- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cultural Studies Vol 18 1 Jan 2

About this book

Cultural Studies examines how cultural practices relate to everyday life, history, knowledge, ideology, economy, politics, technology and the environment. Volume 18 from the 2nd January 2014.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cultural Studies Vol 18 1 Jan 2 by Various Authors in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

REREADING DAVID MORLEY’S THE ‘NATIONWIDE’ AUDIENCE

DOI: 10.4324/9781003209324-4

This article intends to revisit David Morley’s work, The ‘Nationwide’ Audience: Structure and Decoding, by reanalysing his findings in a way of revealing some distinct decoding patterns. While The ‘Nationwide’ Audience has been acclaimed as one of the most influential empirical works in audience studies, it has been often misunderstood as if the work Jailed to find out systemic and consistent influences of viewers’ social conditions on decoding practices. On the contrary, by using a statistical method, this paper demonstrates that the audiences’ decodings of the programme presented by Morley are in fact clearly patterned by their social positions. The findings reveal the over-determined effects of various social conditions such as class, gender, race and age. Particularly, the results seem to restore the importance of social class on the interpretive process, which has been displaced and ignored in many current media studies. Highlighting audiences’ structural social positions, the reading patterns rediscovered here allow us to rebut not only the traditional Marxist view of class determinism but also any relativist accounts of cultural activity.

KEYWORDS: The ‘Nationwide’ Audience, David Morley, audience studies, encoding/decoding, decoding position, cultural studies

David Morley’s book The ‘Nationwide’ Audience (henceforth NWA) has been acknowledged as one of the most influential works in the emergence and development of the new audience research (Turner 1990, p. 131, Corner 1991, p. 269, Lewis 1991, p. 59, Seiter 1999, p. 15). The NWA work as a prominent representative of the ‘first generation’ of critical audience research (Alasuutari 1999, p. 4) has provided theoretical and empirical insights into the multifaceted relations between media texts and audiences for the last two decades.1 However, the findings of NWA have been misrepresented so widely without rigorous scrutiny that some significant findings about audience interpretations have remained veiled. By reanalysing NWA, this essay intends to rectify these misunderstandings and redeploy the theoretical implications of NWA for the decoding process.

Any discussion of NWA must begin by recognizing the significant influence of Stuart Hall’s essay ‘Encoding and decoding’ (1980), originally published in 1974, on which NWA is theoretically grounded.2 By placing encoding and decoding as distinctive but related processes with their own conditions of existence, Hall opened up a new theoretical space for signifying struggles built on the premise of ‘no necessary correspondence between encoding and decoding’. Central to the model stands the concept of ‘preferred meaning’, which refers to the dominant meanings encoded in a text, which ‘can attempt to “prefer” but cannot prescribe or guarantee’ the viewer’s decoding (Hall 1980, p. 135). In relation to the concept of ‘preferred meaning’, he describes three hypothetical decoding positions – ‘hegemonic-dominant, negotiated and oppositional decoding’ – resulting from the inflection of viewers’ social conditions of existence. According to Morley (1980, 1992), Hall’s three decoding positions stem from Frank Parkins’ idea of the relationship between meaning systems and class position, but Hall does not limit the sets of power relations to class.

In testing Hall’s encoding/decoding model, Morley started with a detailed textual analysis of the Nationwide television news magazine programme so as to elucidate the basic codes of meanings and implicit ideologies inscribed in the text.3 Then, Morley investigated in NWA decoding processes as an encounter between two determining forces: that is, on the one hand, the preferred meanings of a text, and, on the other hand, viewers’ social positions infused with certain kinds of discourses and experiences (Morley 1992, p. 119). The hypothesis of NWA was that decodings would vary with viewers’ basic socio-demographic factors (i.e. age, sex, race and class), their involvement in various forms of cultural frameworks and identifications at the levels of formal and informal structure and institutions (e.g. trade unions, sections of the education system and subcultures), and with topics of texts (Morley 1980, p. 26). Considering audiences as socially structured and clustered groups, Morley differentiated his project from uses and gratifications research, which assumes that audiences are comprised of individuals abstracted from the social structure. Thus, paying particular attention to their various social positions, he sampled 227 people in 29 groups who lived mainly in London and in the Midlands region, and interviewed them after showing two programmes of Nationwide.

Misunderstandings of NWA

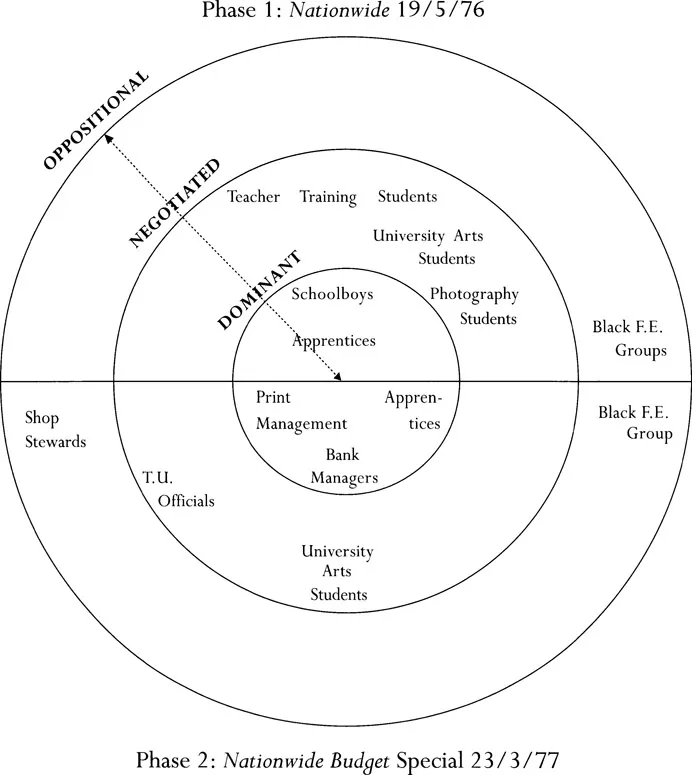

Based on the results from the NWA project, Morley argued that ‘the difference in decodings between the groups from the different categories is far greater than the level of difference and variation within the groups’ from the same categories (1980, p. 33). However, he did not seem to succeed in providing a clear picture of patterns of reading mainly because he did not represent the findings in a systematic and easy way to compare viewers’ decoding positions with their various social conditions. As figure 1 shows below, some group labels focusing on their occupations such as ‘apprentices’ or ‘bank managers’ mainly indicate the class position of the group members, while the ‘black FE group’ label their race position. As a result, the most common misevaluation of NWA has been that the study failed to show any distinctive reading patterns in relation to audiences’ social positions to the extent that some subsequent researchers have accused NWA of providing a theoretical justification for the celebratory notion of empowering audiences (e.g. Modleski 1991, p. 38).4 For instance, Turner argues in his well known book, British Cultural Studies:

It is not surprising that Morley fails to achieve this goal [tracing the shared orientations of individual readers to specific factors] in The ‘Nationwide’ Audience; many would hold that the ‘specific factors’ (class, occupation, locality, ethnicity … and so on) are so many and so interrelated that even the attempt to make definitive empirical connections is a waste of time. […] It is clear … that the attempt to tie differential readings to gross social and class determinants, such as the audiences’ occupation, was a failure.(1990, pp. 132–133, p. 135)

This critique of NWA often replicates the inaccurate understanding of Hall’s ‘Encoding/Decoding’. For example, Turner (1990) says, ‘Its [‘Encoding/Decoding’] inference that different readings might be the product of audience members’ different class positions had proved to be particularly contentious’ (p. 132, emphasis added). Fiske also argues: ‘What Morley found was that Hall had overemphasized the role of class in the production of semiotic difference and had underestimated the variety of readings that could be made’ (1987, p. 268, emphasis added). But Hall (1980) never confined the meaning of social positions into social class in his ‘Encoding/Decoding’ essay since he rejected the idea of economic determinism in the decoding model. Morley himself clarifies that: ‘Indeed, it is some of my own early formulations, rather than Hall’s, that give such distinct analytical priority to class, over and above all other social categories’ (1992, p. 12).5 In fact, Morley reduced the meaning of ‘social positions’ into ‘class position’, as he noted in the conclusion of NWA:

Thus, social position in no way directly correlates with decodings – the apprentice groups, the trade union/shop stewards groups and the black F.E. [further education] student groups all share a common class position, but their decodings are inflected in different directions by the influence of the discourses and institutions in which they are situated.(1980, p. 137, emphasis added)

This reduction inhibited Morley himself from excavating the influence of other social factors such as gender, race, and age on decoding. In addition, the word ‘in no way directly correlates’ makes his results look ambiguous. None the less, it cannot be said that his special attention to social class as a significant factor on decoding was misguided. In the following section, I attempt to demonstrate that social positions correlate with decodings and that social class is a very important factor in the interpretation of a text, which Morley impressively found but himself did not fully realize.

A udiences’ social positions and decoding

Programme phase 1

Table 1 compiles Morley’s findings of the viewers’ d...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Editorial Statement Page

- Contents Page

- Genetic Kinship

- Media Advocates, Latino Citizens and Niche Cable: the Limits of ‘No Limits’tv

- Pornography in Small Places and Other Spaces

- Rereading David Morley’s the ‘Nationwide’ Audience

- The Couch and the Clinic: the Cultural Authority of Popular Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis

- Notes on contributors

- Notes for contributors