![]()

1

A Woman’s Secret

“What shall I do if I am pregnant by you?”

Woman to a would-be suitor, around 1301

She stood before the Inquisition on that twenty-second day of August, 1320. Although accused of heresy, Béatrice was neither defiant nor humble. She lived life with emotion, devotion, and flair. Mother of four loving and loved daughters, wife to first one and then another member of the lesser gentry, Béatrice lived life, in the words of the a poet of the thirteenth century, as one of the “fair and courteous ladies, who have friends—two or three—besides their wedded lord.”1 She stood before the Inquisition because she was accused of being an Albigensian heretic. This form of heresy is traced back to tenth-century Bulgaria where a group calling themselves the Cathari (“the Pure”) stressed their convictions about a dualistic competition between the god of light and the god or devil of evil. We do not know whether Béatrice was a true “purist” or heretic, or even whether she was found innocent or guilty. The last part of the record is lost, but the first part of the unique Inquisition survives to tell us intimate secrets about Béatrice’s life, her lovers, and her use of birth control drugs.

The bishop from the nearby town of Pamiers was in Béatrice’s village of Montaillou in the Pyrenees mountains near the ridge that sloped downward and southward into Spain. Presiding over the Inquisition that examined Béatrice on suspicion of heresy, Bishop Jacques Fournier was particularly interested in a love affair Béatrice had had with a rogue priest, Pierre Clergue, that had begun about nineteen years earlier. Béatrice had come to the mountain village as a widow after the untimely death of her first husband, Bérenger de Roquefort. Pierre, a priest in the village, had heard that his bastard cousin, Raymond Clergue, known as Pathau, had raped Béatrice while she was married. Undoubtedly he was told that she did not appear resentful, not that it would matter too much, because Pierre considered women as opportunities for conquest. Among those whom he seduced were Alazais Fauré and her sister, Raymonde, Grazide Lizier, and Mengarde Buscailh, just a few of those known to us, and those known probably were in a minority. Many women gave in to his seductive, priestly—albeit heretical—charms. In the eyes of the Church, Pierre Clergue was an Albigensian heretic.

Should a priest seduce women? Yes and no, according to Pierre’s convictions. Sexual activity outside marriage was, he conceded, a sin. But since all other good things in life were as well, it was equal to other activities, therefore acceptable. His distinctly nontheological words were: “One woman’s just like another. The sin is the same, whether she is married or not. Which is as much as to say that there is no sin about it at all.”2 A male’s answer, to be sure.

Bishop Jacques Fournier was interested in the details of how Béatrice was lured into Pierre’s web and entangled in heresy and sin. Those things were defined by the Church, not by the inhabitants of the mountain village. What knowledge of birth control Béatrice brought into this first of her many love affairs is not known, either because she concealed the information or because the Inquisitors failed to probe the depths of her experiences. We possess, however, the testimony of both Béatrice and Pierre before the judicial panel over which Fournier presided. The record of their testimony gives us the rare opportunity to hear from ordinary people (if we may assume Béatrice and Pierre were ordinary).

Without formality or hesitation, Pierre proposed lovemaking when he first met Béatrice as a new widow who came to his church. “What shall I do if I am pregnant by you?” she reacted with neither outrage nor indignity. He responded that he had “a certain herb (quamdam herbam)” that would prevent a woman from conceiving. “What is this herb?” Béatrice queried in apparent or feigned ignorance. She had heard of such herbs; she guessed it was the same one that cowherders put over a pot to keep milk with rennet from curdling. Do not worry about what herb it is, Pierre returned. The important thing was that it worked and he had it in his possession.3 For his own reasons, he did not wish to tell her the herb’s name.

Béatrice gave the Inquisition some details about how the herb was used to prevent pregnancy. This information is preserved in a rare, chance survival of ecclesiastical proceedings in the village of Montaillou. The details are very important, because we learn from the people’s own words what the common folk did. From numerous medical and legal documents we know that people long ago employed contraceptives and early-term abortifacients in order to have control over reproduction. Historians and demographers have assumed that these drugs (for that is what they were) did not work. Before modern times birth control drugs could, at best, be regarded as magical delusions along with exorcism, the evil eye, and other examples of acceptable magic and condemned witchcraft. Much information about these antifertility agents was lost, making the record that Béatrice gave all the more important.

The information she gave to Bishop Fournier and his minions—including a number of scribes who logged the sessions—is unprecedented in recorded history. Among the surprises is that birth control was practiced among common folk, or the nearly common folk. Béatrice was lesser nobility, but she lived her life among the peasants of this and nearby villages. Béatrice’s later lovers, among them a young man when she was much older, were members of the peasant class.

In our age prominent historians (among them Norman Himes, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, Angus McLaren, John Knodel, Etienne van de Walle, A. J. Coale) contend that what practical knowledge there was of effective birth control measures in Béatrice’s time was confined to the beds of the elite, the smart, and the educated.4 Historians have long believed that the upper classes were the first to discover withdrawal before male climax in vaginal intercourse. People in other classes were not sufficiently intelligent to understand it all, so historians believed. Peasants and workers, bakers and candlestick makers, all reproduced like rats in hay until the advent of the modern era, assumed to have begun around 1780. It is widely agreed that the modern era of birth control began about the time of the French Revolution, scarcely more than two hundred years ago.

What was it that Béatrice told the clerical court? Not much, unfortunately for us. But what she did say cautiously is revealing and consequential. Her words are the first direct evidence from hoi polloi that the masses employed birth control devices. It is not that we do not have many sources in medical writings recording prescriptions for both contraceptives and abortifacients. It is not that we do not have demographic evidence that indicates that the people in the many generations before Béatrice were doing something to limit reproduction. Despite the records of birth control drugs and the evidence that people practiced family limitation in meaningful ways, historians have been reluctant to accept the testimony of the historical records.

The appearance of birth control recipes in ancient and medieval Western medical tracts, as well as in Vedic and Chinese works, indicates only that they were known. The texts tell us little about the actual usage of such drugs. The fact that few recipes provide much detail suggests that most of them were orally transmitted. On the other hand, modern scientific and anthropological studies confirm that many of the herbs that appear in the written documents and that were used for birth control were effective.5 If that is so, we must admit that people have long employed chemical means to check fertility. But how many people? Enough to account for modern estimates of earlier population sizes? Enough to explain why, for long periods, some regions (such as Campania and North Africa) had apparent population decline together with economic prosperity, while populations in other regions declined where economic conditions were less vigorous? Why, in other regions, did not economic prosperity and population increase correspond?

Historical demographic studies indicate that premodern peoples may have regulated family size purposely. Population figures for the long period of the Middle Ages are difficult to ascertain. Even so, we know, as did people during the Roman Empire and early Middle Ages, that for long periods the size of families was static or shrinking. Around 200 A.C.E. the population of the Roman Empire (including its Asian and African portions) was around 46 million, 28 million in Europe, and non-Roman Europe had a population of approximately 8 million.6 Another estimate: in the first five centuries A.C.E., the population of Europe is estimated to have declined from 32.8 million to 27.5 million. During this time, it was the population within the bounds of the Roman Empire that declined most, while that of the rest of Europe increased slightly. According to Josiah Russell, a medievalist whose population studies are celebrated, by the year 1000 the population of the same region was 38.5 million, or less than 6 million more than what it had been a millennium before.7

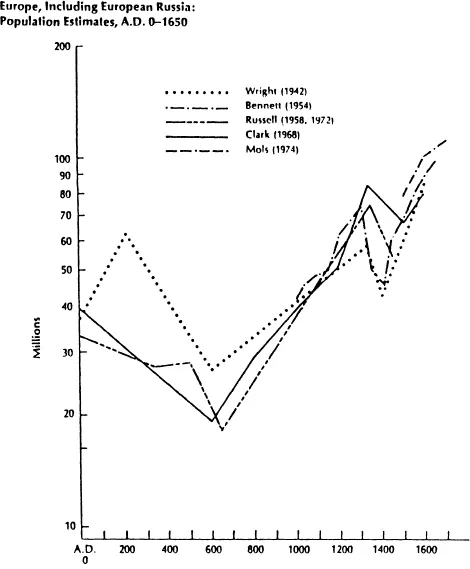

Russell’s projections are compared with those of other scholars in Figure 1. The fundamental point is the basic agreement among scholars about the pattern of population change: decline until the seventh century, a slow recovery followed by a greater advance after or during the tenth century, and, finally, a downturn in the thirteenth with a recovery beginning around 1440.8

Interestingly, much the same pattern of population growth, stagnation, and decrease is estimated to have been played out on a global scale (see Table 1). Historians and demographers have long sought either to explain how premodern peoples engaged in population control or to deny purposeful control at all. Demographers distinguish between birth control and family limitation, the latter being the desire of married couples to have a sufficent number of children. Wars, famine, climate, pestilence, and exposure of children always explained some results, but those calculations were not sufficient to explain the few children born, especially in times of seeming health and prosperity. One example of such a time, when food seldom was a problem and there was relative peace and prosperity, was during the early Roman Empire. In Chapter 6 there is more discussion of demographic data for the modern period; let us look at some specific ancient and medieval data.

In discussing the policy to regulate the size of the ideal city-state, Plato said that there were “many devices available; if too many children are being born, there are measures to check propagation.”9 Through Plato, Socrates identified those devices when he said that “midwives, by means of drugs and incantations, … cause abortions at an early state if they think them desirable.”10 In the second century B.C.E., Polybius complained about the economic viability of Greek cities because, he said, families were limiting their size to one or two children.11 Lawgivers, Aristotle said, should encourage people to reproduce more abundantly if the city is too small or to employ birth control measures if it is too large.12 A Roman writer, Musonius Rufus (ca. 30–101 A.C.E.), was much more specific when he wrote that lawmakers who wanted to increase population size forbade “women to abort… and to use contraceptives.”13 Thus, the combined testimonies of Plato, Aristotle, Polybius, and Musonius indicate that people were employing early-term abortifacients and, just as Pierre presented to Béatrice, contraceptives.

Figure 1. Estimations of Europe’s population (including European Russia), 0 A.C.E.–1650. Citations are to the following references:

Wright, Quincy. 1942. A Study of War, 2 vols. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bennett, M. K. 1954. The World’s Food. New York: Harper and Bros.

Russell, Josiah C. 1958. Late Ancient and Medieval Population. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

—— 1972. “Population in Europe, 500–1500.” In the Fontana Economic History of Europe, ed. Carolo M. Cipolla, 1: 25–70. Glasgow: Collins.

Clark, Colin. 1968. Population Growth and Land Use. New York: St. Martin’s.

Mols, Roger. 1974. “Population in Europe, 1500–1700.” In The Fontana Economic H...