- 546 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Now in its second edition, this book takes a fresh, probing look at one of the greatest human tragedies in modern history.

Beginning with a detailed overview of the history of the Jews and their two-millennia-old struggle with the anti-Judaic and anti-Semitic prejudice and discrimination that set the stage for the Holocaust, David M. Crowe discusses the evolution of Nazi racial policies, beginning with the development of Adolf Hitler's anti-Semitic ideas, their importance to the Nazi movement in the 1920s and 1930s, and their expanding role in the evolution of German policies leading to the Final Solution in 1941 – the mass murder of Jews throughout Nazi-occupied Europe. The German program involved the creation of death camps like Auschwitz and Treblinka and mass murder sites throughout Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. While the Jews were the principal victims, other groups who were deemed racial or biological threats to Hitler's goal of creating an Aryan-pure Europe were also targeted, including the Roma and the handicapped. This book discusses Nazi policies in each country in German-occupied Europe as well as the role of Europe's neutrals in the larger German scheme-of-things. It also takes an in-depth look at liberation, Displaced Persons, the founding of Israel, and efforts throughout the western world to bring Nazi war criminals and their collaborators to justice. This second edition includes a new chapter on the importance of memory and the Holocaust, the evolution of interpretative Holocaust scholarship and media, recent controversies about national responsibility, and the work of Holocaust museums, archives, and libraries in Israel, Germany, Poland, and the United States to promote Holocaust education and memory. It concludes with the rise of Neo-Nazism, white nationalism, and other movements in Germany and the United States, and their relationship to questions about Holocaust memory and its lessons.

Comprehensive and offering a detailed historical perspective, this is the perfect resource for those looking to gain a deep understanding of this tragedy.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1Jewish HistoryAncient Beginnings and the Evolution of Christian Anti-Judaic Prejudice Through the Reformation

CHRONOLOGY

- —Second Millenium b.c.e. (Before the Common Era): Abraham receives covenant from Hebrew God YHWH

- —Thirteenth Century b.c.e.: Moses leads Hebrews on Exodus and receives Ten Commandments

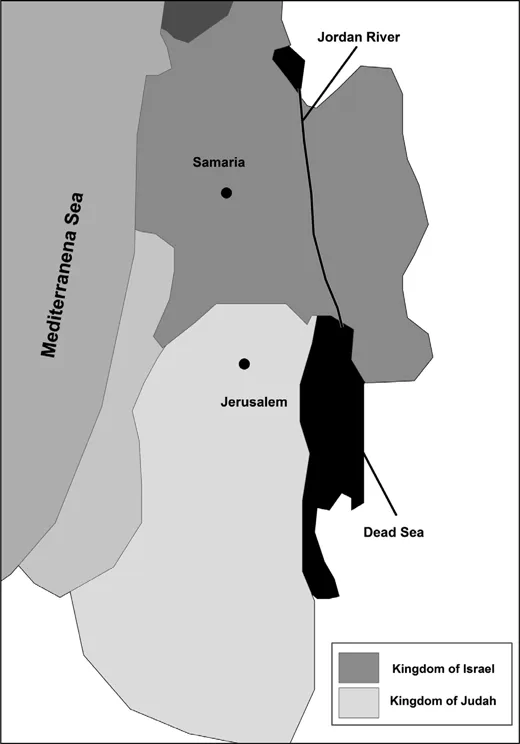

- —1025–926/925 b.c.e.: Israel created by Sol, David, Solomon

- —966–926/925 b.c.e.: Solomon builds Temple in Jerusalem for Ark of Covenant

- —722–586 b.c.e.: Israel conquered by Assyrians and Chaldeans

- —586 b.c.e.: Nebuchadnezzar destroys Jerusalem and Temple; Babylonian Captivity begins

- —586–200 b.c.e.: Jewish Bible, Tanakh, completed

- —164–64 b.c.e.: Maccabean rebellion leads to recreation of Israeli state

- —64 b.c.e.: Pompey conquers Palestine for Rome

- —37–4 b.c.e.: Herod the Great rebuilds Jerusalem and Second Temple

- —6–4 b.c.e.: Birth of Jesus (Joshua) of Nazareth

- —66–70 c.e. (Common Era): Jewish War and the Great Revolt leads to Roman destruction of Second Temple

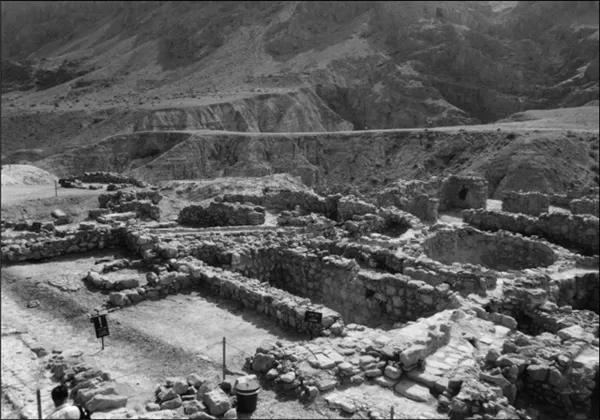

- —73 c.e.: Masada falls to Romans

- —70–100 c.e.: Christian Gospels written

- —132–135 c.e.: Bar Kochba rebellion

- —312–337 c.e.: Reign of Constantine the Great

- —325 c.e.: Council of Nicaea

- —354–430 c.e.: St. Augustine. Wrote City of God and Tractus adversus judaeos

- —476 c.e.: Traditional date for collapse of Western Roman Empire

- —527–565: Reign of Byzantine (Eastern Roman) emperor Justinian I. Corpus Iuris Civilis

- —768–814: Charlemagne

- —1095–1099: First Crusade and Christian conquest of Jerusalem

- —1147–1149: Second Crusade

- —1187–1192: Third Crusade

- —1135–1204: Moses Maimonides

- —1141: Jews accused of “ritual murder” in Norwich, England

- —1198–1216: Reign of Innocent III

- —1202–1204: Fourth Crusade

- —1290: Edward I expels Jews from England

- —1306: Jews expelled from France by Philip IV

- —1347–1351: Black Death

- —1492: Ferdinand and Isabella expel Jews from Spain

- —1517: Martin Luther writes his Ninety-five Theses

- —1543: Luther writes On the Jews and Their Lies and On Schem Hemphoras and the Lineage of Christ

- —1484–1531: Life of Protestant reformer Ulrich Zwingli

- —1508–1564: Life of Protestant reformer John Calvin

- —1553: Pope Julius III orders Italian Jews to live in ghettos

Jewish Beginnings

Exile and New Traditions of Faith

The Jews, Hellenism, and the Maccabean (Hasmonean) Rebellion

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Introduction

- 1 Jewish History: Ancient Beginnings and the Evolution of Christian Anti-Judaic Prejudice Through the Reformation

- 2 Jews, the Enlightenment, Emancipation, and the Rise of Racial Anti-Semitism Through the Early Twentieth Century

- 3 The World of Adolf Hitler, 1889–1933: War, Politics, and Anti-Semitism

- 4 The Nazis in Power, 1933–1939: Eugenics, Race, and Biology; Jews, the Handicapped, and the Roma

- 5 Nazi Germany at War, 1939–1941: “Euthanasia” and the Handicapped; Ghettos and Jews

- 6 The Invasion of the Soviet Union and the Path to the “Final Solution”

- 7 The “Final Solution,” 1941–1944: Death Camps and Experiments with Mass Murder

- 8 The Final Solution in Western Europe and the Nazi-Allied States

- 9 The Holocaust and the Role of Europe's Neutrals: Then and Now

- 10 Liberation, DPs, and the Search for Justice: War Crimes Investigations and Trials in Europe, the United States, and Israel

- 11 Historiography, Memorialization, and Lessons ‘Unlearned’

- Glossary

- Appendix A—Estimates of Jewish Deaths During the Holocaust

- Appendix B—Estimates of Roma Deaths During the Holocaust

- Appendix C—Yad Vashem: Righteous Among the Nations

- Appendix D—SS Ranks (Based on US Army Equivalents)

- Appendix E—German Army Ranks (Based on US Army Equivalents)

- Notes

- Index