![]()

Section 1

DEBATING THEORY OF CHANGE IN HE

![]()

1

How Do We Know What We Think We Know – And Are We Right? Five New Questions about Research, Practice and Policy on Widening Access to Higher Education

Neil Harrison

Introduction

One of the challenges that has dogged widening access work in England since its inception has been how we determine what approaches and activities are successful in encouraging people towards higher education – and why. Twenty years on and there is still no consensus about how access work should best be configured, nor how its success can be rigorously evaluated. In this chapter, I will argue that there is an epistemological deficit in the field and that practitioners and policymakers have too often fallen back on simplistic conceptualisations of human behavioural change and how it is evidenced. Evidencing the direct effects of widening access work is, of course, vital for those pursing a theory of change approach.

In a presentation at the Forum for Access and Continuing Education conference in 2012, I posed five questions that I then felt needed answers (Harrison, 2013). These were intended to stimulate epistemological and axiological debate within the sector about the purposes of access work, how effectiveness might be ‘proved’, how resources are targeted, how educational inequalities accumulate and what unintended consequences might arise. The questions themselves were very much of their time, devised at a point when central government funding for widening access had waned, with universities being expected to take up a greater role without a strong binding narrative, but before the Office for Fair Access (now the Office for Students) had grown into its mission.

Looking back, these five original questions could have been expressed more precisely, but I have continued to consider them over the intervening years. Progress has been made on several of them, insofar as that we now have a better understanding through empirical research and theoretical development work, but several remain salient and effectively unanswered.

This chapter will therefore re-use the original conceit to pose five new questions that I believe are relevant to policy, practice and research at the start of the 2020s. 1 I have cheated somewhat, as two of these ‘new’ questions are, in fact, reframings of those I posed nearly a decade ago – albeit with a new focus and (hopefully) more clearly expressed. My intention is that these questions will be generative to those considering how they want their work to shift pathways or narratives for prospective students.

I have structured this chapter around the five questions, outlining what I believe we know about each, why I think it is important they are addressed and what I think are fruitful directions for future thinking. This is necessarily a personal account, based in large part on a series of overlapping studies to which I contributed in the late 2010s – I am hoping the reader will therefore forgive a high incidence of self-citation along the way. My new questions are as follows:

- Why does ‘aspiration-raising’ persist as a conceptual framework?

- Why is there so much ‘deadweight’ in outreach work?

- Why are elite universities collectively unable to widen access?

- Are prospective students reliable witnesses?

- Why do seemingly similar young people end up on different pathways?

I need to cover three definitional points before we move on. Firstly, due to the word count of a short chapter, I focus on access for disadvantaged young people. However, the questions and much of the discussion have a wider applicability – e.g. for mature learners. Secondly, I focus exclusively on England in terms of the policy landscape; again, much will be relevant elsewhere, but space precludes a fuller discussion. Thirdly, I use the term ‘intervention’ extensively to capture the diversity of activities concerned with access, including summer schools, taster days, tutoring/mentoring/coaching, curriculum enhancements and so on.

Question 1: Why Does ‘Aspiration-Raising’ Persist as a Conceptual Framework?

The idea that some people intrinsically want more from their lives than others is deeply ingrained within our hierarchical and meritocratic society. There are normative ideas about what ‘more’ means in this context, usually framed around social standing, income or some other metric of positional advantage. We valourise ‘grafters’ who work hard to employ their talents to better their position – while often sidelining the structural constraints and arbitrary luck that govern both their scope to graft and the outcomes from doing so. Often these discourses are framed around ‘aspirations’ – what do you want from your life?

It was perhaps inevitable, then, that aspirations were co-opted as a conceptual framework for widening access from the earliest days. For example, the foundational policy paper expressed the government's desire to ‘support the broader thrust of raising aspiration and therefore entry to HE’ (Department for Education and Employment, 2000, pp. 7–8), while the 2003 White Paper argued for a focus on families ‘whose aspirations are low’ (Department for Education and Skills, 2003, p. 69). There was vigorous academic critique of this conceptualisation from the outset (e.g. Jones & Thomas, 2005), but it has persisted, with the 2014 national strategy document showcasing programmes designed to ‘raise aspirations’ (Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, 2014, p. 30); it continues to enjoy widespread use in policy and practice discourses (Harrison & Waller, 2017a, 2018; Harrison et al., 2018).

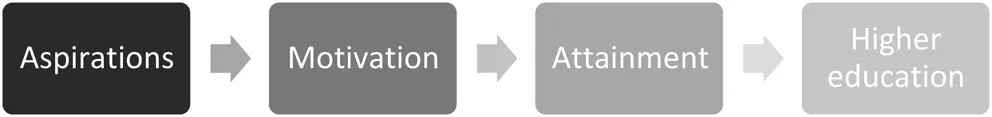

Fig. 1 illustrates how this process is often understood to work and which appears in some form in many policymakers' and practitioners' theories of change about widening access. Raised aspirations, whether for higher education specifically or more generally for a professional career, motivate the young person to work harder at school, leading to improved attainment which affords access to higher education. In this model, aspirations that are grounded in family, community or happiness that are not predicated on higher education are marginalised – or even demonised – as ‘low’.

Fig. 1. A Simplistic Logic Chain for Aspiration-Raising.

I have developed a detailed critique of this elsewhere (Harrison, 2018; Harrison & Waller, 2018), and space only permits a brief overview here. Firstly, there is no evidence that disadvantaged young people have particularly low aspirations (e.g. Archer, DeWitt, & Wong, 2014; Baker et al., 2014; St Clair, Kintrea, & Houston, 2013). If anything, their aspirations are unrealistically high, as many more say they want to go to university than actually do (Croll & Attwood, 2013). Furthermore, a series of evidence reviews commissioned by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation cast specific doubt on the first two links in the theory of change in Fig. 1. They found no reliable links between aspirations, attainment or outcomes for disadvantaged young people, concluding that ‘the widespread emphasis on raising aspirations, in particular, does not seem to be a good foundation for policy or practice’ (Cummings et al., 2012, p. 4). Indeed, Gorard, See, and Davies (2012) argue that attainment most likely drives aspirations and not vice versa.

It is hard to see, therefore, how aspirations can be causally linked with access to higher education when they are not markedly lower among social groups with low participation rates and where there is no strong evidence that aspirations drive attainment; the final link in the theory of change is the only one compellingly evidenced (e.g. Crawford, 2014). There is also an unpleasant flavour of ‘victim blaming’ to the narrative of low aspirations, effectively silencing other explanations grounded in structural inequalities, exclusionary practices or personal choice. Why then has the guiding framework of aspiration-raising persisted until now?

To some extent, this question is rhetorical. Aspiration-raising, like Tinkerbell in Peter Pan, persists because people believe in it. It is ‘truthy’ and fits with the everyday meritocratic beliefs that prevail in English society – that personal success is to be lionised and that it should motivate our actions, even the actions of children. It is hard to step outside this normative environment, even for highly dedicated practitioners who are committed to wider access. The question is included here as a cautionary device, to remind us to interrogate and contest our unthinking assumptions, especially when they are built on shaky social science.

The question also functions as a call to action. One of the reasons that aspiration-raising has persisted for so long is that we lack an alternative conceptual framework. One contender that might bear fruit with ongoing theoretical and empirical work is the concept of ‘expectations’, which is more nuanced and offers richer opportunities than ‘aspirations’. Boxer, Goldstein, DeLorenzo, Savoy, and Mercado (2011) find that expectations about higher education are much lower than aspirations, while Khattab (2015) argues that the two are not closely correlated, making them conceptually and cognitively distinct. Importantly, a young person's expectations about higher education are not only defined by their desire to go (i.e. aspirations), but also objective and subjective evaluations of whether it is likely in their circumstances (Harrison, 2018; Harrison & Waller, 2018). People are not generally motivated by outcomes they considered unlikely, however desirable they may be. Expectations are generative as a lens for decision-making as they widen the focus away from the individual and situate them in a sociocultural context. Expectations are particularly influenced by the adults around the young person – parents, teachers and others – and they become an additional target for intervention.

Question 2: Why Is There So Much ‘Deadweight’ in Outreach Work?

From the relatively early days of widening access, there was a strong concern about how practitioners would identify the ‘right’ young people with whom to engage (e.g. Higher Education Funding Council for England, 2007). Resources were finite and needed to be targeted carefully. However, there was no ready way of making this identification – no off-the-shelf tool to indicate that a young person might access higher education if the situation was right.

One of my original questions focused on the then-prevailing practice of using crude geo-demographic measures (especially POLAR) to identify concentrations of disadvantaged young people. 2 Thankfully this practice has declined substantially over the last decade in the face of mounting evidence that it is flawed and creates new inequalities (Gorard, Boliver, Siddiqui, & Banerjee, 2019; Harrison & McCaig, 2015). In particular, it led to wasted resources in the form of ‘leakage’, whereby relatively advantaged young people received interventions because they lived in what was perceived to be a disadvantaged area, while disadvantaged peers living in advantaged areas were excluded (Harrison & Waller, 2017a). Practitioners increasingly use a more nuanced basket of markers to identify recipients, with much less emphasis on ‘postcode lotteries’.

My new question focuses on a more epistemologically challenging area. The concept of ‘deadweight’ captures the idea that some intervention recipients are already on the pathway towards the desired outcome, even if they (and others) do not know it at the time, creating no change and rendering the intervention worthless. In our specific case, this would mean a disadvantaged young person who would have accessed higher education even without intervention – i.e. a failed theory of change. Deadweight differs from leakage in that the ‘right’ person has been targeted, but that the intervention was unnecessary.

The epistemic challenge here is the difficulty in constructing a valid counterfactual analysis in a complex social space, where there is generally a lengthy time period between interve...