eBook - ePub

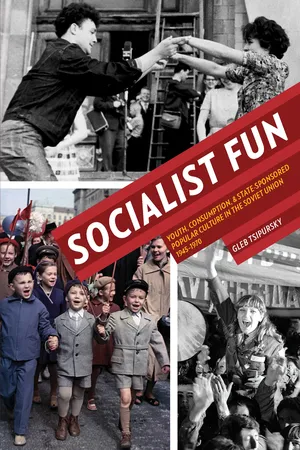

Socialist Fun

Youth, Consumption, and State-Sponsored Popular Culture in the Soviet Union, 1945–1970

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Socialist Fun

Youth, Consumption, and State-Sponsored Popular Culture in the Soviet Union, 1945–1970

About this book

Most narratives depict Soviet Cold War cultural activities and youth groups as drab and dreary, militant and politicized. In this study Gleb Tsipursky challenges these stereotypes in a revealing portrayal of Soviet youth and state-sponsored popular culture.

The primary local venues for Soviet culture were the tens of thousands of clubs where young people found entertainment, leisure, social life, and romance. Here sports, dance, film, theater, music, lectures, and political meetings became vehicles to disseminate a socialist version of modernity. The Soviet way of life was dutifully presented and perceived as the most progressive and advanced, in an attempt to stave off Western influences. In effect, socialist fun became very serious business. As Tsipursky shows, however, Western culture did infiltrate these activities, particularly at local levels, where participants and organizers deceptively cloaked their offerings to appeal to their own audiences. Thus, Soviet modernity evolved as a complex and multivalent ideological device.

Tsipursky provides a fresh and original examination of the Kremlin's paramount effort to shape young lives, consumption, popular culture, and to build an emotional community—all against the backdrop of Cold War struggles to win hearts and minds both at home and abroad.

The primary local venues for Soviet culture were the tens of thousands of clubs where young people found entertainment, leisure, social life, and romance. Here sports, dance, film, theater, music, lectures, and political meetings became vehicles to disseminate a socialist version of modernity. The Soviet way of life was dutifully presented and perceived as the most progressive and advanced, in an attempt to stave off Western influences. In effect, socialist fun became very serious business. As Tsipursky shows, however, Western culture did infiltrate these activities, particularly at local levels, where participants and organizers deceptively cloaked their offerings to appeal to their own audiences. Thus, Soviet modernity evolved as a complex and multivalent ideological device.

Tsipursky provides a fresh and original examination of the Kremlin's paramount effort to shape young lives, consumption, popular culture, and to build an emotional community—all against the backdrop of Cold War struggles to win hearts and minds both at home and abroad.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Socialist Fun by Gleb Tsipursky in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Russian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

IDEOLOGY, ENLIGHTENMENT, AND ENTERTAINMENT

State-Sponsored Popular Culture, 1917–1946

The postwar Stalin years, from 1945 to 1953, are widely depicted as a time of cultural militancy, when official policy denied the population’s desires for truly enjoyable cultural fun. Yet, a late 1945 Komsomol report commended Moscow clubs that “regularly show movies” and “hold evenings of youth leisure,” meaning youth-oriented events with dancing.1 In 1945 and early 1946, Komsomol official reports meant for internal policy guidance and Komsomol newspaper articles intended for public consumption frequently praised mass-oriented cultural institutions for staging entertaining and widely popular events with little or no ideological content, such as youth dances and foreign movies.2

To explain this unexpected cultural pluralism, the first part of this chapter examines the broader historical context of Soviet cultural production and provides the framework for the rest of the book by tracing the history of state-sponsored popular culture from its prerevolutionary origins through the end of World War II. It describes the basic institutions of organized cultural recreation and the primary tensions within them. The second part of the chapter focuses on the first postwar months, highlighting the tolerant policy toward state-sponsored popular culture. This postwar permissiveness resulted from the momentum of wartime cultural lenience, the immediate needs of physical reconstruction, and the Komsomol’s lack of capacity to enforce a hard-line cultural position. Organized cultural recreation demonstrates that the late Stalinist authorities, for a few short months, actually sought to appeal to the population and satisfy popular desires for a more pluralistic society. Official discourse in this period presented a commitment to building a form of communism that was not irreconcilable with a desire for western popular culture, allowing young people a surprising degree of cultural space for maneuver and marking a break with prewar Stalinist policies.

THE ANTECEDENTS OF THE SOVIET MASS CULTURAL NETWORK

The antecedents of Soviet state-sponsored popular culture date back to the late nineteenth century. Some Russian industrialists, progressive officials, philanthropists, and members of the intelligentsia began to sponsor for the lower-class urban population forms of popular culture, such as popular theaters and narodnye doma (people’s houses), intended to promote what they saw as healthy, appropriate, modern, and cultured leisure activities over supposedly wasteful or harmful ones, such as drinking.3 Liberal pedagogues also established organizations that provided cultural education activities for lower-class youth.4 Such initiatives responded to the social, economic, and cultural changes of industrialization and urbanization in imperial Russia. After the 1905 Revolution, there emerged autonomous workers’ clubs in which workers gathered for cultural self-education, aided by intellectuals eager to assist them. These clubs occasionally served as cover for underground political groups, including the Bolsheviks, exacerbating some tsarist officials’ antipathy toward organized cultural recreation.5

Organized cultural activities in Russia drew inspiration from institutions and developments in western Europe and North America.6 During the eighteenth century, British authorities suppressed working-class popular culture without offering enjoyable cultural recreation in exchange.7 By the nineteenth century, some middle-class social reformers began to sponsor what they perceived as fun, healthy, and “rational” leisure to British workers. The so-called working men’s clubs, based on middle-class culture, were meant to wean workers from the traditional sociability of bars and dance halls.8 In the United States, fin-de-siècle cultural elites disparaged the explosive growth of what they considered “low” cultural forms, such as blues and jazz, and instead promoted appreciation of “white” European “high” culture.9 Social activists promoted the need for organized leisure activities for young people, founding organizations such as the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts.10 These initiatives represented part of a broader sweep of social interventionist measures within industrializing countries aimed at improving the discipline, cultural level, productive capacity, and social welfare of the population.11

The parallels between the efforts of Russian and western social reformers hint at broader congruencies between their visions of an ideal future. Both wanted all of society to share their middle-class cultural values and engage in “rational” and “modern,” not “traditional” or commercial, leisure. Yet, these initiatives, without popular support or substantive government backing, had limited success in western countries and still less in imperial Russia.12

STATE-SPONSORED POPULAR CULTURE IN THE SOVIET UNION, 1917–1944

After the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks made state-sponsored popular culture a major sphere of activity for the Soviet party-state. The Bolsheviks took up many of the projects first elaborated by progressive professionals in late imperial Russia in the sphere of organized cultural recreation, just as they did in the realm of social reform more broadly.13 Moreover, at least some imperial-era mass cultural establishments carried much of their staff and spirit across the revolutionary divide.14

During the civil war of 1917–22, the party leadership emphasized the role of mass-oriented cultural activities in promoting loyalty to the new regime.15 The central government’s focus on the war, however, left ample space for grassroots initiatives. Individual factory committees, village councils, and Komsomol cells created a network of semiautonomous trade union, village, and youth clubs at the local level.16 These establishments often collaborated with the Proletkult, a semiautonomous cultural organization that strove to forge a “proletarian” culture via grassroots amateur cultural activities.17

Following the civil war and the transition to the New Economic Policy (NEP, 1922–28), these disparate activities coalesced into a centralized mass cultural network. This process involved a series of controversies about the most fitting cultural activities for the masses, which were part of larger debates about the best path to communism. Hard-line officials associated with the militant Left favored a rapid and coercive transition to communism led by an authoritarian elite committed to enacting Marxist-Leninist ideology with minimal consideration for public opinion. In contrast, soft-line cadres affiliated with the pluralistic Right supported a gradual path, one that relied more on persuasion over coercion, called for an alliance with nonparty technocratic specialists, and sought to both appeal to popular desires and elicit initiative from below as a means of achieving communism with grassroots support.18 These conflicts date back to disagreements within the prerevolutionary Bolshevik Party over whether to depend on a small and ideologically conscious revolutionary vanguard or trust in broad-based worker spontaneity to forge communism.19 While some officials consistently favored either soft- or hard-line viewpoints, most stood closer to the center of the political spectrum. They shifted their approaches and sometimes mixed elements from both, depending on the political, social, and economic situation, as well as on intraparty political struggles over leadership after Lenin’s demise. The Right and Left thus constituted fluid coalitions rather than well-defined blocs within the party.

The difference between the militant and pluralistic approaches found its reflection in state-sponsored popular culture. One conflict centered on the main priorities of this cultural sphere. Three possible areas of focus existed: first, promoting communist ideology, party loyalty, Soviet patriotism, and production needs; second, transforming traditional culture into an appropriately socialist one by instilling socialist norms of cultural enlightenment; and, finally, satisfying the population’s cultural consumption desires for entertainment and fun. More conservative officials held that state-sponsored popular culture needed to serve primarily as a “transmission belt” for Marxist-Leninist ideology, commitment to the party and the Soviet Union, and concern with production, with cultural enlightenment as a secondary goal. Soft-line cadres stressed satisfying the population’s desires for engaging and entertaining cultural activities, thus making cultural enlightenment secondary and political-ideological education last in importance.20 In another area of disagreement, pluralistic administrators expressed tolerance for western popular culture such as jazz music and fox-trot dancing, while those of a more militant persuasion condemned such cultural forms as ideologically subversive incursions of “foreign bourgeois” culture.21 Finally, those holding a conservative position demanded close control from above over cultural activities at the grassroots, while those toward the opposite end of the spectrum were more welcoming of popular initiative and grassroots autonomy.22 The latter point of tension proved especially significant for the fate of Komsomol-managed clubs that sprang up during the civil war and the early NEP period, with hard-liners expressing wariness of and striving to limit youth autonomy in state-sponsored cultural activities and those favoring a soft-line approach endorsing grassroots youth initiative.23

These divisions embodied two extremes of the political spectrum, with most cultural officials standing somewhere between these poles and holding a mixture of views. Further, their perspectives evolved over time due to changing domestic and external situations. Moreover, even those with the most extreme views largely agreed on the need for some cultural enlightenment and, more important, shared the common goal of trying to build a communist utopia. Still, the different stances generally correlated to fundamental tensions between conservative and liberal outlooks on the Soviet cultural field in the NEP years and afterward, continuing to inspire debates and reform drives throughout the history of the Soviet Union.

As the party-state recovered from the civil war and assumed more and more authority, those with more radical views increasingly dominated.24 This hardening process accelerated in 1928, as Stalin took the reins of power and put an end to the cultural pluralism of the NEP. The government centralized organized cultural offerings for the masses. It directed cultural institutions to carry a much heavier ideological load, censured light entertainment as unacceptable “cultural excess” (kul’turnichestvo), and harshly condemned western-style popular culture.25

By the mid-1930s, the party-state had begun to step back from most of its militant policies, declaring that it had achieved victory in constructing the foundations of socialism. The state began to invest more resources into improving living conditions.26 The number of clubs grew rapidly: between 1927 and 1932, the Soviet Union established 912 urban clubs, but, from 1932 to 1937, it established 2,951.27 Clubs began to include more light entertainment.28 The mid-1930s even witnessed a brief period of tolerance for western popular culture. Millions of people openly listened to and danced the fox-trot, tango, Charleston, Lindy hop, and rumba to jazz music played both by amateur ensembles and by professional jazz stars such as Alexander Tsfasman and Leonid Utesov.29 Still, top-down directives and oversight rather than grassroots initiative pervaded the mass cultural network. Furthermore, young amateur artists had to conform to the cultural standards imposed by cultural professionals.30

In the late 1930s, official policy turned toward isolationism and publicly expressed fear of foreign ideological contagion, along with declarations of Soviet superiority in all spheres of life.31 This development brought a renewed clampdown on jazz and western dancing, with jazz bands (dzhazy) either dispersed or forced to play variety (estrada) music. The repertoire for variety bands included an admixture of Russian classics, ballroom music, folk tunes, and mass-oriented patriotic and ideological Soviet songs. They also played a sovietized version of jazz cleansed of allegedly “decadent” elements. Official discourse expressed this division by speaking of acceptable sovietized jazz and contrasting it to harmful American-style jazz (amerikanskii dzhaz). Sovietizing jazz meant minimizing improvisation, syncopation, blue notes, and fast swinging feeling and instead playing in a smooth and slow style, with traditional jazz brass instruments, such as trumpets and saxophones, diluted by the addition of string and Soviet folk instruments. Fully choreographed and approved in advance by censorship organs, this sovietized jazz hardly measured up to the spontaneity and improvisation so essential to jazz as a musical genre; sovietized jazz most resembled big-band swing music, flavored with Soviet and especially Russian national themes.32

World War II caused tremendous disruption to youth lives across the Soviet Union and the European continent, including within the realm of Soviet state-sponsored popular culture.33 The state directed resources away from cultural activities, while most ordinary citizens had little leisure time or energy for culture. Despite these obstacles, some opportunities existed for mass music making and other forms of entertainment. Frequently, such entertainment occurred as a result of local initiatives by committed cultural enthusiasts. Moreover, concerts aimed at military personnel meant that cultural workers were engaged in efforts specifically for wartime needs. In fact, the government loosened the limitations on western popular culture imposed during the Great Purges. The party-state now welcomed American-style jazz tunes as a way of lifting the morale of the troops and populace and demonstrating a close relationship with wartime allies.34

THE MASS CULTURAL NETWORK

Regardless of the war, the framework of state-sponsored popular culture that emerged during the early 1930s survived largely unchanged throughout the Stalin period, and much of it carried over into the post-Stalin years as well.35 Trade unions controlled most urban and some rural clubs. Like the party, trade unions had a hierarchical structure, with local enterprise committees overseen by district (raion, also translated as neighborhood), city, province (oblast’ or krai, also translated as region), and republic-level committees. The Vsesoiuznyi Tsentral’nyi Sovet Professional’nykh Soiuzov (All-Union Central Trade Union Council) oversaw all trade unions. Government organs in each province, in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture, also established a number of large mass-oriented cultural institutions in most district capitals. This type of institution was known as a Dom narodnogo tvorchestva (House of folk creativity) or Dom khudozhestvennoi samodeiatel’nosti (House of amateur arts). These provided cultural guidance, assistance, and some limited oversight of organized cultural recreation. Village councils and large collective farms operated most of the smaller rural clubs. Parks of culture and leisure (parki kul’tury i otdykha), run by city-level cultural organizations, played a significant secondary role in the cultural life of young people in the larger cities from late spring to early fall, providing stages for concerts by pr...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Ideology, Enlightenment, and Entertainment: State-Sponsored Popular Culture, 1917–1946

- Chapter 2. Ideological Reconstruction in the Cultural Recreation Network, 1947–1953

- Chapter 3. Ideology and Consumption: Jazz and Western Dancing in the Cultural Network, 1948–1953

- Chapter 4. State-Sponsored Popular Culture in the Early Thaw, 1953–1956

- Chapter 5. Youth Initiative and the 1956 Youth Club Movement

- Chapter 6. The 1957 International Youth Festival and the Backlash

- Chapter 7. A Reformist Revival: Grassroots Club Activities and Youth Cafés, 1958–1964

- Chapter 8. Ambiguity and Backlash: State-Sponsored Popular Culture, 1965–1970

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index