![]()

Part 1

How We Can Be Together

![]()

1

Introduction: Being Together

Kirsten Sadeghi-Yekta and Monica Prendergast

Kirsten: My last name is Sadeghi-Yekta. A married name—freely translated as “honestly unique”—from a part of the world I have never witnessed, nonetheless the wisdom of poems, smell of dill, mint, and Esfand are continuously present in our home. My maiden name, with a lesser brave meaning, is rooted in the Netherlands, where my parents and grandparents were born and raised. Growing up, it was through their eyes that I learned how storytelling reverses isolation and creates conditions for awareness and kindness. My mother took me to my first theatre performance when I was a toddler.

I am a recent white immigrant to the land that is known as Canada. Most importantly, I am a mother of two young children. I am also a theatre educator and applied theatre practitioner, and an advocate for work that welcomes the arts as an immigrant to their field. The lens that I carry in the world is clearly made up of “between-ness” and “beside-ness” (Taylor 2020: 6): parent, partner, daughter, academic, artist, immigrant, settler, multilingual, and many more.

My values and beliefs are predominantly formed by invaluable encounters with kind people and communities in unknown cultural territory, the majority of those facing hardship and conflict. Their teachings on humbleness (what truly matters), social justice (what is at stake), urgency of presence (how to be), transparency (when to enter and when to exit), generosity (how to give and receive), collective thinking (who matters), care (how to see each other), relationality (how to be together), and love (how to stay together) have brought me where I am today in my applied theatre practice.

Monica: I am a 60-year-old white, privileged upper-middle-class university professor who came to academic life mid-career. My prior career was in professional children’s theatre, primarily with Toronto’s Young People’s Theatre, and then as a high school drama educator. My ongoing values and commitments are feminist (seeking equity and justice for girls and women and all other groups pursuing equity); politically socialist (interested more in collectivity over individuality and in engaged democratic and active citizenship); processual (decades of drama and theatre-making have taught me the central importance of the process); and presence-oriented (as a trained actor, I understand presence in an embodied as well as an intellectual way). I am also influenced by critical pedagogy that is rooted in the work of Paolo Freire and his pedagogy of the oppressed (Freire 1971/2014) and in Augusto Boal’s transference of Freire’s work into theatrical forms (Boal 1979).

Bertolt Brecht’s work remains an influence for me on how theatre can move towards social revolution, as do works by Western English-language playwrights such as Henrik Ibsen, George Bernard Shaw, Athol Fugard, August Wilson, Tony Kushner, Suzan-Lori Parks, Caryl Churchill, and Edward Bond, among others. In other words, I believe in the sociopolitical and educational power of drama and theatre as a force for collective good. In the fields of drama and theatre education and applied theatre, I have been inspired by field founders Brian Way and Dorothy Heathcote, as well as by Gavin Bolton, Warwick Dobson, Carole Miller, John O’Toole, Cecily O’Neill, Helen Nicholson, Juliana Saxton, James Thompson, and Jonothan Neelands, among others.

Ethical Engagement

If being presente demands an ethical engagement, it seems that the terms of my presentness—racially, through social status, disciplinary training, and institutional location—calls attention to its many complexities. (Taylor 2020: 7)

Our goal in offering this up-front information about us, our identities and values, is to model the kind of ethical transparency we hope will follow across the chapters of this book. We also both work at the same academic institution in North America, which further dominates the voices we bring to this publication. What is our voice and where is it coming from? How is our presence implicated through the stories and words we have included in this book? That said, ethical practice demands that we be thoughtful about how we gather together and work collectively and creatively with participant groups. For example, when Kirsten collaborates with the Hul’q’umi’num’ Language & Culture Society on Vancouver Island, BC, or Monica works in prison theatre settings, our “presentness” and lenses of “besides-ness” will inherently create complex situations which require ethical engagement.

It is these small decisions, often made in the moment, that drive ethics in applied theatre practice. This book, and its array of chapters from international practitioners/scholars, focuses on these moments—in the field and on and off the stage—that enact the ethics of our practice. Our intent is to capture both past and present thinking about ethics in applied theatre, while also gesturing towards “the not yet and the not anymore” (Tuck 2009). This future-facing position is hopeful and inspired by Eve Tuck’s desire-based framework that seeks to look beyond the “frameworks that position communities as damaged” (416) and therefore simultaneously focuses on concepts such as self-determination, contradictions, and complexity: “Desire, yes, accounts for the loss and despair, but also the hope, the visions, the wisdom of lived lives and communities. It is involved with the not yet and, at times, with the not anymore” (417, original emphasis). Communities have so much more to offer than their internal “damages,” as Tuck argues, and if we are foregrounding ethical engagement here, then our initial step should be inspired by desire. We hope you enjoy your journey through these pages.

Ethical Concepts: How to Do “Good,” both Individually and Collectively Speaking

We are all responsible to the story. We are all responsible for the teachings we take from it and for how we will carry those teachings in our attitudes and behaviors. (Carter, Recollet and Robinson 2017: 218–19).

In this book, we offer multiple ways for scholars and practitioners in the field to think about the ethics of applied theatre as both a noun and a verb: ethics and “ethicking” (Laaksoharju 2008: 2) or “to act in an ethical way.” As in the demanding art form we practice, the challenge is to move the noun form of ethics from the page to the stage—to put it into action.

The book is divided into two parts. In the first four chapters we describe, discuss, and analyze our findings regarding ethics in the field of applied theatre in conversation with foundational literature and pioneers, including fundamental reflections in interviews with Indigenous artists from the land that is now known as Canada. Foregrounding diversity and prioritizing the voices we do not hear from enough are two of the ethical considerations of this book, and therefore we have explicitly chosen to have those voices heard right at the very beginning.

In the second part we have gathered together an international array of authors from Bangladesh, the UK, Canada, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, the United States, and the Philippines. We invited these authors to articulate an ethical concept derived from their practice, and have elicited rich, diverse, and complicated understandings of ethical approaches in the work that we do as a result. Across this book you will encounter ethics in the form of care for the human and more-than-human world, ceremony and medicine, micropolitical dilemmas, responsibility for the “other,” critical generosity, acceptance, vulnerability, courage, tensions, precarity, research ethics, colonial adventurism, embracing the essential void, and more. The fieldwork carried out in support of these chapters occurred within a wide range of settings, such as: in Indigenous communities (in Duncan, BC, and Toronto, Ontario, Canada); in a Massachusetts, US playback theatre space; in an intergenerational project in a Victoria, BC, elder care home with applied theatre students and patients living with dementia; in a creative dance project in Liverpool, UK, with those recovering from addiction; in refugee camps off the Greek coast; in a Toronto, Ontario, police training project; in a child rights project for internally displaced children in Jos, Nigeria; in projects carried out in remote fishing villages in the Philippines, and in a self-reflexive artist’s journey in Colombo, Sri Lanka.

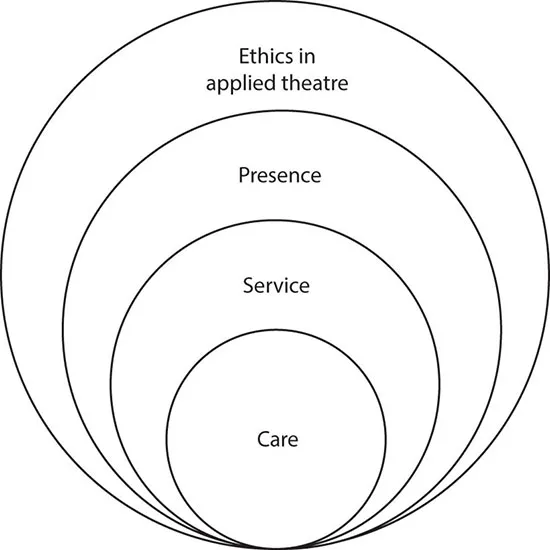

For us as co-editors, throughout the process of inviting these chapters—and in reading, rereading, and editing them—we have identified three “red threads” (Fox and Dauber 1999) that interweave amongst and across this collection. As playback theatre founder Jonathan Fox and co-editor Heinrich Dauber (1999) define it, “The ‘red thread’ is a metaphor from weaving, in which the red thread allows the weaver to follow the pattern, and is a common phrase in German for the ‘connecting element’” (65). These connecting ethical threads in applied theatre are service, presence and care (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Key principles of ethics in applied theatre.

The first thread of service has been brought to our attention in our engagement with Indigenous artists: for example, with playwright, artist and director Kim Senklip Harvey, who began our first conversation with the question “How can I be of service to you?” The giving back of service to communities is a key ethical principle held by many Indigenous peoples that relates to the values in our work. We provide an arts-based service to the participant groups and larger communities in which we work. Yet seeing ourselves as service workers may not be an obvious connection that all of us automatically make. Our position here is that if we can begin to see the work we do as applied theatre artists as a form of service, we will develop a cleaner understanding of reciprocity and collaboration. That in itself may lead to thinking through how those who live lives of service (such as nurses, doctors, social workers, and teachers) model and behave in ethical ways. Syed Jamil Ahmed’s chapter in this collection focuses on our shared responsibility to the “other” in ways that can be understood as service. Similarly, Anita Hallewas sees the notion of service expressed by the various arts groups working in refugee camps as exemplars in this regard. Also, in her contribution on the complexities of securing research ethics approval in our field, Sheila Christie urges for a revised process that serves the practice rather than limits it.

The second ethical thread of presence arises from Diana Taylor’s ¡Presente! The Politics of Presence (2020). Taylor’s timely contribution has allowed us to see the ways that presence informs ethical practice. To be truly present, one must be open to listening to, learning from, and responding with others; as Taylor says, ¡presente! means to be “present among, with, and to, walking and talking with others” (4). Taiwo Afolabi’s chapter on the ethics of precarity illustrates how the decisions made about his field research in Nigeria helped him to make fundamental ethical choices rooted in present circumstances. Dani Snyder-Young’s chapter on critical generosity allowed the playback theatre troupe she observed to trouble notions of white discomfort in the improvisational choices made in stories captured in the present moment. And Dennis Gupa’s fieldwork reflections from the Philippines clearly demonstrate the significance of being present during intricate research decisions. Led by his values, Gupa’s research took a different turn which brought him exactly where he needed to be. Our presence is at the heart of what we do; if we allow ourselves to be distracted from the focus needed to listen, see, learn, and respond, in the moment, we are undermining our ethical positions and potentially weakening the work of collective theatre-making and sharing. Being present is demanding, both emotionally and intellectually, but we see it as a crucial aspect of ethical practice.

Finally, the third red thread woven into the fabric of this text is care. James Thompson, whom we regard as one of the pioneer ethicists in applied theatre, has focused much of his recent work on the ethics of care (Thompson 2014, 2015; Stuart Fisher and Thompson, 2020). As Stuart Fisher points out in the introduction to Performing Care (2020):

Care emerges as being constitutively implicated within the concept of performance. After all, it is impossible to conceive of caring practice outside the parameters of how it is performed. In this sense, care, like live and theatrical performance, exists only as a live encounter and within a specific juncture of time and space. Furthermore, as with performance, care also involves forms of embodied knowledge. (7)

Here we see echoes of our notion of enacted ethics as a verb rather than a noun, and also the nested concepts of presence and service we have identified above. To care for others is to accept a responsibility for those others, ideally with a sense of reciprocity; a mutual giving and receiving that empowers rather than reinforces the simplistic notion of charity as a one-way power-over process. Stuart Fisher and Thompson helpfully remind us that caring holds political implications as well; as you will read in Chapter 4 in Kirsten’s interview with Thompson, he considers ethics and care ethics as a series of “micropolitical dilemmas” (see p. 72). How we engage with and respond to these many dilemmas—which are part and parcel of any applied theatre project—reflect both our own sociopolitical and cultural positions and those of the group with whom we are working. In her chapter on the implications of the concept of vulnerability in her applied theatre practice with people in recovery from addiction, Zoe Zontou interrogates her own thinking on which modes of care are appropriate while working with lived experiences, in particular looking at the risks of reinforcing re-stigmatization. Trudy Pauluth-Penner’s chapter focuses on the dilemmas that arose in an intergenerational project with senior participants living with dementia. Her sense of care infuses her writing, and informs the ethical concerns she experienced in staging a collaborative research-based play for her participants and others in a senior care home. Similarly, the role-play police training project that Yasmine Kandil presents in her chapter involves a level of care for those struggling with mental health issues. In its bold attempt to improve the sometimes violent and fatal outcomes that occur when police officers encounter people experiencing a mental health crisis, this project enacts a kind of sociopolitical care in its shared intent with the police officer participants to decrease the number of negative outcomes in these cases. Lastly, Ruwanthie de Chickera’s reflections on her applied theatre practice during the pandemic explore ways of self-care and what they have taught her about the ethics around the essential void in personal and professional settings.

We invite you to consider how these ethical red threads of service, presence, and care underpin the work carried out and reflected on across this book. Next, we focus on what emerged from the literature review on the discourse of ethics in applied theatre that lies ahead in Chapter 3. In focusing on the questions highlighted in this review, we are better able to see how the discourse has morphed and become more complex over time.

Defining Ethics: How We Can Be and Do “Good” Together

In our gathering and selection of sources tracing the discourse on ethics in our field, outlined in Chapter 3 of this collection, we were struck repeatedly by the number of ethical questions posed by authors. It appeared to us that ethical thinking in the midst of practice involves plenty of self-reflection, day to day, hour by hour, and moment to moment. Thus, what we offer here is a found poem crafted from the questions that emerged in our literature survey, presented as one way to begin to understand and appreciate the rich critical discourse on ethics in applied theatre (see Prendergast...