eBook - ePub

Explorations in the Icy North

How Travel Narratives Shaped Arctic Science in the Nineteenth Century

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Explorations in the Icy North

How Travel Narratives Shaped Arctic Science in the Nineteenth Century

About this book

Science in the Arctic changed dramatically over the course of the nineteenth century, when early, scattered attempts in the region to gather knowledge about all aspects of the natural world transitioned to a more unified Arctic science under the First International Polar Year in 1882. The IPY brought together researchers from multiple countries with the aim of undertaking systematic and coordinated experiments and observations in the Arctic and Antarctic. Harsh conditions, intense isolation, and acute danger inevitably impacted the making and communicating of scientific knowledge. At the same time, changes in ideas about what it meant to be an authoritative observer of natural phenomena were linked to tensions in imperial ambitions, national identities, and international collaborations of the IPY. Through a focused study of travel narratives in the British, Danish, Canadian, and American contexts, Nanna Katrine Lüders Kaalund uncovers not only the transnational nature of Arctic exploration, but also how the publication and reception of literature about it shaped an extreme environment, its explorers, and their scientific practices. She reveals how, far beyond the metropole—in the vast area we understand today as the North American and Greenlandic Arctic—explorations and the narratives that followed ultimately influenced the production of field science in the nineteenth century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Explorations in the Icy North by Nanna Katrine Luders Kaalund,Nanna Katrine Lüders Kaalund in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

New Beginnings in the Arctic

The expeditions which have recently been engaged in for discovering a North-west passage, though unsuccessful in their main objective, are generally, and very properly, considered undertakings of great utility. Conducted as such expeditions now are, they cannot fail of procuring many valuable additions to the arts and sciences; whilst the spirit of enterprise kept alive by them, both in officers and seamen, renders them an appropriate service in time of peace, for the employment of a small portion of that navy, which during the war established our right to the uninterrupted navigation of all “the mighty waters.”

— Thomas Merton (pseud.), “Arctic Natural History,” Literary Magnet, 1824

Following the end of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars that took place between 1792 and 1815, there was a significant renewed interest in the Arctic. The possibility of discovering a trading route to the Pacific was a major incentive, but it was not the only motivator. Although geographical discovery was the official primary goal, scientific discoveries were central to the expeditions. This was especially so when faced with a lack of geographical results. The first expeditions organized by the British government following the wars were important in showing what could be accomplished scientifically in the Arctic. We can look to the expeditions’ official orders for the types of science that sponsoring parties such as the British Navy valued. These included requests for experiments on magnetism, the aurora borealis, the figure of the Earth, refraction, ocean currents, mineralogy, zoology, botany, hydrography, ethnology, and the general collection of natural history specimens; all in all, such requests were very vague and very broad. Geography was also considered a science, but geographical discovery and mapping were evaluated separately by organizers and explorers. This vagueness of the official instructions to the expeditions is a clear indication of the difficulties faced by explorers before, during, and following their journey to the Arctic.

This chapter explores this uncertainty through three early nineteenth-century expeditions: the twin 1818 British Arctic voyages in search of the Northwest Passage and the North Pole led by John Ross (1777–1856) and David Buchan (1780–1838), with a focus on Ross; John Franklin’s Coppermine expedition; and the Danish expedition to the east coast of Greenland under William August Graah. In contrast with Ross’s voyage, both Graah’s and Franklin’s expeditions relied heavily on the assistance of trading companies and Indigenous communities, and the trajectories of their projects were shaped by this support. In all three cases the results were wide-ranging and largely dependent on the abilities of the crew, as well as the luck of the expeditions, the environment, and the people they encountered before, during, and after the expeditions. Consequently, there was not always a match between the expeditions’ goals, scientifically and geographically, and what they actually produced.

That is not to say that people such as the second secretary of the Admiralty John Barrow did not play a key role in determining the makeup of the voyages and the career trajectory of the explorers, but there were clear limitations to their control. There was no unified practice of science in the Arctic, and no functioning blueprint for creating a successful expedition. Just as the experiences of the crew and what they were able to achieve were markedly unpredictable, what followed upon their return was also hard to control. As the case of Ross illustrates, the textual strategies employed to navigate the expectations of expeditions were difficult to manage and formed a central part in the quick downfall of his career and public persona. This had to do with the unstable nature of intellectual and cultural authority. Both the variability and perception of the results were shaped by the stylistic choices in the travel narratives, including the construction of the Arctic explorer’s persona. In the early nineteenth century the nature of scientific practices in the Arctic and the publication of travel narratives were shaped by uncertainty and instability. It was not possible for the metropole to determine the results from and reception of the expeditions.

A VOYAGE OF DISCOVERY: THE FIRST BRITISH ARCTIC EXPLORATIONS

During a voyage to the Arctic in 1817, the whaling captain and naturalist William Scoresby (1789–1857) noticed that there was less polar ice than usual. A decrease in polar ice meant an increase in open water, and a potential for reaching areas which had hitherto been impenetrable by ship. Scoresby informed the influential British naturalist Joseph Banks (1743–1820) of this change. He suggested to Banks that it would be an opportune time for the British government to sponsor an expedition—although he warned that the amount of ice might not stay stable for the following season. Scoresby had his own reasons for bringing this to the attention of the government: he wished to lead the suggested expedition. Intrigued by Scoresby’s information, Banks in turn counseled Robert Dundas (1771–1851), also known as Lord Melville, the first lord of the Admiralty, on the possibility and opportunities for discovering a Northwest Passage. Dundas, as well as Barrow, were quick to see the possibilities offered by this apparent change in the Arctic climate, but it was not Scoresby they had in mind to actualize their project.1

Another factor in making the decision to organize the first Arctic expeditions after the wars was the changing geopolitical situation of the early nineteenth century. During the wars British naval science and Arctic explorations had been on hold. In 1812, 113,000 seamen had been funded by the British Parliament, but this fell to 24,000 in 1816. Up to 90 percent of officers were unemployed by 1817, and peacetime meant that this large number of un- and underemployed seamen were keen to secure a post.2 The expansion of the Ordnance Survey provided a key opportunity for employment for these men. Officers trained in scientific surveying were useful in this revival of British Arctic exploration. Even more so, their skills and approach to fieldwork played a big part in shaping efforts to implement the grand geopolitical dreams of establishing authority in a region which seemed to promise a faster route to the Pacific.

Barrow had several motives for supporting Arctic explorations. The economic possibilities from a potentially faster and safer trading route were obvious, but national pride was also a significant factor. The advance of science and the national glory associated with such scientific progress factored heavily in Barrow’s thinking. And in the event the Northwest Passage was not discovered, Barrow hoped that there would be significant scientific discoveries resulting from the expeditions. These could, for example, be utilized to advance knowledge of the British climate to improve agricultural practices. The use of foreign land as a laboratory for the advance of British science has a long history. For example, the historians Richard Grove, Deborah Neill, Nancy Stepan, and Katherine Anderson have shown how British colonialism in the tropics facilitated studies that extrapolated from a specific environment to new evaluations of (British) nature more generally.3 While the primary goal of Barrow’s push for Arctic exploration was geographical, the secondary purpose was scientific. This tension—between the very clear aim of finding a passageway and a more general idea of scientific advancement—mattered greatly at all stages of the Arctic exploration, starting with the choice of vessels and crew.

The people selected to lead the twin 1818 voyages in search of the Northwest Passage and the North Pole were John Ross and David Buchan. Buchan and his second-in-command, Lieutenant John Franklin, had command of the ships HMS Dorothea and HMS Trent. The goal of Buchan’s expedition was to reach the Pacific Ocean through the hypothesized Open Polar Sea and the North Pole. Ross’s expedition sought to reach the Pacific Ocean by going through Baffin Bay and Lancaster Sound. Ross’s second-in-command was Lieutenant William Parry (1790–1855), and together they had command of the HMS Isabella and HMS Alexander. As the first voyages to the Arctic after the Napoleonic Wars, Ross’s and Buchan’s expeditions were central in establishing British dominance in the Arctic region and in showing what could be accomplished with future ventures to the Arctic. The problem was that neither of these expeditions were particularly successful, if success was to be judged from their goal of finding a Northwest Passage.

Ross accounted for his expedition in A Voyage of Discovery, Made under the Orders of the Admiralty, in His Majesty’s Ships Isabella and Alexander, for the Purpose of Exploring Baffin’s Bay, and Inquiring into the Probability of a North-West Passage (1819).4 Ross’s narrative was influential in shaping perceptions of the Artic and what did, and did not, constitute an authoritative Arctic explorer. As Ross would learn the hard way, the techniques used to establish an authoritative voice shaped the tone of the narrative. This in turn affected the description of the Arctic, the science carried out there, and the nature of the Arctic explorer. Originally the intention was to publish an official account, sanctioned by the head of the British Navy, of Ross’s and Buchan’s voyages. In both cases, this was decided against, in part because the expeditions had come nowhere close to fulfilling their geographical goals. Ross published his, now unofficial account of the expedition in 1819. Buchan, on the other hand, did not publish an account of his attempt to reach the North Pole, due to what he perceived as their lack of results. A full narrative of Buchan’s voyage was not made until Frederich William Beechey (1796–1856), a lieutenant on the expedition, published A Voyage of Discovery towards the North Pole: Performed in His Majesty’s Ships Dorothea and Trent, under the Command of Captain David Buchan, R.N.; 1818; to which Is Added, a Summary of All the Early Attempts to Reach the Pacific by Way of the Pole in 1843.5

As outlined in the official instructions to the expeditions, the primary focus of Ross and Buchan’s voyages was geographical. The secondary focus was scientific, and the importance placed on this aspect is evident in the number of valuable scientific instruments and books on board the ships, as well as the detailed requests for a wide range of scientific results. In addition to playing a central role in deciding which officers were part of the Arctic expeditions, Barrow also determined which scientific instruments the Admiralty would purchase for them. It is for reasons such as this that Barrow’s biographer Christopher Lloyd has described him as a figure who always appeared in the background directing the course of naval policy. Ross’s conflicts with Barrow started early on, as Barrow denied his request for an additional timekeeper to bring on board the Isabella.6 In the end Ross purchased the timekeeper himself. Barrow’s influence did not end with the expedition, but extended through the post-expedition narration of the voyages. John Murray was an official publishing house for the Admiralty, and it produced a large part of the travel accounts from expeditions to the Arctic (and Africa) in the first half of the nineteenth century. Barrow functioned both as a preprint reader and post-publication reviewer for Murray. In this way he influenced both the physical makeup of the expeditions, their orders and instructions, and the portrayal of the expeditions and the Arctic upon the conclusion of each expedition.7

The key scientific areas of interest as outlined in their official instructions were to examine the variation and inclination of the magnetic needle, the intensity and variation of the magnetic force, the temperature of the air and of the surface of the sea, the dip of the horizon compared over fields of ice and open horizon, refraction of objects over ice, the character of the tides and currents, the depth and soundings of the sea, and the sea bottom. In addition to observations linked to meteorology, they were also to collect and preserve animal, mineral and vegetable specimens, and make drawings and descriptions of those they could not preserve and store on board the ships. The vagueness of this particular part of the official instructions illustrates the extent to which they were venturing into the unknown. It was impossible to know what could be expected and what could be discovered when (or rather, if) they reached their destinations. For example, the hope was that Buchan’s expedition would reach the North Pole and there be able to make “the observations which it is to be expected your interesting and unexampled situation may furnish you with.”8 In Ross’s official instructions, the Admiralty lamented their inability to provide detailed guidance with regard to route and time frame for the voyage, as the land in the region was unknown. Therefore, the instructions specified that they relied on Ross’s skill and zeal for the safe fulfillment of the objectives of the voyage.

It is worth reiterating that while the primary goal of their expeditions were geographical, the official secondary purpose was scientific advancement. Many of the instruments the ships carried were related to one of the key research areas of Arctic explorations: magnetism. Terrestrial magnetism was a research area full of unknowns, one that greatly affected the practical aspects of seafaring. Knowing where you were was a central part of exploration. Since the time of the early astronomers, it had been possible to measure latitude with a fair amount of accuracy. Determining longitude, however, was more problematic. Whereas latitude, the position on a north–south axis, could be determined with the aid of stars or the sun, this was not enough to determine longitude, the position on an east–west axis. A fixed reference point of known longitude was needed, from which the ship’s position at sea could be determined by the difference in time between it and the known position. Many European countries were interested in solving this issue. The British government established the Board of Longitude in 1714, with a prize for discovering a way to reliably determine longitude at sea. The Longitude Prize was awarded to John Harrison in 1773 for the design of a chronometer, a device that could keep time for months and was not easily affected by the conditions at sea.9

Another tool for navigation was the dip circle or dipping needle. The dip of the needle was recorded as part of studying geomagnetism. The needle moved in a vertical plane, to measure vertical magnetic inclination. At the Magnetic North Pole the needle in the instrument would point downward, as the magnetic field became more vertical. If Buchan’s expedition had discovered the Magnetic North Pole, they would have measured a dip of 90°. Buchan’s expedition came nowhere near either the Geographic or Magnetic North Pole, but both Buchan’s and Ross’s expeditions carried with them several dipping needles, as well as chronometers and magnetic compasses. The Isabella, Ross’s ship, contained seven chronometers, three of which were the property of the British government, with four privately owned. (The Alexander had three government chronometers.) The Isabella further brought with it four dipping needles and seven compasses. They included multiple versions of the same type of instrument from different manufacturers to maximize the data they could produce and ensure their reliability.

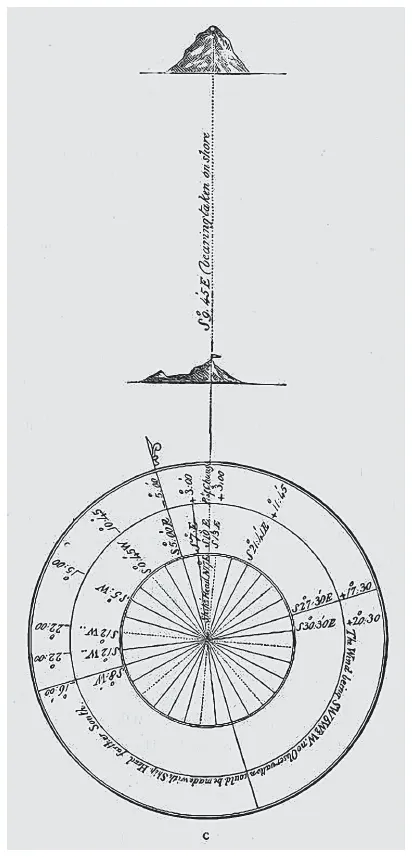

FIGURE 1.1. Illustration showing the method by which John Ross’s expedition took transit bearings using a mark on the shore as a set reference point. Source: John Ross, A Voyage of Discovery, 1819, xvii. Courtesy of the Scott Polar Research Institute.

In order to obtain the true variation by reference to a fixed spot on land, the expedition placed a flag on a high point from which they used a compass to ascertain the bearing of a fixed spot on a mountain. The ship was steered to bring the flag and the fixed spot in one line, which allowed them to take the transit bearings. This process provided a reference for navigation with the compass, to add or subtract the degrees and minutes from the variation observed. Experiments and measurements such as these were included in the narrative, with tables and illustrations. We know from Ross’s narrative and private notebook that they typically took the same measurements multiple times with different instruments to determine if any of the instruments provided outlying data. An average could then be calculated from multiple experiments. For example, during a quiet stretch of days at sea, Ross’s expedition party made several observations with their instruments and found that Jennings’s insulated compass was the median between them. One of the proposed disturbances was the iron in the ships. Because of the difference in results, Ross noted the name of each instrument and the person who had performed the observations in his notebook. By making multiple experiments with several instruments and from different points, Ross attempted to maximize the impact and accuracy of his scientific results. It was a way to eliminate mistakes, something that was later repeated in variation in the methodology of the First IPY as discussed in Chapter 4. The appendix of the published narrative also contained a “Report on Compasses, Instruments,” and “Reports on Various Instruments Supplied to His Majesty’s Ships Isabella and Alexander” that evaluated them. It provided a way for the instrument manufacturers to test if their devices were stable and accurate. In this way Arctic voyages functioned as a practical test spaces. The measurements made during Arctic explorations were key evidentiary sources for many research fields, even long after the voyage had taken place. Consequently, explorers faced multifaceted challenges when they wanted to c...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. New Beginnings in the Arctic

- 2. Financial Opportunities in the Arctic

- 3. The Lost Franklin Expedition and New Opportunities for Arctic Exploration

- 4. From Science in the Arctic to Arctic Science

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index