- 436 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was the outstanding public event of the Victorian era. Housed in Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace, it presented a vast array of objects, technologies and works of art from around the world. The sources in this edition provide a depth of context for study into the Exhibition.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Great Exhibition Vol 3 by Geoffrey Cantor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

IV. GUIDES TO THE EXHIBITION AND OTHER MATERIAL ADDRESSED TO VISITORS

DOI: 10.4324/9781003112891-1

This section opens with an extract from one of the guides to London that was issued before the Exhibition opened. London as It Is To-Day: Where to Go, and What to See, during the Great Exhibition portrayed London as the most exciting and dynamic place on earth and thereby set the scene for visitors travelling to the metropolis in the summer of 1851. Many of those who came would not have previously visited London; as several publishers appreciated, they would take the opportunity of visiting not just the Exhibition but also other tourist sites, including both traditional ones, like the newly rebuilt Palace of Westminster, St Paul’s Cathedral and the Inns of Court, and entertainments, such as the panorama of the Nile (at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly) and Wyld’s ‘Great Model of the Globe’ in Leicester Square, that had been mounted specifically for the expected influx of tourists in 1851. Guides like London as It Is To-Day, which included a street plan, were packed with information about the history of London, the major tourist sites, the railway termini, the principal hotels and the best shops and exhibitions, including the momentous exhibition in Hyde Park.

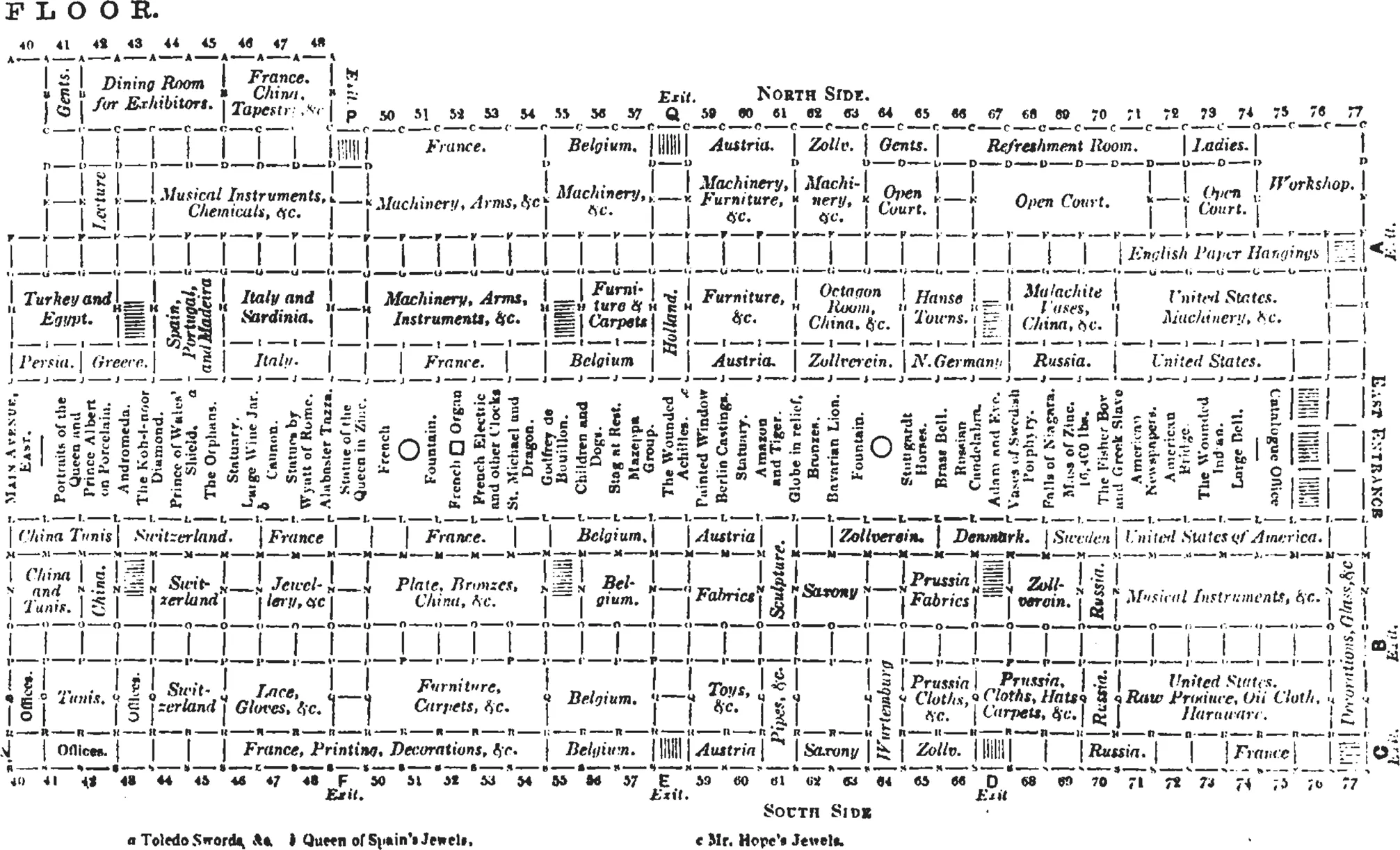

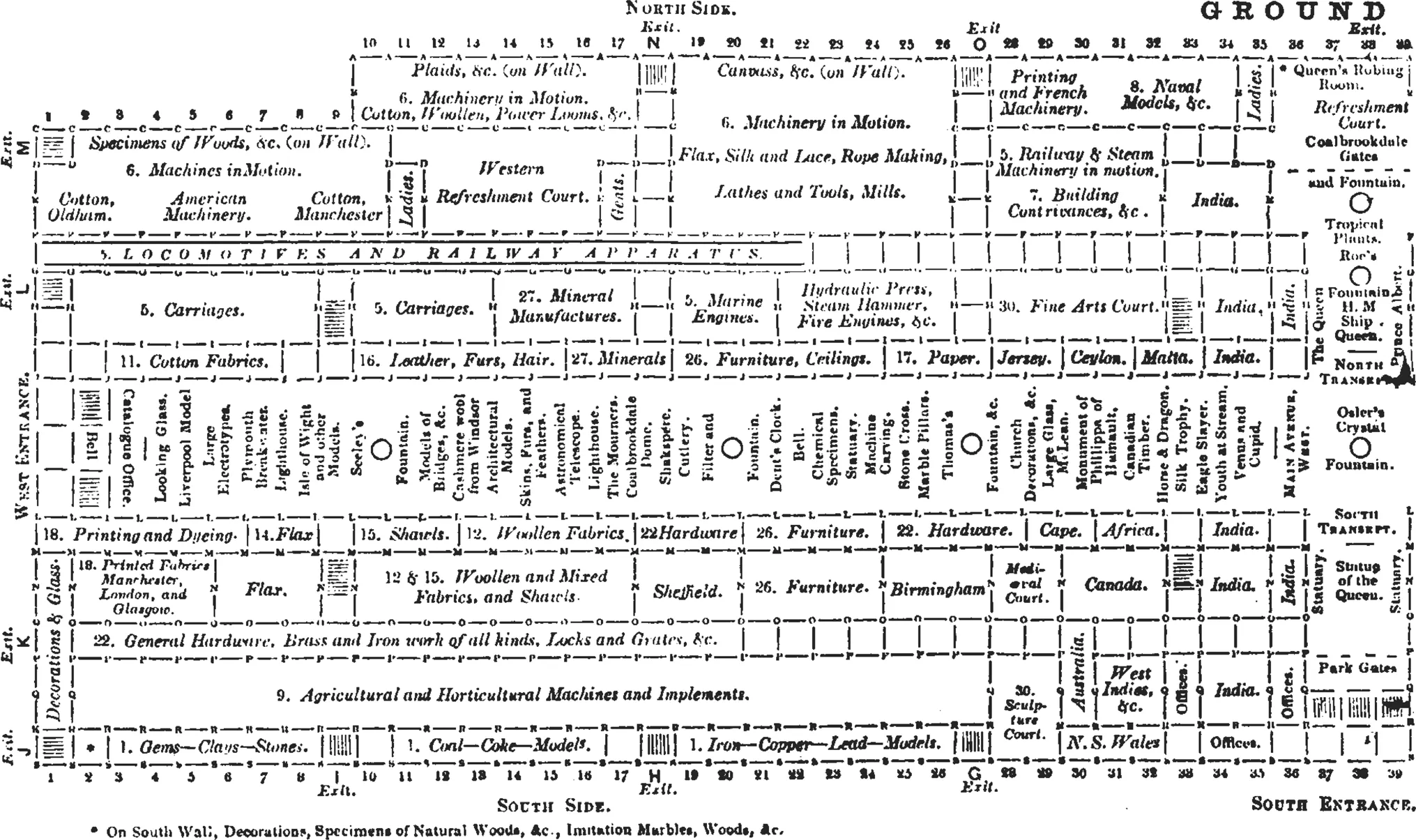

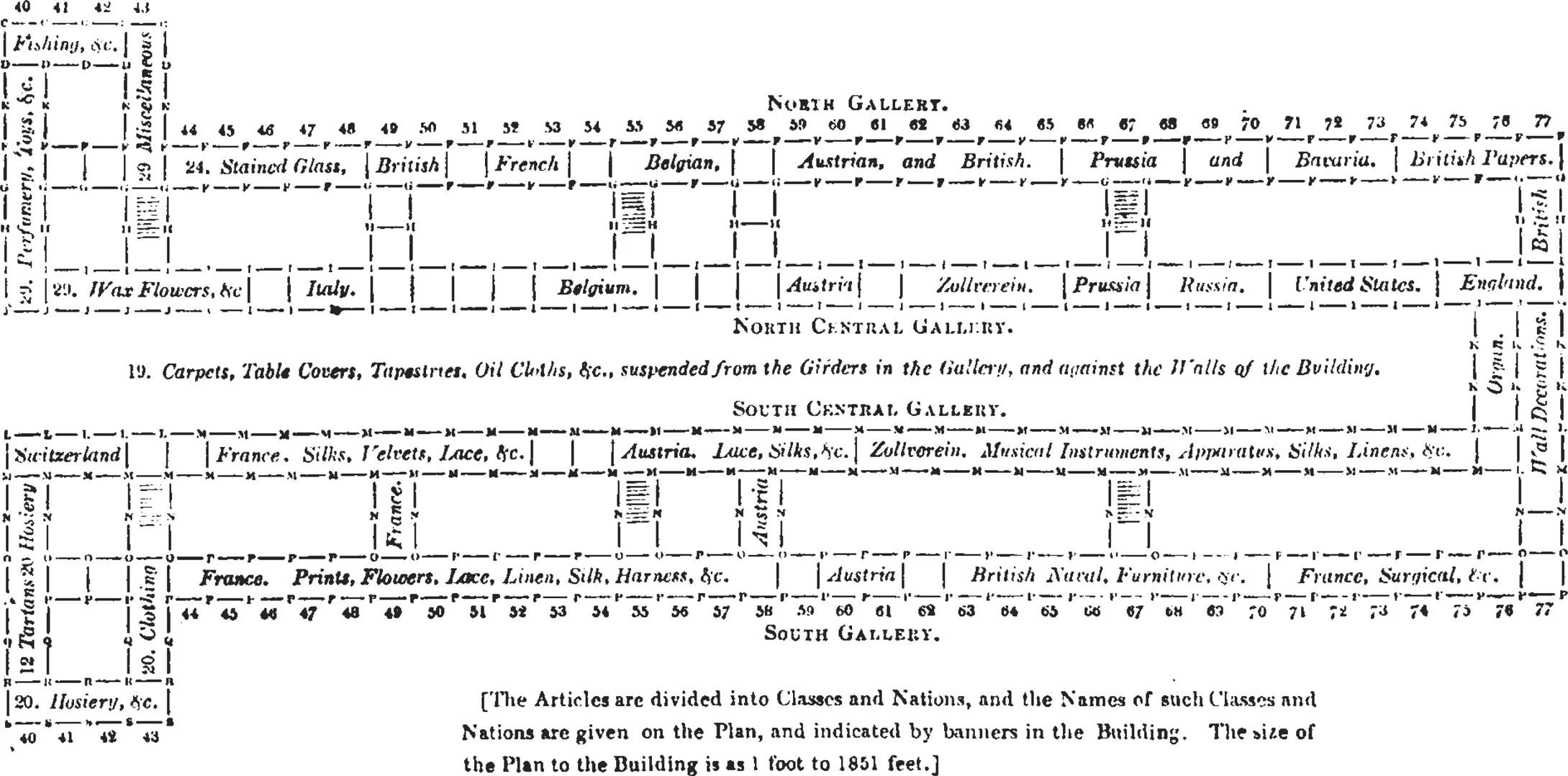

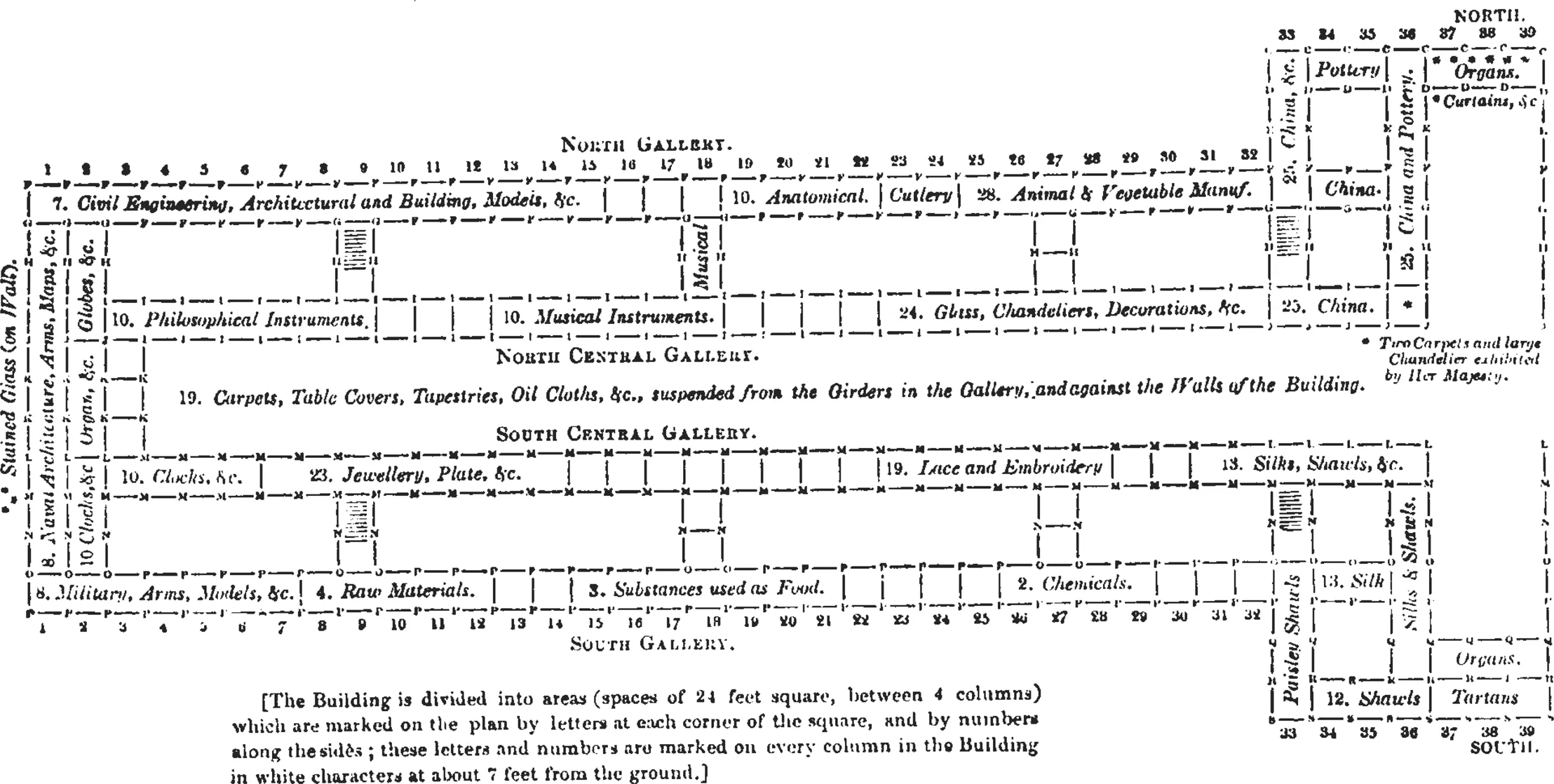

As the General Introduction has emphasized, the Exhibition was so extensive that serious visitors required guidance in some form. Thus escorts, some of whom spoke foreign languages, offered their services for a fee.1 However, most visitors were self-directing, having obtained the assistance of one of the many published guides, which contained plans of both the main floor and gallery of the Crystal Palace. ODIC, originally issued in five parts throughout the course of the Exhibition, was of little use to the visitor owing to its bulk and expense and, until almost the closing date, also its incompleteness. It was subjected to much criti-cism; for example, a commentator in the Mechanics’ Magazine stated that ODIC was ‘so enormously dear that few can afford to buy it, and so wretchedly ill-done (as a whole) that it is not worth buying’.2 By contrast with ODIC, 300,000 copies of the Official Catalogue were sold during the course of the Exhibition at either 1s. 3d. or 1s. if purchased at the Exhibition. The French and German editions retailed at 2s. 6d. The Official Catalogue was principally an unadorned list of the exhibits. Although of use to visitors wishing to identify a specific item or to find their way to a particular department, its terse text was of limited value and lacked informative commentary. The Duke of Wellington would not have been alone in dismissing the Official Catalogue as ‘utterly useless!’3 – although unlike most visitors he was thoroughly familiar with the layout of the Exhibition, having visited it daily. In response to the many criticisms levelled at both catalogues, Charles Dickens’s popular weekly Household Words published the ‘Catalogue’s Account of Itself’ in its 23 August 1851 issue (see below, pp. 23–31). Written as a humorous autobiography, it offered an informed justification of ODIC and the Official Catalogue in terms of the immense difficulties that the compilers had encountered and overcome.

Recognizing that a cheaper and less austere guidebook was required, at the beginning ofJune the Commissioners issued the thirty-two-page Popular Guide to the Great Exhibition costing 2d., of which 26,000 copies were sold during the next four and a half months. A Companion to the Official Catalogue. Synopsis of the Contents of the Great Exhibition of 1851 (reproduced below, pp. 33–88) was published under the editorship of the mineralogist Robert Hunt. Priced at 6d., sales of the Synopsis reached 84,000, together with over 5,000 copies of a French translation.

Several commercial publishers also rushed out guidebooks soon after the Exhibition opened in order to compete with the official and semi-official publications in this potentially lucrative market. For example, in mid- to late June, the publisher Bradbury and Evans, which had earlier turned the ailing humorous magazine Punch into a commercial success, issued in four parts William Blan-chard Jerrold’s How to See the Exhibition: In Four Visits, at 6d. for each part or 2s. for the set. As the title indicates, the author (the son of Douglas Jerrold, a popular dramatist and a major contributor to Punch) offered visitors four complementary itineraries for touring the exhibits in the Crystal Palace.4 The example reproduced here is A Visit to the Great Exhibition by One of the Exhibitors, which sold at 6d. This rather unsophisticated production was rushed out within a fortnight of the Exhibition opening and was written (or perhaps co-written) by an artisan who was also an exhibitor. Such a guide is of particular interest because it reflected an artisan’s view of the Exhibition. An alternative account of the Exhibition and a widely different selection of exhibits was provided by ‘A Lady’s Glance at the Great Exhibition’, a guide published in six parts by the ILN. The author paid no attention to the machinery or philosophical instruments on display but instead dwelt extensively on the exhibits of jewellery, gloves, lace, cashmere and other fabrics. For many of the women who visited the Exhibition, ‘A Lady’s Glance’ would have been more helpful than either Hunt’s Synopsis or the Visit… by One of the Exhibitors.

At least thirty English-language guides to the Exhibition or, more generally, guides to London that included entries on the Exhibition were published in 1851. About ten of these metropolitan guides, including London as It Is To-Day, had been published before the Exhibition opened and were therefore of little use to the visitor trying to navigate the miles of exhibits inside the Crystal Palace. The remaining guides – approximately twenty – contained accounts that would have assisted visitors entering the Crystal Palace. A further twenty or so guides were issued in other languages, some of which were produced by British publishers and others published abroad.5

Several periodicals likewise produced fairly detailed descriptions of the Exhibition, such as The Times and the ILN, together with numerous articles on the contents of specific sections, such as the Medieval Court or the exhibits from Zollverein. Thus even before setting out for the Exhibition, potential visitors could determine which sections or exhibits most attracted their interest. Thus a fairly short article in the Family Economist; a Penny Monthly Magazine, for the Industrious Classes (see below, pp. 201–4) advised working-class visitors to plan their visit beforehand as their time in the Crystal Palace would be limited. The author also suggested which exhibits should be viewed and how to benefit from the experience. More advice for the visitor is contained in an article from the Religious Tract Society’s Visitor, or Monthly Instructor entitled ‘Memorable Things in the Great Exhibition’. A further section of a ‘Letter from a Country Visitor to her Friend in the North’ (see Volume 2, pp. 295–309), published in Sarah Ellis’s Morning Call, is also included as it provided its readers with advice on which sections were worth visiting and contained the author’s critical assessment of certain exhibits.

This section also includes a few diverse examples of the many other types of publication that were directed towards the visitor. A large number of poems and ballads were composed to celebrate the Exhibition, some of which were issued in periodical publications and collections of poetry or were printed as separate pamphlets or broadsheets. Three celebratory poems are reproduced here by the popular moralizing poet Martin Farquhar Tupper. In his short A Hymn for All Nations. 1851, Tupper praised God as the creator of all the works on display in the Exhibition, which he viewed as a means for uniting the nations. His Hymn was published with a musical score by S. Sebastian Wesley and with translations into twenty-three other languages – thus reflecting the international ethos of the Exhibition. Tupper’s poems are followed by two anonymous broadsheets: ‘Chrystal Palace’, which likewise celebrated the Exhibition, and the more cynical ‘The Exhibition and Foreigners’. These are examples of the large range of cheap, principally working-class, literature that was produced at the time of the Exhibition and sold by street vendors. Although the National Art Library, the John Johnson Collection, the Hagley Library at Wilmington, Delaware, and a few other archives have impressive collections of the ephemera generated by the Exhibition, many items are no longer available to the researcher.

The public flocked to contemporary entertainments as well as to the Exhibition itself. Every theatre, concert hall and amusement park in London sought to benefit from the tourist trade stimulated by the Exhibition. Theatres staged serious works by Shakespeare alongside such fashionable farces as William Brough’s ‘Apartments: Visitors to the Exhibition may be Accommodated’, in which an American, an (American) Indian, a Frenchman and a Scot caused mayhem by invading a London family’s normally sedate home for the duration of the Exhibition. Entertainments at Vauxhall Gardens, Cremorne Gardens and the Royal Surrey Zoological Gardens drew large crowds. At least sixty songs, waltzes, quadrilles and polkas on Exhibition themes were published, including the ‘Amazon Polka’, the ‘Greek Slave Waltz’, a ‘Grand Quadrille of All Nations’ and ‘Humours of a Parliamentary Visit’.6 The title pages of these works often included illustrations of the Crystal Palace surrounded by visitors dressed in the clothes of many nations. Melodies from several nations were often blended into a medley, as in J. R. Ling’s ‘Crystal Palace Waltzes’ (London: Harry May, [c. 1851]), which included ‘Rule Britannia’ (Britain), ‘Blue Bell[s] of Scotland’, ‘Groves of Blarney’ (Ireland), ‘Trab, Trab’ (Germany), ‘Isabel’ (Spain), a mazurka from Russia, ‘Pestal’ (Poland), ‘Il Segreto’ (Italy), ‘La Parisienne’ (France) and ended with an American polka. The popular French conductor Louis Antoine Jullien staged daily concerts at such venues as Drury Lane Theatre and the Royal Surrey Zoological Gardens, where he included such treats as his ‘Grand Exhibition Quadrille’ and ‘The Amazon and Tiger’ gallop. A poster for one of Jullien’s concerts is reproduced here, together with a humorous song, ‘The Glorious Exhibition’ by Andrew Park.

The final two documents in this section are religious tracts directed at visitors. Responding to the prospect of large numbers of visitors, especially foreign visitors, several religious organizations mobilized their not inconsiderable resources to provide spiritual sustenance to visiting Anglicans and inducements to Catholics, Jews and ‘heathens’ to convert to the Protestant faith. Extra Anglican services were mounted, including services in French and German; a series of Sabbath-day services led by leading evangelical preachers was held at Exeter Hall, the principal venue for evangelical events; and missionaries and colporters were employed to distribute tracts to visitors arriving at railway stations or entering Hyde Park. Copies of A Walk through the Crystal Palace and An Address to Foreigners Visiting the Great Exhibition of Arts in London (both of which are reproduced below) were thrust into the hands of visitors. The first of these tracts was published by the evangelical Religious Tract Society, and translations were also issued in six other languages. An Address to Foreigners was produced by the (Anglican) Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Hundreds of thousands of copies of both of these religious guides were printed and distributed.

Notes

- Advertisements appeared in The Times (17 April 1851, p. 9; 14 June 1851, p. 1) offering the services of guides and translators.

- ‘The Crystal Palace’, Mechanics’ Magazine, 55 (1851), p. 413. See also reviews, Mechanics’ Magazine, 54 (1851), p. 394; 55 (1851), pp. 331–2.

- A Great Man’s Friendship: Letters of the Duke ofWellington to Mary, Marchioness of Salisbury, 1850–1852, ed. Lady Burghclere (London: J. Murray, 1927), pp. 192–3.

- M. Slater, DouglasJerrold 1803–1857 (London: Duckworth, 2002); P. Leary, The Punch Brotherhood: Table Talk and Print Culture in Mid-Victorian London (London: British Library Board, 2010).

- Based on Dilke, Catalogue, with information from other sources.

- See Dilke, Catalogue, pp. 73–4, and ‘Collection of Music’, vols I and II at the National Art Library. ‘The...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- VI. Guides to the Exhibition and Other Materials Addressed to Visitors

- V. Visitors’ Accounts

- Editorial Notes

- Silent Corrections

- List of Sources