- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

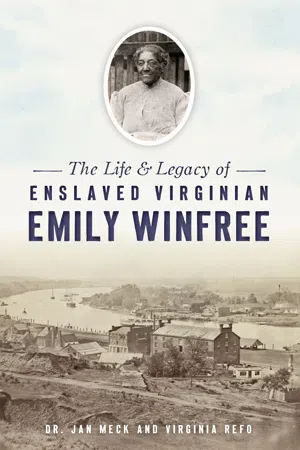

Life & Legacy of Enslaved Virginian Emily Winfree, The

About this book

Left destitute after the Civil War by the death of David Winfree, her former master and the father of her children, Emily Winfree underwent unimaginable hardships to keep her family together. Living with them in the tiny cottage he had given her, she worked menial jobs to make ends meet until the children were old enough to contribute. Her sacrifices enabled the successes of many of her descendants. Authors Jan Meck and Virginia Refo tell the true story of this remarkable African American woman who lived through enslavement, war, Reconstruction and Jim Crow in Central Virginia. The book is enriched with copies of many original documents, as well as personal recollections from a great-granddaughter of Emily's. The story concludes with pictures and biographies of some of her descendants.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Life & Legacy of Enslaved Virginian Emily Winfree, The by Dr. Jan Meck,Virginia Refo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

SIX CURIOUS CHILDREN

All six children were scrambling for the best position. “Get off my foot. You’re squishing me,” squeaked Emily Grace, the youngest. Though petite, she was fearless and scrappy, always right in the thick of things. Stephen scraped her off the floor and plopped her on his shoulders. “Stop squirming or you’ll fall.” “Shhh, if you all don’t shut up and be still, nobody will hear anything,” whispered Walter. Mae immediately declared, “You said shut up! I’m telling Mama! You’re gonna get it.” All this wrangling arose from their determination to hear what the adults were saying on the other side of that thick oaken door. Walter’s warning was prophetic, shut up notwithstanding. Without warning, the door flew open and all six children went tumbling into the room, landing in a noisy, tangled knot of arms and legs, the adults glaring at them. “What on God’s green earth are you children doing?” scolded their mother. “We have told you and told you; when we close that door, we are discussing a topic that is not for the ears of children, especially such disobedient ones. Now, I believe you all have chores to do, and I’m betting you haven’t finished them. So get to it.” As usual, the inquisitive Jones children had been foiled. It was useless to argue, because Mama’s word was law. Dejected, they trudged away to their chores as Grandma “Moosh” watched in silence. She never liked to see her babies in trouble.

“What could be the big secret?” wondered Cornelia. “We know they were only talking about Great-grandma Emily and Great-grandpa David, but they passed away ages ago. What secret would matter after all this time?” “I don’t know, but one day I’ll figure out how to listen in,” said Stephen. Little did the children know that when the secrets about Emily and David were finally revealed to them, four-year-old Emily Grace would be the only one of the six siblings who had not gone to heaven. These six children were Stephen, Mary Lydia (Mae), Cornelia, John Robert, Walter Douglas Jr. and Emily Grace Jones. We shall hear more about them later.

This scene might have unfolded in the home of Mr. and Mrs. Jones (Walter Douglas Jones and Mary Elizabeth Walker Jones), an African American family who lived at 814 West Marshall Street in Richmond, Virginia, in the prosperous African American community of Jackson Ward. Their street was named for John Marshall, the famous chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, whose house (which had become a museum) was just a few blocks away. Jackson Ward was a gerrymandered district that was created in 1871 to concentrate the majority of African American voters in Richmond into one voting district. Although handicapped by Jim Crow laws and policies, prominent leaders such as entrepreneur Maggie Walker, newspaper editor John Mitchell, architect Charles Russell and others helped Jackson Ward become one of the most important African American residential and business districts in the nation. It was a thriving, self-sufficient community that was called the “Harlem of the South” and the “Black Wall Street.” Jackson Ward had its own African American–owned banks, architects, physicians, dentists, lawyers, shops, churches, insurance companies, restaurants, funeral homes, pharmacies, retail stores and entertainment venues. The Hippodrome Theater, opened in 1914, was known nationwide, and such luminaries as Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole, Ray Charles, Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington performed there. Jackson Ward was also a center of the jazz scene. One local group, Roy Johnson’s Happy Pals, became nationally famous. They played at the Savoy Ballroom in New York and once beat out Duke Ellington in a jazz contest in New York City. Residents could find plenty of wholesome entertainment every Saturday night on Second Street, known as the Deuce.

Tragically, in the 1950s, the white establishment cut Jackson Ward in half by routing construction of I-95 right through it and later destroyed the eastern part to build the Richmond Coliseum and expand the Medical College of Virginia. The residents were moved out of Jackson Ward. Public housing projects were built. Emily Winfree’s great-granddaughter told us of how she went to her old house to try to rescue family papers before the house was torn down. Today, Jackson Ward is a shell of its former self, but when the previous scene occurred, it was thriving.

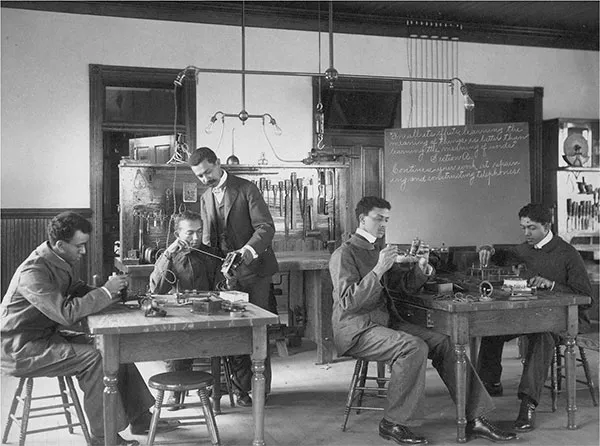

The Jones family was respected in the community, active in civic affairs and leaders in Ebenezer Baptist Church. Mr. Jones was the grandson of the founder of the church. He was a mechanic (trained at Hampton Institute) and had a shop in the backyard. Mrs. Jones was a teacher in Richmond. The family was close. Growing up in Jim Crow Richmond, they had to be. Also, with only two and a half bedrooms and one bath, closeness was a given—privacy a hopeless fantasy. The year was about 1930; Emily Grace was four.

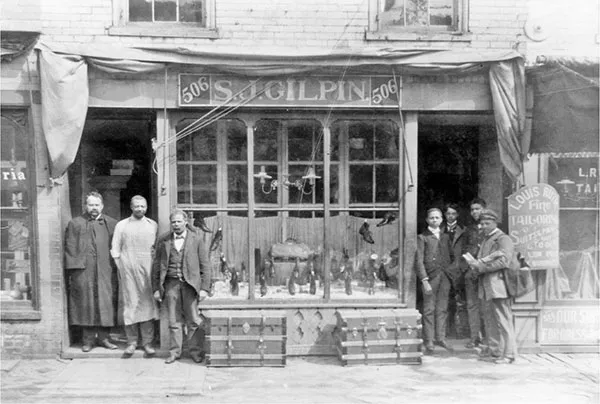

The shoe store of St. James Gilpin on Broad Street in Richmond, circa 1899. His daughter Zenobia Gilpin became a prominent physician in Richmond. Library of Congress.

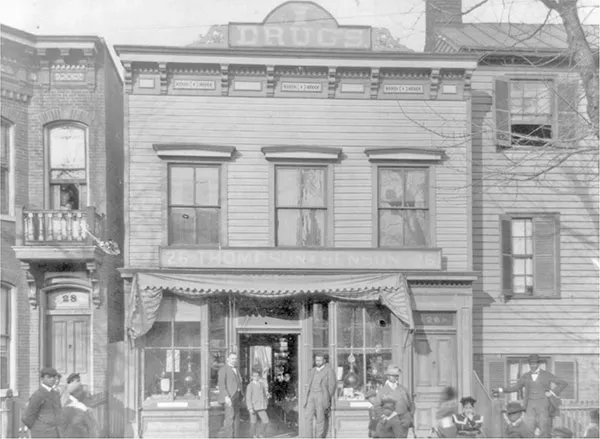

Prosperous Thompson and Benson Pharmacy on Leigh Street in Jackson Ward, circa 1899. Library of Congress.

Young men learning to assemble telephones at Hampton Institute, formerly Hampton Normal, now Hampton University. Library of Congress.

Young women in cooking class at Hampton Institute. Library of Congress.

Grandma “Moosh,” Mrs. Jones’s mother, lived with them. Her name was really Maria (pronounced with a long i) Winfree Walker, but Emily Grace called her Moosh, so Grandma Moosh she was, much beloved by all six children. She was their constant companion while the parents worked, as well as their direct link to their great-grandparents. The Jones children frequently tried to pry information about David, their mysterious great-grandfather, from her. Once in a while, they would get a little tidbit. They were told that he was very fond of their great-grandmother Emily. They heard that he had bought her a house and a farm, but they weren’t sure if that was true. I asked Emily Grace if she knew if David and Emily had ever married, and she told me that was what was being discussed when they got sent out of the room. What they did not know was that their great-grandfather had owned their great-grandmother and their beloved grandmother. Maybe they also didn’t know he was white.

So who was Maria Winfree Walker, Grandma Moosh? Let us introduce you.

Chapter 2

MARIA WINFREE WALKER

A CHILD IS BORN

In her cramped, stuffy quarters in the attic of the big house, eighteen-year-old Emily’s labor pains had grown to a crescendo. The contractions had started off easy, but now, after six hours, they were agonizing. She was trying to muffle her sobs with the sheet so as to not make too much noise in her pain. Her mother was at her side. The midwife had orchestrated everything: hot water, towels, scissors, string—everything was at the ready. After nine long months, and just after midnight, a new baby girl made her appearance. Her skin was much lighter than her mother’s, but this didn’t surprise anyone in the room. Wailing as she confronted the world in which her life would unfold, the baby was no longer protected in the warm, safe womb of her mother. She seemed to intuit that she had emerged into a harsh environment. As Emily took her in her arms, the wonderment of a mother’s love for her child was overshadowed by the stark reality of their situation. For Emily had no husband—could have no husband. She had no legal right to her child, who, on the instant of her birth, was enslaved by the same man who enslaved Emily and her whole family. Her baby could be taken from her at that moment or at any moment henceforth. Her daughter could not marry; would not be educated; could be beaten, raped, sold and even murdered with impunity. Still, Emily was resolved. She made a vow to do anything, sacrifice anything to protect her. She named her daughter Maria. The year was 1856.

“GRANDMA MOOSH”

We had the privilege of hearing about that baby girl, Grandma Moosh, 162 years later from her granddaughter Emily Grace Jones Jefferson, who shared with us her recollections of her beloved grandmother. You see, Emily Grace was the youngest of the six Jones children. Theirs was a very busy and crowded household. Both parents worked very hard to keep food on the table. At times, when other family members had troubles, they would come live with the family as well. Being the smallest, Emily sometimes got lost in the shuffle, but her grandmother was her refuge. She always took the extra time with her. Emily Grace’s earliest memory was falling off to sleep at night, safely nestled in her grandmother’s warm lap and enfolded in her arms. There they were, in the quiet of the slumbering house, gently rocking until the child was fast asleep and still there when the sun welcomed the next morning. “I would fall asleep in her arms, and in the morning I would still be there. She would have sat up all night so I could sleep.” When she was a little older, Emily Grace slept in the bed with Grandma Moosh. When I asked Emily Grace how to spell Moosh, she said, “I don’t know. I had a lisp as a child, and that was how I said her name. Everybody else tried to cure me of the lisp, but Grandma Moosh just told me not to worry because I would grow out of it.” She admits that her grandma spoiled her terribly. Although discipline was strict in the Jones household, it was different for Emily Grace. Moosh told her she would never let her be whipped because her name was Emily, after Moosh’s beloved mother.

Maria sometimes told the Jones children stories about her mother, like how she was the cook at the Possum Lodge. The children laughed because that was such a silly name. She told them it was called the Possum Lodge because, after the war, times were so hard that they couldn’t afford a turkey for Thanksgiving, so they had to cook possums. She told them a little about their great-grandfather too. Maria was ten when he died, so she would have remembered him. She remembered he was very fond of her mother. She knew they had a little house, and she thought he had bought it for them, but she wasn’t sure if that was true. When I informed Emily Grace that it was indeed true because we had found the deed to that house, she was surprised and pleased. The one thing Moosh wouldn’t talk about was the marital status of their great-grandparents. That was always when they were sent from the room.

Emily Grace recounted scenes when their grandma took the children about town on the streetcar. “She was very light, as white as a piece of paper.” This led to some amusement for them on the streetcar. The car ran down Marshall Street and stopped right in front of their house “because the conductor would hear about it if it didn’t. The conductor would step down and help grandma aboard, and she would take a seat in the front, in the ‘whites only’ section.” Then the six children (who were all darker-skinned) would board, file on to the back of the car and take their seats in the “colored section.” When they arrived at their stop, the conductor would assist their grandmother off the car. She would then turn and call out, “Come along, grandchildren,” and they would all come from the back and follow after her. Emily Grace chuckled as she described the white folks with their mouths hanging open in amazement at this white woman with all the little “colored” children.” They were accustomed to seeing an African American “nanny” escorting white children, not the other way around. The children would then follow Moosh on down the street, attending to whatever business they were about.

Grandma Moosh always wore a white blouse and black skirt; in fact, she wore five skirts, all with pockets. Emily Grace was small enough that she could hide beneath the skirts if she needed to feel safe. “She would always carry candy for us in the pocket of one skirt and cookies in another. The pocket of the innermost skirt was where she kept her money. She didn’t trust banks.” When I asked Emily where her grandmother got her money, she said that her other grown children would send it to her. One of Maria’s sons lived in California, and several times he sent her travel money so she could go visit him. Sometimes money for Maria would arrive in the mail in two envelopes, one inside the other. On the outer envelope was the address and postage. On the inner envelope was written, “Don’t take your grandmother’s money.” Although Maria did not trust banks, Emily Grace had a little savings account in Mrs. Maggie Walker’s Penny Savings Bank. She remembers seeing Mrs. Walker out and about on the streets of Jackson Ward.

Maria was very dignified and proper and constantly corrected the children’s English. However, on occasion she was heard to use some very colorful, or rather off-color, language, and when that happened, she told the children not to tell their mother. She is known to have said “bitch” from time to time. Although wise in the ways of the world, Maria never learned to read or write, and she well knew the disadvantages that accompanied her lack of learning. She ingrained in the children the importance of an education and insisted that they all excel in school. All six of them attended college and had successful careers. Actually, truth be told, Emily Grace says that the real reason she wanted to become educated was so that she could earn enough money to buy a house with more than one bathroom; in this, she succeeded. She graduated from Virginia Union University and later became a librarian in the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Another motivation for Emily Grace to do well in school was to be able to assist her grandmother. Maria would often hand her a book and ask her to read it to her or ask her to read her mail to her. She also dictated her letters to young Emily, who would dutifully write them out and address the envelopes for her.

The Jones family was close, and that was important for survival in those times. Emily Grace told us how difficult and even dangerous life was for African Americans in Jim Crow Richmond. She said that the girls could not walk down Broad Street unless one of their brothers was with them because white men would accuse them of being prostitutes. This was very dangerous, as rape of black women was a big problem. “But if you worked for a white family and had on a uniform, that would protect you.” However, working as a domestic servant in a white household was also dangerous for African American girls. It was common knowledge that many of them were violated by the white men in the house, and many fathers would not allow their daughters to take such employment. That is one reason why the Jones family insisted their children get a good education.

Another painful memory was that of shopping. In white-owned department stores, African Americans were sometimes not allowed in the front door; not allowed to try on or return clothing; or required to step aside when a white person came up and wait to be served until all the white customers had been helped. Maggie Walker opened a department store so that people could shop with dignity, but white store owners manipulated her suppliers to stop selling to her, and that forced the store to close.

There is not room here to expound upon all the injustices served up to the African American community. These are only a few inflicted on them during Jim Crow, but they were marked in the mind and worldview of the young girl who still talks about them all these years later. No amount of success in life can erase them. Today, Emily Grace laments the fact that younger generations don’t understand what it was like in Richmond back then. Younger family members often ask her why she would let people talk to her and treat her the way they did. She tells them, “Because I’d be dead if I didn’t.” Those were dangerous times. Many lynchings occurred in Virginia, although not as many as in the Deep South states. In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative of Montgomery, Alabama, counted seventy-six lynchings in Virginia between 1877 and 1950. Emily Grace grew up knowing of the terror around her.

But Grandma Moosh protected her grandchildren from anybody, no matter who it was. “She wasn’t afraid of anything.” She would stride down to the courthouse on Marshall Street, children in tow, and talk to the white judges. They all knew and respected her and would come down off the bench to converse with her, while Emily Grace listened intently, hidden beneath Moosh’s skirts. Sometimes Maria and a judge would engage in general conversation, but her real purpose was to make sure the judges knew all of her grandchildren. She told the judges that her grandchildren were all good children. She told them that if there was ever an incident involving any of her grandchildren, the police were to first call her, and she would come down and take care of it. And that’s just what happened on the rare times there was trouble. This continued even after the children were grown and working. She also would go down and inform the judges when anything untoward happened in the neighborhood and let them know that she expected them to take care of it. She was representing and protecting the children of the entire ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Six Curious Children

- 2. Maria Winfree Walker

- 3. Emily Winfree

- 4. Family Separations

- 5. David Winfree

- 6. David and Emily in Chesterfield County

- 7. David’s Death

- 8. Broken Promises: Lost Hope

- 9. Emily’s Postwar Years

- 10. Sickness Strikes

- 11. The Legacy

- Epilogue

- Appendix I. Deed to House in Manchester

- Appendix II. Deed to Acreage

- Appendix III. Petition to Sell Timber from Acreage and Build House

- Appendix IV. Deed for Sale of Acreage to Woodbury

- Appendix V. Petition by Emily and All Her Children to Pay Off All Deed of Trust Notes but Give Up the Cottage Due to Back Taxes

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Authors