- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

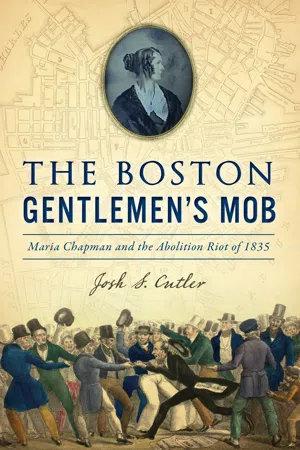

About this book

Violent mobs, racial unrest, attacks on the press--it's the fall of 1835 and the streets of Boston are filled with bankers, merchants and other "gentlemen of property and standing" angered by an emergent antislavery movement. They break up a women's abolitionist meeting and seize newspaper publisher William Lloyd Garrison. While city leaders stand by silently, a small group of women had the courage to speak out. Author Josh Cutler tells the story of the Gentlemen's Mob through the eyes of four key participants: antislavery reformer Maria Chapman; pioneering schoolteacher Susan Paul; the city's establishment mayor, Theodore Lyman; and Wendell Phillips, a young attorney who wanders out of his office to watch the spectacle. The day's events forever changed the course of the abolitionist movement.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Boston Gentlemen's Mob, The by Josh S. Cutler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

1835

Maria Chapman, circa 1850. American Magazine.

MAYOR LYMAN: Ladies, do you wish to see a scene of bloodshed, and confusion? If you do not, go home.

MARIA CHAPMAN: Mr. Lyman, your personal friends are the instigators of this mob; have you ever used your personal influence with them?

MAYOR LYMAN: I know no personal friends; I am merely an official. Indeed, ladies, you must retire. It is dangerous to remain.

MARIA CHAPMAN: If this is the last bulwark of freedom, we may as well die here, as anywhere.

Chapter 1

SUSAN PAUL

The rapid progress of the cause…will, ere long, annihilate the present corrupt state of things and substitute liberty and its concomitant blessings.

BOSTON, OCTOBER 21, 1835—There was no peace officer on site when Susan Paul arrived, only two grinning boys standing by the door who scampered off at her approach. It was shortly after two o’clock on a Wednesday afternoon, and Paul was joined by a handful of women in front of the antislavery office. The clippity-clop sound of hooves and the creak of carriage wheels rumbled past them on Washington Street.

The women expected trouble and cautiously entered the wood-framed building, climbing two flights of stairs to the lecture hall where the annual meeting of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society was to be held. Their meeting had already been postponed once. The original location was rejected by the building’s owner after bowing to pressure from men of “property and standing” who opposed the society’s abolitionist aims.

As Paul made her way upstairs, the passageway to the hall soon began to fill with unwelcome guests who cleaved to the walls and clogged up the way. The men hissed and heckled the women, and a few lobbed orange peel scraps their way. Some stood on the shoulders of others and glared over the partition—though none had yet dared breach the actual lecture hall where the meeting was to be held.

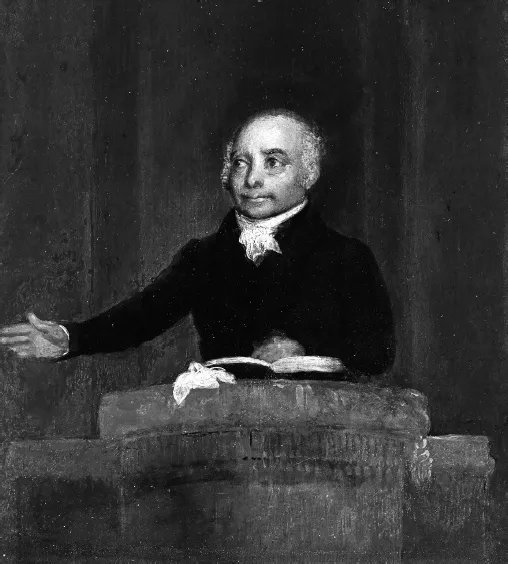

Reverend Thomas Paul. Smithsonian.

While the women greeted one another and settled in their seats, they sent a young boy downstairs to the street entrance to advise any late-arriving members that there was still room inside. Outside, it was an unseasonably warm October day, and inside tempers were also heated. Five more women pushed through and mounted the stairs, but many others turned away, unable—or unwilling—to confront the swarming crowd.

The lecture hall was arranged with plain wooden benches and a raised speaking platform. For Susan Paul, a seamstress and schoolteacher, the scene was reminiscent of a classroom. She took her seat along with her fellow members of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society as they awaited the arrival of their special guest. There were about twenty-five women in the room, most of them white—save Paul and a handful of others, including Lavinia Hilton and Julia Williams.

There are no known images of Susan Paul. Her sister Anne Paul Smith (left) died shortly after giving birth to her daughter, Susan Paul Smith (right), and Paul helped raise her. UNC– Chapel Hill.

As its name announced, the society was avowedly antislavery, but until recently it had only included white women among its members. Despite being well-educated and “warmly loved and respected” by her fellow abolitionists, it was not until outside pressure was applied that Paul was invited to become a member.1

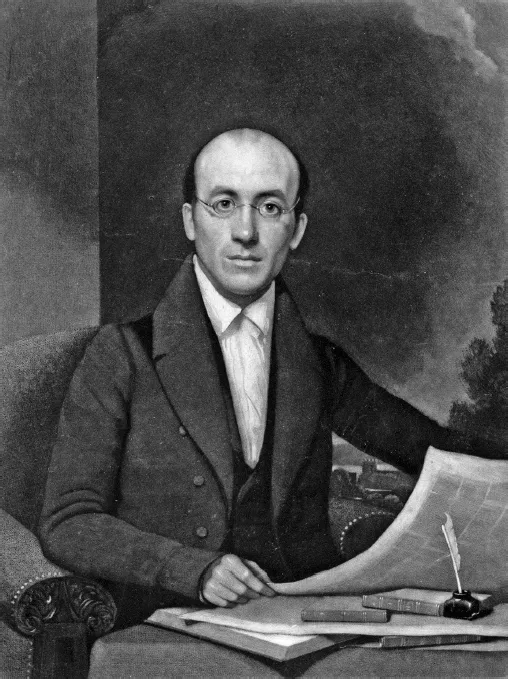

The issue had come to the fore when William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of the abolitionist newspaper the Liberator, was invited to speak shortly after the group’s formation in the fall of 1833. Garrison saw the invitation as an opportunity to teach a lesson and declined. Instead, he urged the all-white women’s society to engage in some self-reflection, declaring it “shocking to my feelings” that the members of an antislavery society would themselves be “slaves of a vulgar and insane prejudice.”2

Garrison’s message was heard “with respect,” and the board agreed to his request. “I am happy to inform you that our decision was on the side of justice, that we resolved to receive our colored friends into our Society, and immediately gave one of them a seat on our Board,” they replied, referring to Susan Paul.3 Thus, the society was now integrated, though equality remained elusive.

William Lloyd Garrison. Boston Public Library.

A PIONEERING FAMILY

Even before her formal admission, Susan Paul was a well-known figure in abolitionist circles. The granddaughter of an enslaved person, she hailed from a prominent and pioneering free Black family with strong ties to Garrison. Indeed, his letter was likely a not-so-subtle attempt to ensure Paul’s selection for the board.

Susan Paul’s grandfather Caesar Nero Paul had been enslaved as a teen and worked as a servant for a prominent New Hampshire merchant. Caesar Paul managed to get himself a rudimentary education and later served during the French and Indian Wars, which may have led to his manumission. By 1790, he lived as a free resident in the town of Stratham, New Hampshire, heading up a household of five. He must have been a strong believer in education because he sent all his sons to public schools near Exeter. Three of them later became Baptist ministers, including Susan’s father, Thomas.

Thomas Paul grew up in New Hampshire and later moved to Boston. As a young man, he hosted religious meetings and led worshippers at Faneuil Hall. He was an accomplished orator—described as “dignified, urbane and attractive” in manner—and his congregation grew over time until the African Baptist Church, the city’s first Black church, was officially organized in 1805 with Thomas Paul as the minister.4

Paul knew that his parishioners needed a permanent home, so he led efforts to build a church on Beacon Hill, which came to be known as the African Meeting House. During his career, Reverend Paul helped spearhead the growing movement of independent Black Baptist churches and traveled abroad to promote abolitionist aims and conduct missionary work. The African Meeting House, sometimes known as “Black Faneuil Hall,” remained a spiritual, cultural and political center in Boston even after his death in 1831.

Susan Paul now carried her family’s social reform mantel. In addition to her antislavery work, she was active with the local temperance society and women’s rights movement. Two years prior, she was elected secretary of the Ladies Temperance Society, which had more than one hundred Black members and had recently helped lead a successful “cold water” campaign to encourage teetotalism.5

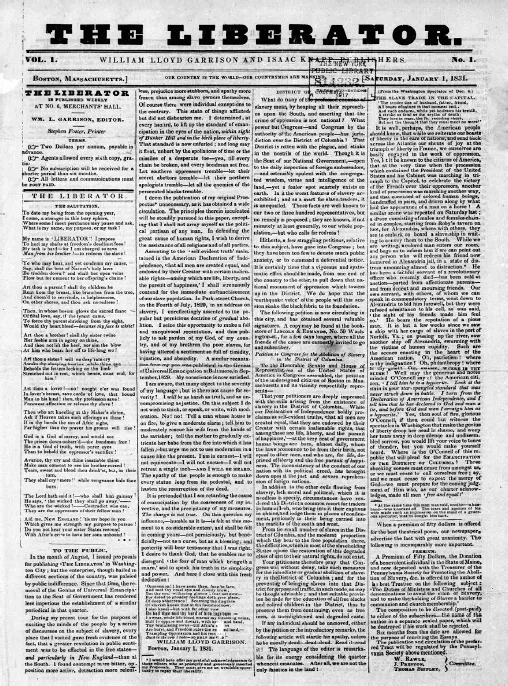

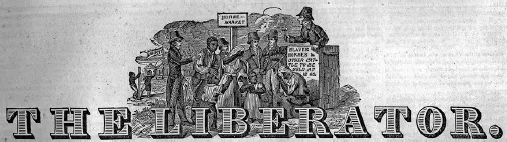

In the first edition of the Liberator, published on January 1, 1831, Garrison made clear that when it came to speaking out against slavery, he would pull no punches: “I will be as harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice. On this subject I do not wish to think, or speak, or write with moderation. No! No!…I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—AND I WILL BE HEARD.” New York Public Library.

Within a few months, Garrison had changed the newspaper’s masthead to the more familiar graphic. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Lately, she poured much of her energy into an innovative juvenile choir program for Black children in the city. The concerts featured a mix of patriotic songs and antislavery hymns sung by Paul’s students, who ranged in age from four up to their early teens. The popular concerts served a dual purpose of highlighting the talents of the young children before mostly white audiences, while spreading the abolitionist message in verse. Paul also taught the students to read music and introduced them to classical composers. Occasionally, she also sang herself, sometimes performing with other antislavery society members, including Lavinia Hilton.

Despite her education, talents and status in the community (“I believe her to be very worthy, industrious and well informed,” said one abolitionist), Paul was not immune to common racial prejudices. A recent trip out of the city for a choir performance before a local antislavery society had driven that point home. When it was time to leave for the event, three stately stagecoaches pulled up in front of Paul and her students, but when the hired drivers saw the complexions of the schoolchildren, they refused to offer them a ride. The men became enraged, shouting out racial epithets and proclaiming, “They would rather have their throats cut from ear to ear” than drive the students.6

For Paul, the episode was distressing but not unexpected. She was able to arrange alternative transportation, and the concert was held as scheduled. The choir was warmly received by a friendly abolitionist crowd, initially unaware of the “uncivil treatment” Paul and her students had overcome to get there. In a letter to Garrison shortly after the event, she shared details about the “cruel prejudice” she’d encountered but also sounded an optimistic note. “The rapid progress of the cause…will, ere long, annihilate the present corrupt state of things and substitute liberty and its concomitant blessings,” she wrote.7

As Susan Paul settled into the wooden bench waiting for the meeting of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society to begin, she may not have realized how much her optimism would be tested on this day.

Chapter 2

MAYOR LYMAN

Behold, ye “Liberators,” “Emancipators,” “Abolitionists,” the fruits of your extravagance and folly, your recklessness, and your criminal plots against the lives of your fellow-men!

Boston mayor Theodore Lyman was hurrying over to his chamber in the Old State House when he noticed a crowd gathering outside the antislavery office, or abolition room, as he called it. It was a warm afternoon, and he could smell the faint aroma of honey from a nearby fruit merchant mingling with pungent tobacco wafting from the reading room that shared space in his building.

The mayor had known for a few days that the women’s antislavery society was hosting a meeting that afternoon, and rumors abounded that British abolitionist leader George Thompson was to be the featured speaker. Knowing that the presence of the contentious abolitionist could inflame local passions, the mayor had dispatched an assistant earlier in the day to see if the rumors were true.

When word came back that Thompson had left the city, the mayor breathed a sigh of relief. Under the circumstances, “no serious disturbance of the peace was to be feared,” though he still took the precaution of having a few constables assembled.8

But now—Thompson or not—it appeared that trouble was brewing, so Mayor Lyman asked the city marshal to walk over and investigate. “I was soon informed that the crowd was increasing very rapidly, and the society could not proceed in their business,” he recalled, and he decided to march over to the antislavery office to judge for himself.9 There was reason to be concerned.

“A CONSUMMATE GENTLEMAN”

Mayor Theodore Lyman, age forty-three and just shy of six feet tall, was a prominent figure in the city. Described as a “consummate gentleman,” the handsome and well-dressed Lyman was first elected mayor two years earlier. His public persona could come across as formal and austere, but friends found him to be generous and warm-hearted. One prominent resident later said of Lyman that he was a man of “unusual grace of bearing and manly beauty.” Another described him as “a model soldier, an admirable magistrate,…and a citizen of great public spirit.”10

Mayor Theodore Lyman, circa 1820. City of Boston Archives.

Lyman was a Latin and French scholar who, as a young man, studied at Exeter and Harvard and later in Europe. He authored several books and served as an officer in the Boston militia. His father, Theodore Lyman Sr., was a prosperous ship merchant who earned wealth trading furs and other goods with China.

Lyman’s politics belied his ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Part I. 1835

- Part II. 1855

- Epilogue

- A Note on Sources

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- About the Author