- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

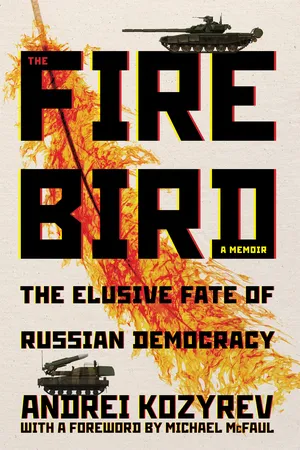

Andrei Kozyrev was foreign minister of Russia under President Boris Yeltsin from August 1991 to January 1996. During the August 1991 coup attempt against Mikhail Gorbachev, he was present when tanks moved in to seize the Russian White House, where Boris Yeltsin famously stood on a tank to address the crowd assembled. He then departed to Paris to muster international support and, if needed, to form a Russian government-in-exile. He participated in the negotiations at Brezhnev's former hunting lodge in Belazheva, Belarus where the leaders of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus agreed to secede from the Soviet Union and form a Commonwealth of Independent States. Kozyrev's pro-Western orientation made him an increasingly unpopular figure in Russia as Russia's spiraling economy and the emergence of ultra-wealthy oligarchs soured ordinary Russians on Western ideas of democracy and market capitalism.

The Firebird takes the reader into the corridors of power to provide a startling eyewitness account of the collapse of the Soviet Union, the struggle to create a democratic Russia in its place, and how the promise of a better future led to the tragic outcome that changed our world forever.

The Firebird takes the reader into the corridors of power to provide a startling eyewitness account of the collapse of the Soviet Union, the struggle to create a democratic Russia in its place, and how the promise of a better future led to the tragic outcome that changed our world forever.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Firebird by Andrei Kozyrev in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Russia versus the Soviet Union, 1991

1

The Russian White House under Siege

AUGUST 19, 1991, SHOULD HAVE BEEN A regular Monday morning, but it opened on an unexpected note. Instead of the news, all Russian TV and radio stations were broadcasting Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake. Audiences across the country understood at once that something serious had happened in politics. Ever since 1982, major events such as the deaths of Soviet leaders (three in the span of three years) had been announced after national broadcasting of this sort.

At age sixty, Gorbachev was on the young side and seemingly too healthy to follow his immediate predecessors. However, he was not immune to actions from Kremlin hard-liners fighting against his liberalization policies. And act they did: an announcer reported that Gorbachev had fallen ill at his state-owned dacha at a Black Sea resort. “The new Soviet leadership” in Moscow would reinstate socialist “law and order.”

At the time of the announcement I was already in a car and heading to the city from my state-owned dacha in a Russian government compound about fifteen miles from Moscow. Yeltsin occupied a house around the corner from me, though he had campaigned against such perks and had gained popularity by vigorously denouncing unwarranted privileges for top officials. The compound served as a kind of out-of-office meeting place for members of the Russian government.

As I drove in, I noticed signs of unusual activity near the local traffic police station. There were armored personnel carriers, solders with machine guns, and men in gray raincoats with that unmistakable KGB look surrounding them.

“Do we go on or make a U-turn?” The driver turned to me, his face pale. I knew what he meant. Fear of the KGB’s ruthless power was a key pillar of the Soviet regime.

I tried to make myself sound self-assured. “Go on, no problem,” I told him. Already it seemed that this Monday morning was to be marked by encounters with what Dostoyevsky had identified as both the greatness and the darkness of the Russian soul. The Tchaikovsky music represented the pinnacle of Russia’s cultural achievements, while the gray-clad men at the checkpoint evoked the horrors of the infamous Gulag Archipelago so vividly described by Alexander Solzhenitsyn. I saw before me a pivotal clash of extremes and was determined to take the right side. My Russian upbringing had instilled these kinds of literary images and moral absolutes in me ever since I was a boy.

As I returned to reality, I realized that the driver was following the usual route to the small, shabby mansion that housed the Russian Federation’s Foreign Ministry, located far from the central government region. I asked him to drop me instead at the “White House,” the colloquially named big white building that housed the Russian Parliament and the president’s office. If anything were to happen, it would be there.

On reaching the government building at about 8:30 a.m., I teased a young policeman at the entrance in a friendly way, as I always did. “Hi, tough guy, so what’s for breakfast in your handgun holder today?” He answered unexpectedly seriously: “Today it’s a revolver. We are here to protect you.” In numbers they represented no more than a squad and had no chance against the KGB Special Forces. Neither did we, I thought.

In the empty building I met Sergei Shakhrai, Yeltsin’s key legal adviser. He had won his seat in the Russian parliament by popular vote against communist opponents. With an ironic smile, he congratulated me because the coup d’état we had been expecting from the hard-liners for at least ten months had arrived, and, of course, no preparations had been made.

“It’s you who says it’s a coup,” I replied. “Though the plotters may be right about one thing: they are the new Soviet leadership.” This was true—President Gorbachev had appointed the leaders of the coup only a few months prior. The head of the group was none other than Gorbachev’s handpicked vice-president, Gennady Yanayev, who had been approved by the Soviet legislature only on a second vote, and only under heavy pressure from Gorbachev. The other leaders were the prime minister of the USSR and the top ministers of Gorbachev’s cabinet: the heads of the KGB, Defense, and Interior (police). “If Gorbachev has fallen ill, as they claim, why shouldn’t they impose law and order, even in his absence?”

“We should demand that Gorbachev speak to the public, however ill he is. If he cannot do this, it should be confirmed by the best doctors and publicly announced. Otherwise it is a coup!” Sergei declared. “I will call Yeltsin now. He is still at his dacha with a few aides. They are working on a statement condemning the coup. It’s very important that when we were on the way here, the KGB stopped neither of us. I shall advise him to return to Moscow. Is there anything you would like to suggest to him?”

“I think my ministry should call the Western embassies, as well as the media, and ask their representatives to come here at, say, 10:30 a.m. By that time Yeltsin will be either in the White House or in detention. In any case, the world should hear from us and learn what is going on.”

Shakhrai dialed Yeltsin’s dacha and spoke to Gennady Burbulis, Yeltsin’s closest aide at the time. Burbulis had been a professor of philosophy (Marxist philosophy of course, as all other schools of thought were banned) in Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg), the industrial center of the Urals. It was in Sverdlovsk that both he and Yeltsin had first won competitive elections to the parliament by running against communist opponents. Being a man of letters, Burbulis had a better knowledge of the key democratic concepts that both of them supported but he lacked Yeltsin’s charisma and ability to command big rallies. Known widely as the “Gray Cardinal,” he contributed hugely, perhaps decisively, to Yeltsin’s determined anti-communist stance in the critical years 1989 to 1992. Gennady was also a dear friend and mentor to me. That August morning he called back quickly. Our proposals were approved.

I immediately called my ministry and was pleased to find out that my key officers were in place and ready to do their jobs without needing explanation. It was a small staff—about sixty people. The Soviet Foreign Ministry housed thousands of diplomats and employees who were also doing their jobs, albeit working for the opposite political side.

At Burbulis’s suggestion, we went to his office to meet a group of high-profile supporters from civil society, headed by the academician Yuri Ryzhov, a well-known physicist and outspoken supporter of liberalization in Russia. Ryzhov possessed both conviction and charisma, but refused later offers to serve as prime minister, claiming lack of expertise in economics. Later I succeeded in drawing him into a government position—ambassador to France—where he performed brilliantly. On August 19, 1991, he had simply walked into an empty, unguarded White House and was busy calling friends from the democratically oriented political clubs that had sprung up in Moscow in the late 1980s. And they came. Within a short time, no fewer than thirty scientists, lawyers, movie stars, and journalists had appeared. Even the world-renowned cellist, Mstislav Rostropovich, had taken an early flight back to Moscow from abroad to join the resistance. I felt encouraged and honored to be on the same side as them. The fact that these leading figures had gathered in Burbulis’s office said a great deal about their faith in him, and our common cause.

Next we went to see the vice president of Russia, Alexander Rutskoi, who was checking his gun when we arrived. He told us that he was in charge of the defense of the White House against the coup plotters. Rutskoi almost matched Yeltsin for charisma and apparent determination, but his convictions were weaker, as was his commitment to (and knowledge of) civil society. Rutskoi was first and foremost a military man and a veteran of the Afghan war, for which he received the highest decoration, Hero of the Soviet Union. He first entered politics as a staunch communist and then, sensing the winds of change, broke with the party leaders to lead the so-called Communists for Reform.

Many democrats were concerned that Yeltsin had chosen Rutskoi instead of Burbulis or Shakhrai as a running mate in the presidential election campaign. I think he felt that Rutskoi would help attract parts of the broad military constituency. Unfortunately, his messy populism and habit of shouting hysterically at opponents instead of debating with them hardly endeared him to the white-collar civilian electorate and more thoughtful officers in the Soviet army. However, his bravery for the democratic side during the coup was critical and was the one important exception to his political behavior both before and after the coup.

After seeing Rutskoi, I headed to the office of the Russian prime minister, Ivan Silayev, a gray-haired man in his sixties. A former minister of aviation of the USSR, he had been approved by the Russian parliament as a compromise figure after Yeltsin’s more radical candidates, including Shakhrai, had been rejected.

That August morning, Silayev did not hesitate to denounce the coup on his own behalf and that of the cabinet, which had assembled to unanimously approve a resolution to that effect. Most of the Russian ministers were Silayev’s people, and his leadership was a decisive factor for them.

Before long Yeltsin’s successor as chair of the Russian parliament, Ruslan Khasbulatov, arrived and denounced the coup. Khasbulatov was an ambitious middle-aged former economics professor who had become a politician. But the fact remained that neither the Russian Federation’s president, nor the government, nor parliament had any power. The Soviet state still controlled everything at that moment. But we all understood that presenting a united front against the hard-liners gave us tremendous moral authority.

David and Goliath, This Time in Moscow

Standing by the window in Silayev’s office I watched shiny Mercedes and BMWs—then still rare in Moscow—driving western diplomats and reporters to the entrance of the building. At first it seemed strange that they were all coming from my right-hand side as I looked out the window. Then, turning my gaze to the left, I saw the unimaginable taking shape: battle tanks were creeping in single file along the bridge over the Moscow River toward the government building. These vehicles were rare guests too. They had never been seen before in the city other than in military parades on national holidays. In contrast to those dusty beasts they were sparkly clean. Mentally it was quite a captivating juxtaposition. It epitomized the choice Russia confronted at the time and has been facing ever since: to move forward to Western-style democracy or be drawn back into militaristic authoritarianism.

The symbolism of the hard-liners’ move was no less obvious. The outsized display of force harked back to the worst Soviet traditions of intimidation. It could also be taken as a signal of doggedness, and fear crept between my shoulders.

A guard burst into the room: “Mr. Prime Minister and you gentlemen, please pick up some guns from the reserve stock!”

Silayev immediately countermanded the order: “No! Our weapons should be different. We’ll go to the press hall and tell the truth about what’s happening to the diplomats and media representatives who have already arrived.”

Walking to the Press Hall, someone recalled an old joke about a man calling the KGB to protest that his lost parrot spoke only for itself. No one laughed.

The press hall was almost full. On my way in, I saw diplomats from the Western countries. Poland, Hungary, and other Central and Eastern European nations that until recently had been in the sphere of Soviet influence were represented at the ambassadorial level. With memories of Soviet crackdowns on democratic movements in their own countries still fresh in their minds, they were quick to grasp the situation and show support.

Yeltsin read out the statement denouncing the coup and calling for Gorbachev’s return, and turned to us with a question. Why had the coup plotters not hesitated to bring tanks into Moscow, and yet allowed him to hold a press conference? The answer was unanimous: the soldiers and officers, including the KGB agents, were reluctant to use force against the first ever popularly elected Russian leader, with an election just two months away. And, like most Russians, they were fed up with Soviet rule.

In the middle of the Q&A session, Yeltsin asked me to take over and he left the hall. In another moment CNN and the other world news outlets were transmitting video of Yeltsin shaking hands with the soldiers, climbing up on a tank, and denouncing the hard-liners. The photograph of the Russian president standing atop a tank was reproduced in news media all over the world and has become an enduring image of Russia’s anti-communist revolution.

Small but fast-growing crowds began gathering around the White House in support of the revolution and the reformers. Within a few hours they had formed a full circle, a “living wall,” around the building. We were winning in the court of domestic public opinion.

The overwhelming and unrestrained power of the communist dictatorship, which had terrorized Russia for more than seventy years, seemed unable to reinstate itself in the very center of Moscow. Yet the tanks were still there, and the government building was under siege. Only one telephone line connecting Moscow to the outside world was functioning. No cars were permitted to enter or leave. What we had won could be described less as a victory and more as a chance to succeed.

The leaders of the Soviet republics were silent, except for the heads of the three Baltic republics who asked the West for protection and recognition of their sovereignty. Others, as we learned later, were occupied with consolidating their power and declaring independence. The major Western capitals were very cautious in their comments.

Yeltsin dispatched his old friend Oleg Lobov to Sverdlovsk, where they had worked in the Communist Party regional department, to organize a backup office in case the coup plotters squeezed us out of Moscow. I was sent abroad with a written order signed by Yeltsin to promote the position of the legitimate president and government of the Russian Federation. No government in exile was mentioned in the document, because it could be used against us if I were detained before crossing the Soviet border. But Yeltsin believed that according to international custom, a minister of foreign affairs could, without special credentials, declare a government in exile if the legitimate government at home had been overthrown.

“Tell the officials and the media when you arrive that you have credentials from the president of Russia to set up a government in exile,” Yeltsin said to me during a meeting before my departure. “So, these crazy guys here will know that even if they kill me, they will still have a big problem.”

I was honored by his trust in me and told him so. I also pointed out that I didn’t think the situation in Moscow would ever reach the level where it would require a government-in-exile. While prenotification of the relevant officials would be helpful, it should be kept confidential as it was important not to weaken the message of our determination to win in Russia. Everybody, including the criminals in the Kremlin, should be aware of our resolve to rescue Gorbachev and bring him back.

I mentioned Gorbachev, fully aware of what might follow and was hardly surprised by the president’s emotional response. “I know that you like Gorbachev more than me. They’ve told me that many times. But don’t forget you are going as the envoy of the Russian Federation’s president and government.” For a moment Yeltsin could not suppress his envy of and disdain for Gorbachev. But he quickly returned to the matter at hand. “You know, Andrei Vladimirovich, how much we count on your professionalism. I concur with making no public statements about the government-in-exile for the time being. Why should we be constantly calling for Gorbachev’s return? Shakhrai started this. And I agreed to refer to Gorbachev at the press conference. But those soldiers and people downstairs couldn’t care less. They support the Russian president.”

“Shakhrai and I, as well as Burbulis and those people standing outside, have no illusions concerning Gorbachev,” I said to Yeltsin. “We all know the difference between him and the first popularly elected president of Russia. In the West, however, many are still suffering from Gorbymania. We should come out as defenders of law and order and call Gorbachev back. That would make us, not the plotters, worthy of international support.”

“You are probably right. But first we must defeat the plotters, and then see to it that Gorbachev cannot appoint them, or clowns like them, again.” He was deep in thought, almost speaking to himself.

“I admire your courage, Boris Nikolayevich, and my heart will be with you.”

He stood up; we embraced. This is the right person in the right place and at the right time to change history, I thought as I left his office.

“Stand by Us”

As I was waiting to leave for the airport, I called my friend Allen Weinstein, then president of the Center for Democracy in Washington, DC, and later archivist of the United States. I briefed him on the situation in Russia, and he told me of the somewhat confused and mixed reaction in the West. Allen suggested that I write a commentary for the world media. I agreed. We started to sketch out the text, hoping not to be disconnected, over the next fifteen minutes. Weinstein finalized the article, working from notes, and the following morning (August 21) it appeared as an op-ed in the Washington Post. It was the first direct word from the rebellious Russian White House to the American public, and its title spoke for itself: “Stand By Us.”

Around midnight I left the White House. The scene that greeted me exceeded my wildest imaginings. The road leading away from the building goes along an embankment of the Moscow River, offering a gorgeous view over its broad and leisurely waters. On the opposite shore the iconic silhouette of one of Stalin’s seven “wedding cake” skyscrapers rose skyward. In the park in front of it stands a huge statue of the prominent Ukrainian poet and national hero, Taras Shevchenko. The mighty bronze figure on top of the granite rock is posed taking a resolute step forward, his head bent in deep thought. It was a perfect figure for that historic moment.

On my side of the river, near the White House, thousands of people were circulating in a friendly and cheerful crowd. Guys and gals in blue jeans (made in the United States) were mingling with soldiers of the same age in military fatigues stationed near their tanks. Occasionally they would climb up on the tanks together and sit there, sharing homemade sandwiches and singing pop songs. They were simultaneously having fun and preparing to mobilize. The soldiers were waiting for orders to clarify why they had been deployed to the center of the city. Would those orders mean storming the White House, perhaps even firing into the crowd of civilians with whom they shared so much? And what about the civilians: would they commit themselves to stopping the soldiers in case of attack? The air was electric.

I called home, my wife Irina had no illusions about the dangerous situations we were in, but was calm and brave. She said that our daughter, Natalia, then eleven years old, would stay the night at the home of a classmate whose parents had offered a refuge for “our foreign minister’s family.” They, too, had heard the music and knew what it meant....

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Author’s Note

- Introduction: A Matter of Life and Death

- Part I. Russia versus the Soviet Union, 1991

- Part II. Climbing a Steep Slope, 1992–1994

- Part III. The Downward Slope, 1994–1996

- Epilogue: Can Russian Democracy Rise Again?

- Acknowledgments

- Index