eBook - ePub

Black Indians and Freedmen

The African Methodist Episcopal Church and Indigenous Americans, 1816-1916

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

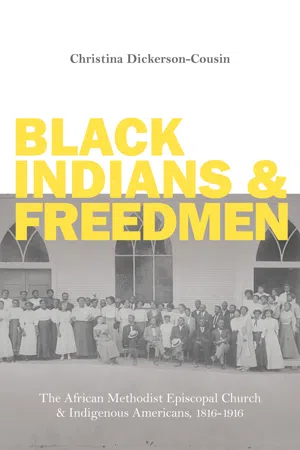

Black Indians and Freedmen

The African Methodist Episcopal Church and Indigenous Americans, 1816-1916

About this book

Often seen as ethnically monolithic, the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in fact successfully pursued evangelism among diverse communities of indigenous peoples and Black Indians. Christina Dickerson-Cousin tells the little-known story of the AME Church's work in Indian Territory, where African Methodists engaged with people from the Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Seminoles) and Black Indians from various ethnic backgrounds. These converts proved receptive to the historically Black church due to its traditions of self-government and resistance to white hegemony, and its strong support of their interests. The ministers, guided by the vision of a racially and ethnically inclusive Methodist institution, believed their denomination the best option for the marginalized people. Dickerson-Cousin also argues that the religious opportunities opened up by the AME Church throughout the West provided another impetus for Black migration.

Insightful and richly detailed, Black Indians and Freedmen illuminates how faith and empathy encouraged the unique interactions between two peoples.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Black Indians and Freedmen by Christina Dickerson-Cousin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic & Tribal Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Illinois PressYear

2021Print ISBN

9780252086250, 9780252044212eBook ISBN

97802520531771

Richard Allen, John Stewart, and Jarena Lee

Writing Indigenous Outreach into the DNA of the AME Church, 1816–1830

Though usually described as a Black religious body, the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, during its foundational development in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, identified with Native people. Perhaps, a fluid understanding of racial identity led early African Methodists to view Indigenous people, if not as brothers and sisters, then certainly as “cousins.” The disparate activities of Richard Allen, John Stewart, and Jarena Lee established a precedent for Native interactions, and these interactions affirmed an ethos of ethnic diversity within African Methodism. While an infrastructure for Indigenous evangelization and Atlantic expansion had not been developed, the individual initiatives of Allen, Stewart, and Lee set an important example for future African Methodists. Their efforts reveal an aspect of early AME history that scholars have underappreciated. Allen and his contemporaries viewed their denomination as one open not only to Black people but to all marginalized people of color. They displayed this intercultural openness by reaching out to Indigenous communities from the inception of the AME Church.

This discussion commences with Richard Allen, the founder and first elected and consecrated bishop of the AME Church. Though his general biography is well known, scholars have minimized the intercultural openness that characterized his early ministry. This openness had a profound effect on the development of the AME Church, making it into a religious venue that welcomed Indigenous people. Allen began his ministry in 1783, after purchasing his freedom from slave master Stokeley Sturgis. Even before his manumission, Allen, already an active Methodist, had attained a preaching license.1 From 1783 until 1785, Allen sojourned throughout the Middle Atlantic, the Chesapeake, and the Carolinas. During this time, he spent two months evangelizing among Native groups. Extant evidence reveals nothing about which groups he worked among.2 Nevertheless, Allen’s actions demonstrate that he viewed Native people as potential Methodists from the beginning of his ministerial career. He poured this perspective into the African Methodist Episcopal Church both before and after its formal founding in 1816.

Due to Allen’s foundational influence, AME ministers pursued outreach to Native communities during the 1820s and 1830s. In 1822, African Methodists sought out John Stewart, a Black man who had established the Methodist Episcopal Church’s (MEC) first permanent mission to Indigenous people. Stewart defected from the white denomination to join the AME Church because he recognized the institution as one that would embrace his work with Native people. Jarena Lee, the AME Church’s first authorized female preacher, emulated Allen and Stewart through her evangelization of Indigenous people in the 1820s and 1830s. Her efforts proved short lived because of an undeveloped denominational infrastructure. At the same time, African Methodists were also beginning their efforts in Haiti and Sierra Leone. All this work occurred during what Llewellyn Longfellow Berry, a historian of AME overseas expansion, called the “unorganized” period. During this time, which lasted from 1820 to 1864, motivated individuals carried out domestic and foreign missionary endeavors without consistent institutional support. It was not until 1864 that the AME Church established and funded a missionary department and elected a secretary of missions to oversee that department. Notwithstanding an absence of regularized operations for evangelistic outreach, an ethos of ethnic diversity informed AME identity.3

This chapter argues that Richard Allen, John Stewart, and Jarena Lee wrote Indigenous outreach into the very DNA of the AME Church. For their part, Native communities in the North welcomed Black religious personnel into their midst, interested to hear the Christian message espoused by other marginalized people. Scholars have not adequately acknowledged these experiences and have, therefore, underappreciated the extent to which Black and Native people built intercultural networks during the early republic period. These interactions between the AME Church and Indigenous communities occurred during the Second Great Awakening (C. 1795–1835), a religious movement that swept the nation and empowered Black evangelists, particularly from Methodist and Baptist denominations, to travel widely while preaching the Gospel. This chapter contributes to the historiography of the Second Great Awakening by illuminating unacknowledged examples of Black evangelists laboring among Native people.4

Richard Allen

Because of formative experiences during his early ministry, Richard Allen deliberately developed the AME Church into a sacred venue that welcomed Indigenous people. These formative experiences included his interactions with Native populations during the Revolutionary War, his friendship with Methodist evangelist Benjamin Abbott, and his two-month-long missionary project among Indigenous communities in the 1780s. Historians have failed to fully appreciate the role that these experiences played in Allen’s life and on the development of the AME Church. Charles H. Wesley’s landmark biography of Allen in 1935, Richard Allen, Apostle of Freedom, did not mention his interactions with Native people. In the 2008 book Freedom’s Prophet, another major Allen biography, Richard S. Newman discussed some of Allen’s experiences with Native people but did not analyze how these experiences shaped his perspective on African Methodism.5

Years before becoming a founder of the AME Church, Allen was an enslaved man living in Delaware with his master, Stokeley Sturgis. In 1777, while still enslaved, Allen became a Methodist. He was attracted to the young Methodist movement in large part because of its racial egalitarianism and the way that it reflected his understanding of the scripture. He recalled that the “Methodists were the first people that brought glad tidings to the colored people.”6 Methodist ministers genuinely sought out converts regardless of race or class, including Native people. In 1736, John Wesley himself performed his first evangelizing efforts in the Americas among Indigenous groups including the Yamacraw in Georgia. Wesley’s brief but consequential experiences allowed him to conceive of a Christianity that was accessible to everyone and devoid of Anglican pretentions.7

Allen’s early years as a Methodist coincided with the Revolutionary War, and during this time his labors brought him into contact with Native people. Allen recalled that he was “employed in driving of wagon in time of the Continental war, in drawing salt from Rehoboth, Sussex County, in Delaware.”8 He delivered the salt to various locations throughout Pennsylvania, including General George Washington’s army encampment at Valley Forge. The Continental Army remained at Valley Forge from December 1777 until June 1778, and Allen’s salt deliveries were critical for preserving the soldiers’ meat rations. During his visits to Valley Forge, Allen was exposed to Native people from the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy.9 He might have met the Mohawk leader Atiatoharongwen. Also called Louis Cook, Atiatoharongwen had an Abenaki mother and an African father, but was adopted by the Mohawk at the Jesuit mission of Kahnawake. During the Revolutionary War, Atiatoharongwen fought alongside the Continental Army and was present at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777–78. Allen also might have interacted with any of the roughly fifty Oneida warriors who arrived at Valley Forge in May 1778. Allen regularly preached on the route to and from his salt deliveries. His exposure to Native people at Valley Forge compelled him to contemplate their role in his ministry.10

After the Revolutionary War, Allen obtained his freedom and became an itinerant preacher. He soon developed a friendship with Benjamin Abbott, a prolific Methodist minister. His relationship with Abbott, coupled with his experiences at Valley Forge, pushed Allen to view Native people as potential Methodists. Abbott was born in 1732, became a Methodist in 1772, and evangelized in New Jersey, Maryland, and other locations until his death in 1796.11 Allen first met Abbott in New Jersey during the spring of 1784. Allen spent significant time with the patriarchal preacher and attended several of his evangelistic engagements. He marveled that, “[Abbott] seldom preached but what there were souls added to his labor.” Allen concluded that Abbott was “one of the greatest men that ever I was acquainted with” and described him as “a friend and father to me.”12 Abbott is the only religious figure whom Allen described with such effusive language and with whom he formed a fictive kinship bond. Historians have not sufficiently examined the significance of Allen and Abbott’s relationship. This relationship was crucial, however, in demonstrating to Allen that racial egalitarianism was central to the Methodist movement and that Native people must be included within it.13

Abbott regularly preached to racially diverse audiences that included Indigenous people. While in New Jersey he accepted an invitation to visit a mixed Black and Native Congregationalist meeting.14 The worshippers responded enthusiastically to Abbott’s preaching: “many fell to the floor; some cried aloud for mercy, and others clapped their hands for joy, shouting, Glory to God! so that the noise might have been heard afar off.”15 This experience led Abbott to conclude, as the apostle Peter had in the Book of Acts, that “God is no respecter of persons; but all those who fear him and work righteousness, of every nation are accepted of him.”16 The members of the interracial congregation were so impressed by Abbott that many of them followed him to his next preaching appointment. On another occasion, Abbott recalled a meeting during which “three Indian women [professed] justification in Christ Jesus.” He also encountered an “old Indian woman” who sought his interpretation of a religious experience she had undergone. Abbott assured her that she was saved and that “God would do greater things for her yet.”17 Abbott’s commitment to creating a multiracial Christian community that included Native people inspired Allen’s reverence for him.

Abbott refused to tolerate the bigotry that he saw some Methodists display toward Indigenous individuals. Near Cape May, New Jersey, he met with a Methodist congregation that was attempting to expel a mixed-race Native man. Abbott explained that “some of them, having more pride than religion, could not stoop to sit in class with him; and to cloke [sic] the matter a little. They had raised several objections against him, and without supporting anything, insisted on my expelling him.” Abbott, after observing the man’s good character, refused to oblige the discontented white Methodists. Two of them were so offended that they quit the congregation. Abbott accepted their departure and crossed their names off the list of church members. In his view, their racial intolerance was incompatible with Methodism, and he preferred to lose their membership rather than compromise his beliefs.18

Allen probably remained in contact with Abbott throughout the 1780s and the 1790s, each man reinforcing the other’s belief in the racially inclusive message of Methodism. Given their close familial relationship, Allen was surely aware of Abbott’s continued efforts among Native populations. These efforts encouraged Allen to view Indigenous people as potential converts. Moreover, Allen’s relationship with Abbott made the segregationist and exclusionary behavior of other white Methodists that he encountered all the more jarring.19

After Allen’s experiences at Valley Forge and the development of his relationship with Abbott, sometime between 1783 and 1785 he devoted two months to evangelizing among Native communities himself.20 Extant evidence gives no indication of which people he visited, but perhaps they were Haudenosaunee like those who had encamped at Valley Forge. Whatever groups he met would have had similar stories of war and land loss. The 1783 Peace of Paris, the treaties that ended the Revolutionary War, brought catastrophe for Indigenous nations regardless of which side they had supported. As Ethan A. Schmidt explains in Native Americans in the American Revolution, “whether they sided with the British, the Americans, or attempted to maintain neutrality, the Peace of Paris left them to the mercy of land-hungry settlers who moved quickly to appropriate native land and disrupt their cultural, political, and economic systems.”21 Allen’s visits in the 1780s would have exposed him to communities struggling to maintain their sovereignty and their territory. To them, he might have preached that the same God who had seen him through his “bitter” days of slavery would sustain them through their painful and perilous experiences.22

Allen’s interactions with Native people did not end after his two-month sojourn. In the late 1780s, Allen had sustained contact with an Indigenous man, Israel Tolman (Tallman), whom he hired as an indentured servant. Newman first brought attention to this relationship in Freedom’s Prophet.23 Tolman was born in Allentown, Pennsylvania, around 1773 and was the son of a white man and an Indigenous woman. Allen employed him in his chimney sweeping business in Philadelphia, probably as a part of his general effort to hire people of color and teach them marketable trades. It is possible that Tolman shared aspects of his Indigenous culture with Allen. It is also possible that Allen, drawing on his previous experiences with Native people, attempted to convert Tolman. Around August 1788, Tolman ran away from Allen, breaking his indenture contract. Newman surmised that Tolman fled to escape “the drudgery of chimney sweeping” and Allen’s “fearsome work ethic.”24 Allen ran two advertisements in the Pennsylvania Gazette, offering a four-dollar reward for the return of Tolman. These advertisements were evidently unsuccessful.25

By 1787, Allen’s accumulated experiences had shown him that the Methodist movement embraced all people, whether they were Black, white, or Indigenous. His view changed after an ugly and transformative incident in St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. He had been preaching to Black congregants at the church for over a year when white Methodists became discomfited by their growing presence. One Sunday morning in November 1787, church trustee...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on Terminology

- Introduction: The Drums of Nonnemontubbi

- 1 Richard Allen, John Stewart, and Jarena Lee: Writing Indigenous Outreach into the DNA of the AME Church, 1816–1830

- 2 Seeking Their Cousins: The AME Ministries of Thomas Sunrise and John Hall, 1850–1896

- 3 The African Methodist Migration and the All-Black Town Movement

- 4 “Ham Began … to Evangelize Japheth”: The Birth of African Methodism in Indian Territory

- 5 “Blazing Out the Way”: The Ministers of the Indian Mission Annual Conference

- 6 Conferences, Churches, Schools, and Publications: Creating an AME Church Infrastructure in Indian Territory

- 7 “All the Rights … of Citizens”: African Methodists and the Dawes Commission

- Notes

- Index