![]()

chapter one

Children of the Covenant

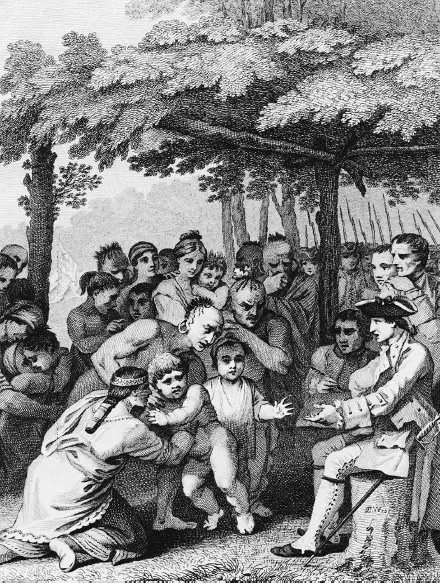

IN THE PREDAWN darkness of February 29, 1704, 48 French soldiers and 200 of their Abenaki, Huron, and Iroquois allies attacked the frontier settlement of Deerfield, Massachusetts. The attackers burned the village, killing 48 of the 300 inhabitants, and took 111 captives. For the next eight weeks the captives were forced to march northward 300 miles through the snow to Canada.1

Among those taken prisoner were seven-year-old Eunice Williams, who lost two brothers in the attack, her clergyman father, her mother, and two surviving siblings. Along the way, Eunice saw at least twenty of her fellow captives executed, including her mother. In Canada the captives were dispersed, some to live with the French, others with the Indians. Eunice, separated from her father and brothers, was taken to a Kahnawake Mohawk mission village, across from Montreal. Two and a half years later, Eunice’s father, the Reverend John Williams, was returned to New England as part of a prisoner exchange. In time, her two siblings were also released. But despite Reverend Williams’ relentless pleas and protracted negotiations with the French and the Mohawks, Eunice refused to leave the Kahnawake. She had converted to Catholicism, forgotten the English language, adopted Indian clothing and hairstyle, and did not want to return to Puritan New England. At the age of sixteen she married a Kahnawake Mohawk named François Xavier Arosen, with whom she would live for half a century until his death. Reverend Williams in his quest to regain his daughter traveled to Canada and saw her, but she refused to go home with him. “She is obstinately resolved to live and dye here, and will not so much as give me one pleasant look,” he wrote in shocked disbelief.2

We do not know why Eunice decided to remain with the Kahnawake, separated from her family and friends, but it seems likely that she found life among the Mohawks more attractive than life among the New England Puritans. The Mohawks were much more indulgent of children, and females, far from being regarded as inferior to males, played an integral role in Mohawk society and politics. Nor was Eunice alone in choosing to remain with her captors. A returned captive named Titus King reported that many young captives decided to become members of their Indian captors’ tribes. “In Six months time they Forsake Father & mother, Forgit thir own Land, Refuess to Speak there own toungue & Seeminly be Holley Swollowed up with the Indians,” he observed.3

Eunice Williams was one of many “white Indians,” English colonists who ran away from home or were taken captive by and elected to stay with Native Americans. Benjamin Franklin described the phenomenon in 1753:

When an Indian Child has been brought up among us, taught our language and habituated to our Customs, yet if he goes to see his relations and makes one Indian Ramble there is no perswading him ever to return. When white persons of either sex have been taken prisoners young by the Indians, and lived awhile among them, tho’ ransomed by their Friends, and treated with all imaginable tenderness to prevail with them to stay among the English, yet in a Short time they become disgusted with our manner of life, and the care and pains that are necessary to support it, and take the first good Opportunity of escaping again into the woods, from whence there is no reclaiming them.

A fourteen-year-old named James McCullough, who lived with the Indians for “eight years, four months, and sixteen days,” had to be brought back in fetters, his legs tied “under his horse’s belly,” his arms tied behind his back. Still, he succeeded in escaping, returning to his Indian family. When children were “redeemed” by the English, they often “cried as if they should die when they were presented to us.” Treated with great kindness by the Indians (the Deerfield children were carried on sleighs and in Indians’ arms or on their backs), and freed of the work obligations imposed on colonial children, many young people found life in captivity preferable to that in New England. Boys hunted, caught fish, and gathered nuts, but were not obliged to do any of the farm chores that colonial boys were required to perform. Girls “planted, tended, and harvested corn,” but had no master “to oversee or drive us, so that we could work as leisurely as we pleased.”4

A Puritan childhood is as alien to twenty-first century Americans as an Indian childhood was to seventeenth-century New Englanders. The Puritans did not sentimentalize childhood; they regarded even newborn infants as potential sinners who contained aggressive and willful impulses that needed to be suppressed. Nor did the Puritans consider childhood a period of relative leisure and playfulness, deserving of indulgence. They considered crawling bestial and play as frivolous and trifling, and self-consciously eliminated the revels and sports that fostered passionate peer relationships in England. In the Puritans’ eyes, children were adults in training who needed to be prepared for salvation and inducted into the world of work as early as possible. Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to misrepresent the Puritans as unusually harsh or controlling parents, who lacked an awareness of children’s special nature. The Puritans were unique in their preoccupation with childrearing, and wrote a disproportionate share of tracts on the subject. As a struggling minority, their survival depended on ensuring that their children retained their values. They were convinced that molding children through proper childrearing and education was the most effective way to shape an orderly and godly society. Their legacy is a fixation on childhood corruption, child nurture, and schooling that remains undiminished in the United States today.5

Benjamin West, “The Indians Delivering Up the English Captives to Colonel Bouquet.” From A Love of His Country, by William Smith (1766). Following France’s defeat in the French and Indian War in 1763, British settlers seized Indian land in violation of treaties with local tribes. An Ottawa chief named Pontiac led an alliance of western Indians in rebellion, killing more than 2,000 colonists and seizing dozens of captives. The British sent Colonel Henry Bouquet and 1,500 troops to subdue the Indians. In return for sparing Indian villages, Bouquet demanded the captives’ return. Benjamin West shows a white child recoiling from a British soldier, seeking refuge in the arms of his adopted Indian parents. Courtesy of the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond.

“Why came you unto this land?” Eleazar Mather asked his congregation in 1671; “was it not mainly with respect to the rising Generation? . . . was it to leave them a rich and wealthy people? was it to leave them Houses, Lands, Livings? Oh, No; but to leave God in the midst of them.” Mather was not alone in claiming that the Puritans had migrated to promote their children’s well-being. Mary Angier declared that her reason for venturing across the Atlantic was “thinking that if her children might get good it would be worthy my journey.” Similarly, Ann Ervington decided to migrate because she feared that “children would curse [their] parents for not getting them to means.” When English Puritans during the 1620s and 1630s contemplated migrating to the New World, their primary motives were to protect their children from moral corruption and to promote their spiritual and economic well-being.6

During the 1620s and 1630s, more than 14,000 English villagers and artisans fled their country to travel to the shores of New England, where they hoped to establish a stable and moral society free from the disruptive demographic and economic transformations that were unsettling England’s social order. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries England experienced mounting inflation, rapid population growth, and a sharp increase in the proportion of children in the population. A 50 percent decline in real wages between 1500 and 1620 prompted a growing number of rural sons and daughters to leave their impoverished families and villages at a very young age to seek apprenticeships or to find employment as live-in servants or independent wage earners. A resulting problem of youthful vagrancy and delinquency led to authorities’ ambitious plans to incarcerate idle and disordered youth in workhouses, conscript them into military service, or transport them overseas. Religious reformers, less troubled by youthful vagrancy and crime, focused on childish mischiefmaking and youthful vice, especially blasphemy, idleness, disobedience, and Sabbath-breaking. This preoccupation with youthful frivolity, religious indifference, and indolence shaped the Puritan outlook, with its emphasis on piety, self-discipline, hard work, and household discipline. When they finally achieved power, the Puritans were eager to suppress England’s traditional youthful culture of Maypole dancing, frolicking, sports, and carnival-like “rituals of misrule” in which young people mocked their elders and expressed their antagonisms toward adult authority ritually and symbolically. The Puritans aggressively proselytized among the young, pressed for an expansion of schooling, and sought to strengthen paternal authority.7

Against this background of disruptive social change, radically conflicting conceptions of the nature of childhood had emerged in Tudor and Stuart England. Anglican traditionalists regarded childhood as a repository of virtues that were rapidly disappearing from English society. For them, the supposed innocence, playfulness, and obedience of children served as a symbolic link with their highly idealized conception of a past “Merrie England” characterized by parish unity, a stable and hierarchical social order, and communal celebrations. At the same time, humanistic educators, who invoked the metaphors of “moist wax” and “fair white wool” to describe children, expressed exceptional optimism about children’s capacity to learn and adapt. For them, children were malleable, and all depended on the nature of their upbringing and education.8

Unlike the early humanists or Anglican traditionalists, who believed that children arrived in the world without personal evil, Puritan sermons and moral tracts portrayed children as riddled by corruption. Even a newborn infant’s soul was tainted with original sin—the human waywardness that caused Adam’s Fall. In the Reverend Benjamin Wadsworth’s words, babies were “filthy, guilty, odious, abominable . . . both by nature and practice.” The Puritan minister Cotton Mather described children’s innate sinfulness even more bluntly: “Are they Young? Yet the Devil has been with them already . . . They go astray as soon as they are born. They no longer step than they stray, they no sooner lisp than they ly.” For Puritans, the moral reformation of childhood offered the key to establishing a godly society.9

The New England Puritans are easily caricatured as an emotionally cold and humorless people who terrorized the young with threats of damnation and hellfire and believed that the chief task of parenthood was to break children’s sinful will. In fact the Puritans were among the first groups to reflect seriously and systematically on children’s nature and the process of childhood development. For a century, their concern with the nurture of the young led them to monopolize writings for and about children, publish many of the earliest works on childrearing and pedagogy, and dominate the field of children’s literature. They were among the first to condemn wetnursing and encourage maternal nursing, and to move beyond literary conceptions that depicted children solely in terms of innocent simplicity or youthful precocity. Perhaps most important, they were the first group to state publicly that entire communities were responsible for children’s moral development and to honor that commitment by requiring communities to establish schools and by criminalizing the physical abuse of children.10

The Puritan preoccupation with childhood was a product of religious beliefs and social circumstances. As members of a reform movement that sought to purify the Church of England and to elevate English morals and manners, the Puritans were convinced that the key to creating a pious society lay in properly rearing, disciplining, and educating a new generation to higher standards of piety. As a small minority group, the Puritans depended on winning the rising generation’s minds and souls in order to prevail in the long term. Migration to New England greatly intensified the Puritans’ fixation on childhood as a critical stage for saving souls. Deeply concerned about the survival of the Puritan experiment in a howling wilderness, fearful that their offspring might revert to savagery, the Puritans considered it essential that children retain certain fundamental values, including an awareness of sin.

In New England, the ready availability of land and uniquely healthy living conditions, the product of clean water and a cool climate, resulted in families that were larger, more stable, and more hierarchical than those in England. In rural England, a typical farm had fewer than forty acres, an insufficient amount to divide among a family’s children. As a result, children customarily left home in their early teens to work as household servants or agricultural laborers in other households. As the Quaker William Penn observed, English parents “do with their children as they do with their souls, put them out at livery for so much a year.” But in New England, distinctive demographic and economic conditions combined with a patriarchal ideology rooted in religion to increase the size of families, intensify paternal controls over the young, and allow parents to keep their children close by. A relatively equal sex ratio and an abundance of land made marriage a virtually universal institution. Because women typically married in their late teens or early twenties, five years earlier than their English counterparts, they bore many more children. On average, women gave birth every two years or so, averaging between seven and nine children, compared with four or five in England. These circumstances allowed the New England Puritans to realize their ideal of a godly family: a patriarchal unit in which a man’s authority over his wife, children, and servants was a part of an interlocking chain of authority extending from God to the lowliest creatures.11

The patriarchal family was the basic building block of Puritan society, and paternal authority received strong reinforcement from the church and community. Within their households, male household heads exercised unusual authority over family members. They were responsible for leading their household in daily prayers and scripture reading, catechizing their children and servants, and teaching household members to read so that they might study the Bible and learn the “good lawes of the Colony.” Childrearing manuals were thus addressed to men, not their wives. They had an obligation to help their sons find a vocation or calling, and a legal right to consent to their children’s marriage. Massachusetts Bay Colony and Connecticut underscored the importance of paternal authority by making it a capital offense for youths sixteen or older to curse or strike their father.12

The Puritans repudiated many traditional English customs that conflicted with a father’s authority, such as godparenthood. The family was a “little commonwealth,” the keystone of the social order and a microcosm of the relationships of superiority and subordination that characterized the larger society. Yet even before the first generation of settlers passed away, there was fear that fathers were failing to properly discipline and educate the young. In 1648 the Massachusetts General Court reprimanded fathers for their negligence and ordered that “all masters of families doe once a week (at the least) catechize their children and servants in the grounds and principles of Religion.” Co...