey the plight of the Nisei draft resisters. He perceptively reframes the wartime and postwar experiences of the larger Japanese American community, commonly said to have suffered in the spirit of shikata ga nai—enduring that which cannot be changed—and emerged with dignity.

Beyond the Betrayal makes abundantly clear that the unjustly imprisoned Nisei could and did exercise their patriotism even when they refused to serve in the military in the name of civil liberties and social justice. Kuromiya's account, initially privately circulated only to family and friends, is an invaluable and insightful addition to the Nikkei historical record.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Beyond the Betrayal by Yoshito Kuromiya, Arthur A. Hansen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University Press of ColoradoYear

2022Print ISBN

9781646423729, 9781646421831eBook ISBN

9781646421848Beyond the Betrayal

The Memoir of a World War II Japanese American Draft Resister of Conscience

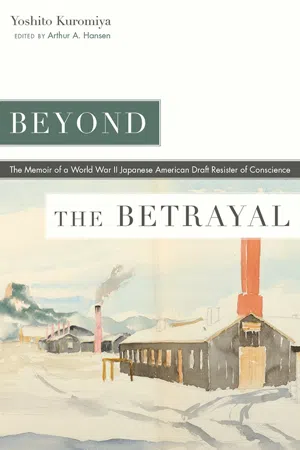

Figure 1.1. The Mountain. Watercolor by author, 1943 (Division of Political and Military History, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution).

1

In the Beginning

August 1942. We arrived at Heart Mountain in the middle of a dust storm and none of us knew what to expect. We certainly didn’t know some of us would become prisoners of war, war heroes, draft resisters, or even deportees. As a nineteen-year-old junior college student from California, I was awestruck to suddenly find myself somewhere in Wyoming as a “person of Japanese ancestry.” As in a strange dream, my US citizenship had vanished and in its place were rows upon rows of tar-papered barracks encircled by a barbed wire fence with guard towers at intervals, manned by armed soldiers barely visible in the wind-driven dust. It was all so surreal; I wasn’t sure what to make of it.

The wind howled all that night and the dust crept in through the cracks of our unfinished barrack room, but by daybreak all was eerily quiet. I stepped outside as if awakening from a bad dream. Then I saw it. There on the not too distant horizon to the west stood the mountain for which the camp was named, Heart Mountain in all its glory, with the rising sun reflecting off its distinctive eastern face on this cloudless morning, as if to apologize for the rude “greetings” of the night before. The mountain was majestic.

In the following days I did several sketches of the mountain in its various moods, which often reflected my own moods. It was the only sanity I was experiencing at the time. It was the only reality I could rely on. All else had to be an illusion, and in time would all blow away with the dust storm, and only the mountain would remain—or so it seemed to be telling me.

I tried to convey its message to my parents, who must have been questioning the wisdom of immigrating to this “land of freedom and opportunity” which had turned into twenty-six years of hard labor, insults, humiliation, and finally a concentration camp in the middle of nowhere.

I picture them as newlyweds in the lush green countryside of Japan, a far cry from the desolate, windy plains of Wyoming.

***

The year was 1916 in Takamatsu, a small village in the prefecture of Okayama-ken, Japan. Here the primary occupation, as one would guess, was the tending of rice crops, evidenced by the endless paddies flooding the land between raised dikes, the glistening surfaces reflecting the sun’s rays not unlike the panes of a gigantic window covering the earth as far as the eye could see. Indeed, it would seem the harvest of this humble but dedicated enterprise could feed all the hungry of the world and still have enough for the annual local mochi (cooked and pounded glutinous rice) festival.

But on this day the unfortunate demise of the world’s hungry was the least concern of Hisamitsu Kuromiya. Hisamitsu was twenty-nine, and finally able to meet the baishakunin (matchmaker) who had painstakingly searched family records to find a suitable and willing bride for him, a bride who was graced with the highest form of feminine elegance, poise, character, and charm, as befitted a man of his samurai heritage. After all, hadn’t he shown courage in venturing across the fearsome ocean to America at the young age of nineteen to seek his fortunes on his own terms, and in spite of being the eldest son and therefore heir to the family wealth had he remained in Japan? Hisamitsu was a proud man with profound respect for tradition, but he would never allow tradition to define him. He would never accept rewards he hadn’t earned by his own sweat. Neither would he ever surrender to poverty—to hard times perhaps, which seemed the norm in his young life, but never to poverty. In a sense, Hisamitsu was his own worst enemy. But he would abide by his own high standards, for he was an honorable, if stubborn, man.

Later that same day clouds would gather and the once joyful rice paddies would darken, obediently reflecting the gloom of the skies and becoming ominous bottomless pits ready to devour any unsuspecting soul careless enough to venture too close to the edge of the road. The baishakunin assured him that he had faithfully fulfilled all conditions of their agreement, except one, that the prospective mate be of no higher education than high school. The baishakunin considered it a minor condition, but Hisamitsu found this unacceptable. In America he had already suffered the humiliation of being regarded as of a subhuman race by the general public, a public which he regarded as culturally inferior. He was determined not to be humiliated in his own household by a spouse who would regard herself his intellectual superior. Alas, the girl that the hapless baishakunin had selected did indeed meet all the conditions Hisamitsu had requested and more, but she also had just completed a highly respected college course and had graduated with honors. Out of fear of losing his fees, the baishakunin begged for time to find a suitable replacement, but Hisamitsu had to return to his “important” responsibilities in America (which turned out to be that of a houseboy/gardener on the estate of a wealthy though kindly businessman).

Unbeknownst to the baishakunin, however, there was no need to fret. Even though Hisamitsu was adamant regarding the terms of their agreement and was bitterly disappointed in the agent’s oversight, he had no intention of stiffing the poor soul of his anticipated fees. For Hisamitsu was an honorable man who would pay his debts, even if it meant returning to America empty-handed, and even though it might be another six to eight years before he could muster the funds to resume his search for a bride.

Hisamitsu happened to spot an attractive young woman in the village square and was so intrigued with her apparent innocence and charm he beckoned the baishakunin to check out her background. As fate would have it, Hana Tada was sixteen years old and was expected to enroll in college the following year. She had a brother two years older and a personal handmaid who attended to all her needs. The family was of samurai stock, highly respected in the small village, quite well-to-do, and had no intention of giving up their only daughter to a renegade from America. Somehow through the incessant, desperate pleadings of the baishakunin, and perhaps additional monetary incentives from the baishakunin himself, the reluctant parents relented, much to Hisamitsu’s delight. The sun reappeared for Hisamitsu. But for Hana that day was especially dark and grew darker in the days and years to follow. Little did she suspect her carefree days of laughter and joy had vanished with the sunlight. Womanhood was thrust upon her like a Grim Reaper. But Hisamitsu was not the villain. Hisamitsu was a lonely man seeking a companion who would provide him with a family to share in the richness and promise of America, Land of the Free! Land of Opportunity! Or so he dreamt.

***

The samurai warriors were a product of the feudal era in ancient Japan. They were the defenders of the nobility, from whom they received honors and were encouraged to elevate their skills as an art form. Some samurai pursued a philosophical path of insight and self-discipline in an effort to transcend the mundane limitations of the human condition. The samurai were also protectors of the common populace, the merchants, the craftsmen, the artisans, the educators, the healers, the entertainers, the fisherman, and most of all the farmers who opened their doors to them in times of impending invasion from hostile enemy thugs. It was in the interest of the nobility that the samurai protect the villagers on whom they themselves depended to provide all the services, comforts, necessities, and amusement for their elite lifestyle.

The basic stabilizer for this symbiotic relationship was a social caste system which limited everyone to the preestablished occupational level of the family of birth. Thus, once a farmer, always a farmer; once a samurai, always a samurai. The samurai seemed to enjoy a freedom and privilege few others were allowed. He could become a craftsman or a farmer and who would complain? Could it be the samurai was the Joker in the ancient Japanese cultural deck of cards? In any case, perhaps because of the uniquely superior role of the samurai in the caste system, the hiring of a baishakunin to attest to the purity of a samurai family bloodline became a tradition which was still common practice in 1916, long after the samurai himself became extinct.

And so it was that Hana Tada became the latest victim of this ancient custom which robbed her of the innocence of her childhood and perhaps her dreams of meeting and being courted by one of her own choosing. But, of course, tradition is no one’s fault, while at the same time everyone’s fault. How was a sixteen-year-old girl in 1916 Japan to understand that?

After a hasty but properly elaborate and ritualistic wedding ceremony and reception (where Hana no doubt felt more like a spectator than the main attraction), quick good-byes were exchanged with a few close friends and classmates who also seemed to be in a bit of a daze as events happened so suddenly and unexpectedly. It would take them and Hana’s parents and brother a few days to realize that Hana was leaving them, perhaps forever, and it wasn’t Hana’s fault. Hisamitsu with his new bride would embark for America within the next few days.

***

Hana was amazed at the huge liner moored at the harbor in Yokohama. It seemed incredible that so much steel could float on water. She looked at Hisamitsu for reassurance and received a look of impatience and exasperation. “Of course, it’ll float! Haven’t I crossed the ocean twice without so much as getting wet?”

The first time was when he ventured to America at nineteen, and the second when he traveled back to get Hana. Yet, he had to admit to himself the memory of his own terror when he first saw the vast ocean and almost decided to turn back.

Hana’s apprehensions would soon turn to humiliation and disgust as they carried their handbags down each set of narrow metal steps, down, down deeper into the bowels of the steel monster until they came upon a large open arena with a thousand cots neatly lined up. “Nan-da, shir-do cu-ra-su?” (What, third class?) She openly expressed her shock and dismay and silently thought to herself, “Samurai, indeed!”

In spite of Hana’s apprehensions, the ship did not sink. And though the accommodations were crude, they proved to be less depressing than anticipated. Many of the travelers turned out to be newlywed couples like Hana and Hisamitsu. Others were “picture brides” eager to meet their handsome princes and future husbands in distant America. Among the women, mostly in their late teens or early twenties, there was an air of optimism and anticipation of a new adventure free of the social constraints of Japan. But after a few days of exchanging personal backgrounds, much of which were, no doubt, gross exaggerations or outlandish fabrications tailored to impress new friends, a double sickness overwhelmed many of the women. The twin ailments were seasickness and homesickness. All the gaiety and socializing came to an abrupt end and was replaced with incessant sobbing and moping between frantic dashes to the communal bathroom. The dinner halls were almost empty. Of course, the choppy seas were of no help. But later as the seas calmed down and equilibrium was somewhat restored, the tittering and occasional shrieks of laughter gradually resumed. The ship was not sinking after all, although some had been so miserable that they would not have cared if it did, or perhaps had hoped that they would have to turn back due to some mechanical glitch that made it unwise to continue the long voyage still ahead.

To the delight of the already travel-weary passengers, land was eventually sighted in the far-off haze of the horizon. The exciting news beckoned all to scamper to the deck as the land mass became larger and larger. “Is this America?” many asked hopefully. “No,” was the disappointing reply, “It’s just the halfway point, but we will get to go ashore for a few hours while they replenish the ship’s fuel and our kitchen supplies.”

They entered a calm, safe harbor on the coast of an island that one day would play a critical, historic, and painfully personal role in the life of each passenger. The island was O’ahu, Hawai’i. The harbor was most likely Honolulu Harbor, just south of Pearl Harbor.

Hana firmly gripped Hisamitsu’s hand while her other hand had some difficulty unclenching its hold on the rope handrail. The narrow strip of black water far below the gangplank appeared ominous, much like the rice paddies of Takamatsu on a cloudy day. Yes, like that day that had changed her life forever. With the impatient pushing from behind they finally reached the wooden dock, which seemed surprisingly stable. The way everything was supposed to be, thought Hana.

Suddenly a dark-skinned, heavyset woman threw a flowery, sweet-smelling necklace over Hana’s head. Grinning from plump cheek to plump cheek, she joyously exclaimed “Aloha!”

Hana thought in bewilderment, “Nan-da, aho-da?” (What? Stupid?). Hisamitsu quickly explained to her that it was the traditional Hawaiian welcome, and that the lei was a symbol of friendship. Hana, embarrassed, bowed an apology to the lady and murmured “Arigato gozai masu” (thank you very much) as the crowd rudely pushed her along. They spent most of the afternoon visiting the small shops that were filled with gifts and souvenirs. Hana eagerly bought trinkets for her friends in Japan until Hisamitsu reminded her it would be a long time before she would see them again. What a spoilsport, she thought to herself.

Hana was delighted to discover many of the people there spoke Japanese, and some were recent immigrants from Japan themselves. To her, most of the darker-skinned people seemed friendlier, more open, and had a spontaneity and sincerity about them. They appeared less affluent in their attire, but didn’t seem to care. And even though they held a respectful awe of that which was regarded as traditional or sacred and not to be questioned, they were always eager to pull out all the stops when it happened to involve a luau or other joyful celebration.

On the other hand, the lighter-skinned people seemed more self-contained, aloof, and at times e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Beyond the Betrayal: The Memoir of a World War II Japanese American Draft Resister of Conscience

- Appendix A: “Civil Rights” (editorial)

- Appendix B: “Nisei Servicemen’s Record Remembered” (newspaper column)

- Appendix C: “The Fourth Option” (essay)

- Appendix D: Chronology of WWII and Post-WWII Events and Activities

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

- About the Contributors