- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Toward a Civil Discourse examines how, in the current political climate, Americans find it difficult to discuss civic issues frankly and openly with one another. Because America is dominated by two powerful discourses—liberalism and Christian fundamentalism, each of which paints a very different picture of America and its citizens' responsibilities toward their country-there is little common ground, and hence Americans avoid disagreement for fear of giving offence. Sharon Crowley considers the ancient art of rhetoric as a solution to the problems of repetition and condemnation that pervade American public discourse. Crowley recalls the historic rhetorical concept of stasis—where advocates in a debate agree upon the point on which they disagree, thereby recognizing their opponent as a person with a viable position or belief. Most contemporary arguments do not reach stasis, and without it, Crowley states, a nonviolent resolution cannot occur.Toward a Civil Discourse investigates the cultural factors that lead to the formation of beliefs, and how beliefs can develop into densely articulated systems and political activism. Crowley asserts that rhetorical invention (which includes appeals to values and the passions) is superior in some cases to liberal argument (which often limits its appeals to empirical fact and reasoning) in mediating disagreements where participants are primarily motivated by a moral or passionate commitment to beliefs.Sharon Crowley examines numerous current issues and opposing views, and discusses the consequences to society when, more often than not, argumentative exchange does not occur. She underscores the urgency of developing a civil discourse, and through a review of historic rhetoric and its modern application, provides a foundation for such a discourse-whose ultimate goal, in the tradition of the ancients, is democratic discussion of civic issues.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Toward a Civil Discourse by Sharon Crowley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 ON (NOT) ARGUING ABOUT RELIGION AND POLITICS

In the spring of 2003, during the American invasion of Iraq, my friend Michael attended a peace vigil. As he stood quietly on a street corner with other participants, a young man leaped very close to his face and screamed: “Traitor! Why don't you go to Iraq and suck Saddam's dick?” Michael was taken aback by the vehemence with which the insult was delivered as much as by its indelicacy. Why, he asked, does disagreement make some people so angry?

This is and is not a rhetorical question. That is to say, it is a question about rhetoric, and the question requires an answer. In A Rhetoric of Motives Kenneth Burke asserts that “we need never deny the presence of strife, enmity, faction as a characteristic motive of rhetorical expression” (20). But in America we tend to overlook the “presence of strife, envy, faction” in our daily intercourse. “Argument” has a negative valence in ordinary conversation, as when people say “I don't want to argue with you,” as though to argue generates discord rather than resolution. In times of crisis Americans are expected to accept national policy without demur. Indeed, to dissent is to risk being thought unpatriotic.

Inability or unwillingness to disagree openly can pose a problem for the maintenance of democracy. Chantal Mouffe points out that “a well-functioning democracy calls for a vibrant clash of democratic political positions. If this is missing there is the danger that this democratic confrontation will be replaced by a confrontation among other forms of collective identification” (Democratic 104). When citizens fear that dissenting opinions cannot be heard, they may lose their desire to participate in democratic practices, or, to put this in terms congenial to Mouffe's analysis, they may replace their allegiance to democracy with other sorts of collective identifications that blur or obscure their responsibilities as citizens.

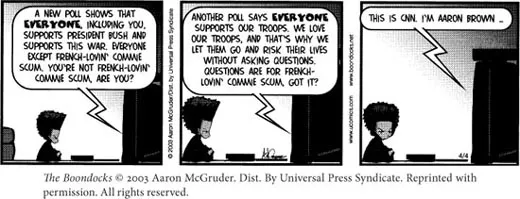

Something like this seems to have happened in America. Members of a state legislature flee the state's borders in order to avoid voting on a bill that will gerrymander them out of office. Other legislatures are unable to cooperate well enough even to settle on a method of deliberation. Authorized public demonstrations are haunted by the possibility of violence. Media pundits tell us that “the nation” is “polarized.” Citizens do not debate issues of public concern with family, friends, or colleagues for fear relationships will be irreparably strained in the process. Joan Didion suspects that we refrain from discussing current events because “so few of us are willing to see our evenings turn toxic” (23). Didion writes that some issues, such as America's relations with Israel, are seen as “unraisable, potentially lethal, the conversational equivalent of an unclaimed bag on a bus. We take cover. We wait for the entire subject to be defused, safely insulated behind baffles of invective and counterinvective. Many opinions are expressed. Few are allowed to develop. Even fewer change” (24). Clearly this state of affairs threatens the practice of democracy, which requires at minimum a discursive climate in which dissenting positions can be heard.

Discussion of civic issues stalls repeatedly at this moment in American history because it takes place in a discursive climate dominated by two powerful discourses: liberalism and Christian fundamentalism.1 These two discourses paint very different pictures of America and of its citizens' responsibilities toward their country. Liberalism is the default discourse of American politics because the country's founding documents, and hence its system of jurisprudence, are saturated with liberal values. The vocabulary of liberalism includes commonplaces concerning individual rights, equality before the law, and personal freedom. Because of its emphasis on the last-named value, liberalism has little or nothing to say about beliefs or practices deemed to reside outside of the so-called public sphere. Indeed, in the last fifty years American courts have imagined a “zone of privacy” within which citizens may conduct themselves however they wish, within certain limits (Gorney 135-39). Fundamentalist Christians, on the other hand, aim to “restore” biblical values to the center of American life and politics. If they have their way, Americans will conduct themselves, publicly and privately, according to a set of beliefs derived from a fundamentalist reading of the Judeo-Christian religious tradition. One might say, then, that the central point of contention between adherents of these discourses involves the place of religious and moral values in civic affairs: should such convictions be set aside when matters of state policy are discussed, or should these values actually govern the discussion?

Because most Americans subscribe at the very least to the liberal value of individual freedom, the increasing popularity and influence of Christian fundamentalist belief has created debate, often acrimonious, on many issues of current public concern: abortion rights, prayer in school, same-sex unions, and censorship, as well as more explicitly political practices such as taxation, the appointment of judges, and the conduct of foreign policy. And even though the variety of fundamentalist Christianity I will here call “apocalyptist” is professed by a minority of religious believers in America, its adherents' vocabulary and positions have indeed begun to influence policy developed in civic spheres (see chapter 5). Furthermore, terms and beliefs invented within this discourse (“family values,” “partial-birth abortion,” “judicial activism”) have entered common parlance—the discursive realm from which rhetorical premises are drawn.

I forward the ancient art of rhetoric as a possible anodyne to this situation, in the hope that rhetorical invention may be able to negotiate the deliberative impasse that seems to have locked American public discourse into repetition and vituperation. I hope to demonstrate that the tactics typically used in liberal argument—empirically based reason and factual evidence—are not highly valued by Christian apocalyptists, who rely instead on revelation, faith, and biblical interpretation to ground claims. We thus need a more comprehensive approach to argument if Americans are to engage in civil civic discussion. Rhetorical argumentation, I believe, is superior to the theory of argument inherent in liberalism because rhetoric does not depend solely on appeals to reason and evidence for its persuasive efficacy. Since antiquity rhetorical theorists have understood the centrality of desires and values to the maintenance of beliefs. Hence rhetorical invention is better positioned than liberal means of argument to intervene successfully in disagreements where the primary motivation of adherents is moral or passionate commitment. Susan Jacoby provides a compelling description of the role played by passion in the maintenance of belief and of the difference it makes in terms of persuasiveness: “In August 2003, when federal courts ordered the removal of a hefty Ten Commandments monument from the Alabama State Supreme Court building, thousands of Christian demonstrators converged on Montgomery…. They were not only outraged but visibly grief-stricken when the monument was moved out of sight. It was, one demonstrator said with tears in his eyes, like a death in the family. Secularist civil libertarians who had brought the lawsuit, by contrast, spoke in measured objective tones about the importance of the First Amendment's separation of church and state” (364). I hope to establish that deeply held beliefs are so tightly bound up with the very bodies of believers that liberals' relatively bloodless and cerebral approach to argument is simply not persuasive to people who do not accept liberalism or whose commitment to liberalism is less important to them than are other sorts of convictions.

I need to say up front, however, that rhetoric is not a magic bullet. A rhetorician can make no promises when it comes to changing minds, particularly those of people who are invested in densely articulated belief systems. Usually people invest in such a system because it is all they know, or because their friends, family, and important authority figures are similarly invested, or because their identity is in some respects constructed by the beliefs inherent in the system. Rejection of such a belief system ordinarily requires rejection of community and reconstruction of one's identity as well. Hence the claim I make in this book for the efficacy of rhetoric is limited: it will work better in the present climate than liberal argumentation because it offers a more comprehensive range of appeals, many of which are considered inappropriate in liberal thought. In order to be of use in a postmodern setting, however, the conceptual vocabulary of rhetoric must be rethought. If this can be accomplished, rhetoric can become a productive means of working through issues that concern citizens.

American Liberalism and the Second Coming

Mouffe and Ernst Laclau define hegemony as “the achievement of a moral, intellectual and political leadership through the expansion of a discourse that partially fixes meaning around nodal points. Hegemony…involves the expansion of a particular discourse of norms, values, views and perceptions through persuasive redescriptions of the world” (qtd. in Torfing 302).2 A discourse that achieves hegemony in a given community is so pervasive there that its descriptions of the world become thoroughly naturalized. Furthermore, its conceptual vocabulary literally “goes without saying”—that is, its major terms are seldom subjected to criticism. Liberalism has enjoyed hegemonic status in American discourse since the early nineteenth century. Apocalyptism has an even longer history in America, but it has never achieved the hegemonic status enjoyed by liberalism or by mainstream Christianity, for that matter. I will argue that at this moment in history, however, a version of Christian fundamentalism, driven by apocalyptism, is in hegemonic contention with liberalism because it motivates the political activism of the Christian Right. The considerable political and ideological successes of this faction have rendered the terms and conjectures of liberalism available for examination and possible redescription. In democracies a serious challenge to a hegemonic discourse is likely to create uneasiness and rancor because ownership of the master terms of political discourse, and hence of political and cultural power, is at stake.

Liberalism emerged as a set of political beliefs and practices in company with capitalism during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.3 According to Anthony Arblaster, the fundamental values of political liberalism are freedom, tolerance, privacy, reason, and the rule of law (55). In an American context equality should be added to this list. There are many varieties of liberalism, among them the classical liberalism of Mary Wollstonecraft; the utilitarian liberalism of John Stuart Mill; the welfare-state liberalism of Franklin Roosevelt; and the contemporary merger of liberalism with free-market capitalism in the ideology called “neoliberalism,” exemplified by the centrist politics of Bill Clinton (Lind). Welfare-state liberalism is no longer influential in American politics; Senator Ted Kennedy, who supports subsidized health care for all Americans, is a lonely avatar on the national level. Nonetheless, surveys establish that most Americans still support welfare-state liberal programs such as Social Security and Medicare. More important from a rhetorician's point of view, America's founding documents are saturated with liberal principles. Hence children and adults who apply for citizenship are exposed to liberal beliefs while becoming acquainted with America's civic lore. Not the least notable assertion in that lore is that “all [citizens] are created equal.” The necessity of placing brackets in this famous line points up the fact that exclusions were endemic to Enlightenment liberalism. Despite this, the liberal values of equality and liberty are the most inclusive political values ever incorporated into a polity, and they have been used repeatedly since the nation's founding to extend civic and civil rights to previously excluded groups (Condit and Lucaites). Liberal beliefs permeate our judicial system, as well as our daily talk about “freedom,” “equality,” “privacy,” and “rights.” That is to say, bits and pieces of liberal ideology still circulate widely in public discourse in the form of commonplaces, and it is on the level of common sense that liberalism (still?) enjoys hegemonic status.

I am aware of course that liberalism is ordinarily contrasted to conservatism. However, nonreligious conservatism is a minority discourse in America, as is illustrated by the cases of neoconservatism and libertarianism. Our national politics has moved to the right since the 1970s because of a powerful alliance forged during that decade between conservative political activists and apocalyptist Christians (Diamond, Spiritual 56-60). The social agenda that motivates the religious Right is of little interest to economic conservatives, but their acquiescence to it was required in order to amalgamate a voter base that was sufficiently extensive to elect conservatives to office. While this collaboration has not been entirely free of ideological strife, it has achieved astonishing results in elections at all levels. Moreover, some of its slogans and typical patterns of thought have now become commonplace. An example can be found in the morphing of the term liberal itself; the term used to refer to someone who espoused welfare-state political positions and/or who believed that moral and social behavior was a matter for individuals to decide. But liberal can now be wielded as a term of opprobrium, meaning something like “free-thinking, immoral elitist.”

Like liberalism, Christianity is a hegemonic discourse in America, as is demonstrated by the fact that it is difficult for non-Christians to remain unaware of Christian belief and practice. Church bells ring in nearly every American neighborhood on Sunday mornings, and during periods of Christian celebration, such as Christmas and Easter, every mall and many homes are decked out with images and symbols evoking these commemorations. In a study undertaken in 2001 more than three-quarters of the Americans surveyed identified themselves as Christians.4 Of course there are many varieties of Christian belief. In America most Christians are Protestants, although a significant minority (25 percent) of those who identify themselves as Christian are Roman Catholic. The variety of Christian belief in which I am interested here typically flourishes among conservative Protestants called “evangelicals” or “fundamentalists,” although apocalyptist beliefs may be held by mainstream Protestants and Roman Catholics as well.5 As we shall see, scholars and pundits do not agree about how many people can accurately be called “conservative Christians.” Here I accept Christian Smith's careful estimate: about 29 percent of the American population so identify themselves (Christian 16). Here the term apocalyptism signifies belief in a literal Second Coming of Jesus Christ, an event that is to be accompanied by the ascent of those who are saved into heaven.6 Apocalyptists believe that this ascent, called the “Rapture,” will occur either prior to or during the tribulation, a period of worldwide devastation and suffering. Finally, at the last judgment, evil will be overcome and unbelievers will be condemned to eternal punishment. I argue that this theological scenario founds a political ideology, a set of political beliefs subscribed to by millions of Americans who may or may not accept as literal truth the end-time prophecies announced in the Christian Bible. Domestically this politics favors the infusion of biblical values into American law and maintenance of the patriarchal nuclear family. Its foreign policy is aggressively nationalist.

The phrase “liberal Christian” is not an oxymoron. Many of America's founders were practicing Christians, and yet they based the Constitution of the United States on the Enlightenment principle of natural human rights. In his study of America in the early nineteenth century Alexis de Toqueville claimed that Christianity actually reinforced the liberal values that inform America's founding documents, noting that Christianity held “the greatest power over men's souls, and nothing better demonstrates how useful and natural it is to man, since the country where it now has widest sway is both the most enlightened and freest” (1: 290-91). However, Randall Balmer argues, against de Toqueville, that there is no “mystical connection” between religion and politics in America. In his opinion the disestablishment clause of the First Amendment, barring the institution of a state religion, has in fact insured maintenance of political stability. Balmer writes that a “cornucopia of religious options” has “contributed to America's political stability by providing an alternative to political dissent” (Blessed 39). In other words, potent beliefs that could threaten liberal democracy regularly drain off into religious enthusiasm. Balmer's example is the emergence of the Jesus movement out of the political turbulence of the 1960s.

The relation of apocalyptism to conservative Christian political activism is complex. On its face apocalyptism would seem to obviate an interest in politics. Someone who believes that she is at any moment about to be snatched up into heaven is unlikely to be interested in earthly matters. Charles Strozier remarks, for example, that “democracy is not well grounded in the lives of…Americans…who believe in the Rapture” (120). Nevertheless, public figures who are associated with Christian political activism, such as Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell, do hold apocalyptist beliefs, and apparently they do not find it difficult to reconcile the two. Such reconciliation became easier during the 1980s, when interpreters of biblical prophecy modified the apocalyptic narrative in order to suggest that political involvement was necessary in order to hasten the advent of the end time (see chapter 4). Nor does subscription to conservative Christian beliefs necessarily entail either conservative politics or political activism. Based on his survey of evangelical opinion, Christian Smith concludes:

Evangelicals are often stereotyped as imperious, intolerant, fanatical meddlers. Certainly there are some evangelicals who exemplify this stereotype. But the vast majority, when listened to on their own terms, prove to hold a civil, tolerant, and noncoercive view of the world around them…. The strategies for influence of evangelical political activists and those of ordinary evangelicals are obviously worlds apart. The former can be alarmist, pretentious, and exclusivist. The latter emphasize love, respect, mutual dialogue, taking responsibility for oneself, aversion to force and confrontation, voluntaristic ground rules of engagement, and tolerance for a diversity of views. Clearly, many of the evangelical political activists who are in the public spotlight do not accurately represent the views and intentions of their supposed constituency. (The fact that they are largely self-appointed, not elected, with little accountability to the grassroots majority may help to explain this.) Yet many outsiders make little distinction between the two, and the masses of ordinary evangelicals around the country remain misunderstood, their views thought of as no different from those of Randall Terry, James Kennedy, Pat Buchanan, and other evangelical leaders of similar persuasion. (Christian 48)

In fact some fundamentalist Christians still adhere to the policy of withdrawal from worldly matters that was widely adopted after the Scopes trial in 1925 (Carpenter). Nancy Ammerman points out that prior to the 1980s “pastoring churches and establishing schools had long been the more likely strategies of people who called themselves fundamentalists. Not all saw politics and social change as their mission, and many had discounted such activities as useless, even counterproductive” (“North American” 1). Ammerman also notes that “the name ‘fundamentalist' is not necessarily synonymous with ‘conservative,' because it is possible to accept fundamentalist Christian beliefs, such as the Virgin Birth or the Resurrection, while seeking naturalistic rather than supernatural explanations for them” (“North American” 2). Some fundamentalist and evangelical Christians in fact hold liberal political beliefs. Spokespersons for this position, such as those who write for Sojourners.com, regularly express dismay about the agenda and tactics of the Christian Right. In addition, subscription to the political agenda forwarded by the Christian Right can be justified on nontheological grounds. That is to say, conservative Christian voters who support this agenda may do so for reasons that have little direct correlation with apocalyptism: they may wish to protect their families from what they see as a decline in moral values, for ex...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. On (Not) Arguing about Religion and Politics

- 2. Speaking of Rhetoric

- 3. Belief and Passionate Commitment

- 4. Apocalyptism

- 5. Ideas Do Have Consequences: Apocalyptism and the Christian Right

- 6. The Truth Is Out There: Apocalyptism and Conspiracy

- 7. How Beliefs Change

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index