- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cardiac Ultrasound

About this book

From its humble beginnings in the 1950's as an adaptation of marine sonar systems, echocardiography has recently grown rapidly in its usage and importance. Advanced computer techniques now allow imaging of the heart in many planes through many 'windows'. Each section of this book contains all forms of ultrasound imaging including transesophageal (TOE), intra-operative, epicardial and intravascular as well as the more standard types. The book's purpose is to improve diagnosis of cardiac disease through the use of the latest echocardiographic methods of investigation. It is of use to physicians in training and in practice, to technicians and radiologists interested in ultrasound.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cardiac Ultrasound by Leonard Shapiro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Cardiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

BASIC PHYSICS

DOI: 10.1201/9781315138800-1

Sound travels in waves. Frequency, the number of waves per unit time, is measured in Hertz (Hz) with 1 Hz representing 1 cycle per second. The wavelength is inversely proportional to the frequency. Ultrasound is high frequency sound waves above the range that is detected by the human ear. Frequencies of 1.5-7.5 MHz are used in echocardiography and the wavelength at 1.5 MHz is approximately 1.0 mm. The speed of sound in soft tissues such as the heart is 1540 m/s. There is a trade-off between transducer frequency and penetration; higher frequency sound waves give better resolution, but have poor penetration. In adult echocardiography, therefore, a lower frequency transducer is used, which allows imaging of deep structures; higher frequency transducers are used more for pediatric imaging.

When ultrasound travels through tissue, a certain proportion is reflected back to the transducer at interfaces between tissues of different acoustic impedance such as the interface between blood and heart valves or myocardial tissue. Ultrasound is generated by the piezoelectric effect. An electrical charge is applied across a piezoelectric crystal. This causes deformation of the crystal, which oscillates at a predetermined frequency which is dependent on its thickness. To image the heart through the relatively small acoustic windows, a transducer which creates a fan of ultrasound and sector-shaped image is employed. The ultrasound fan typically contains 120 scan lines, each of which is produced by sending a pulse down that line; the reflected echos from that line are then collected. The same transducer is used both to transmit and to receive the ultrasound.

A mechanical or electronic method may be used to steer ultrasound pulses down the individual scan lines. Mechanical transducers employ either rotating or oscillatory systems. Electronic beam steering is achieved using phased array technology. The crystal element of the transducer is divided into 64 or 128 individual elements, each with its own electronic connection. Each element is fired and the individual wavefronts merge to form a compound wave. Steering direction is determined by the sequence in which elements are fired. Phased array technology is more reliable than mechanical as the beam is steered without using moving parts; it also allows superior beam focusing. A disadvantage of phased array transducers is the near field artifact caused by ‘side lobes’ which are off-axis ultrasound beams formed by interaction between individual elements. Annular array transducers combine features of both mechanical and phased array technology. The beam is steered mechanically but individual elements are fired in sequence as in phased array transducers which allows narrow beam formation and improved resolution.

Principles of Doppler

Doppler echocardiography is based on the Doppler effect, first described by the Austrian physicist Johann Doppler in 1842. The principle describes the change in frequency in sound waves caused by the motion of the source or the observer. In cross-sectional echocardiography, we are interested in sound waves reflected from boundaries of solid structures such as the walls of cavities, the valves, and pericardium. In Doppler echocardiography, the interest is in sound reflected back from red blood cells. The frequency of sound reflected back from red blood cells is compared to that of emitted sound. The difference in frequency between emitted and returning ultrasound is the ‘Doppler shift’. If the reflected sound has a higher frequency than the emitted sound, the Doppler shift is positive and this signifies flow towards the transducer. If the reflected sound is lower in frequency, it is termed a negative Doppler shift, and represents flow away from the transducer. The Doppler equation relates the Doppler shift to the velocity of red blood cell flow:

- Δf = Doppler shift

- f = frequency of transmitted sound

- ν = velocity of red blood cells

- θ = angle between blood flow and direction of ultrasound beam

- c = velocity of sound

The direction of ultrasound must therefore be parallel to the direction of blood flow for measurement of absolute blood velocity. Lesser degrees of alignment will result in underestimation of velocity.

Spectral Doppler display uses variations in gray scale to indicate different intensities in returned Doppler signals according to the number of red blood cells travelling at each velocity. Flow towards the transducer is, by convention, displayed above a horizontal axis and flow away from the transducer is shown below the line. There are three modes of Doppler currently in use: pulsed Doppler, continuous-wave Doppler, and color-flow mapping.

In pulsed Doppler the transducer alternates between emitting and receiving pulses of ultra-sound. Blood flow at a specific area of the heart can be examined by placing a sample volume at that site. The transducer emits a pulse and then waits for the returning signals from that site before transmitting the next pulse. The equipment is calibrated to analyze ultrasound returning only from that area of interest. The maximum velocity that can be detected by pulsed Doppler is limited, as velocities are sampled by pulses rather than continuously. The Nyquist limit is a term which defines the maximum velocity that can be measured. Measurement of frequency shift and hence velocities requires a pulse repetition rate of at least twice the Doppler frequency shift of the sampled area. If the Nyquist limit is exceeded, then the phenomenon of aliasing occurs. The sampling rate is too low to detect the high velocity, which is cut off and displayed in the opposite direction on the spectral display. Aliasing may occur to an extent where high velocities are wrapped around the display several times. The Nyquist limit is dependent on the pulse repetition frequency (higher when the sample volume is nearer the transducer and the distance for ultrasound to travel is less) and the frequency of the transducer. Aliasing will occur at higher velocities for lower frequency transducers.

In continuous-wave Doppler the transducer has two elements, one continuously emitting ultrasound and the other continuously detecting the reflected sound waves. The pulse repetition frequency, therefore, is infinite and there is no limit on the velocity which can be measured. However, as velocities are measured along the whole length of the beam there is no spatial resolution.

Pulsed and continuous-wave Doppler are complementary techniques. Pulsed Doppler allows high spatial resolution, but cannot measure high velocities. It is better for discriminating between laminar and turbulent flow as the spectral trace is narrow, whereas with continuous-wave Doppler velocities are measured along the length of the beam and there is spectral broadening. Continuous-wave Doppler can measure high velocities, but there is no spatial resolution. In normal hearts most blood flow velocities are <1.5 m/s and can be measured by pulsed Doppler. In disease states velocities are often high and continuous-wave Doppler techniques are necessary.

Color flow mapping may be superimposed on cross-sectional or M-mode images. It is a pulsed Doppler technique where blood velocity and direction data are sampled down a number of scan lines The various velocities are color-coded and displayed by velocity and direction in relation to the transducer. Normal flow towards the transducer is depicted as dull shades of red, with normal flow away from the transducer in blue. As it is a pulsed Doppler technique it has the same limitation in terms of inability to measure high velocities as pulsed Doppler. When aliasing occurs the colors become brighter and a mosaic appearance occurs.

2 THE NORMAL HEART

DOI: 10.1201/9781315138800-2

Standard Transthoracic Imaging Planes

Although there is an infinite number of possible imaging planes The American Society of Echo-cardiography has defined a series of standardized imaging views. These standard imaging planes are designated on the basis of:

- Transducer location.

- Spatial orientation of the imaging plane.

- Structures recorded.

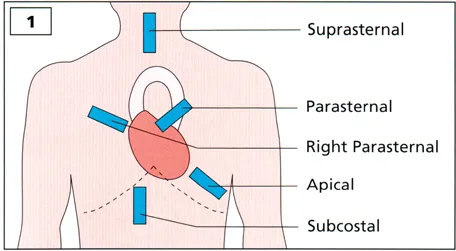

They employ parasternal, apical, subcostal and suprasternal windows. In 1 the transducer positions employed in echocardiography are illustrated diagrammatically.

Parasternal long-axis images with corresponding line drawings

The parasternal long axis view of the left heart is obtained by placing the transducer on the left sternal edge, choosing an intercostal space that will align the interventricular septum perpendicular to the transducer. This plane transects the heart from the aortic root through both leaflets of the mitral valve and the body of the left ventricle. This plane is ideally suited to evaluate the anterior right ventricular free wall and right ventricular cavity, the aortic root, aortic valve, left atrium, mitral valve, and body of the left ventricle, but not the apex. The function of the anterobasal portion of the interventricular septum and posterior wall may be observed. This view is unsuitable for quantitative Doppler examination of mitral valve flow and left ventricular outflow as the Doppler beam is perpendicular to the direction of flow. Mitral and aortic regurgitation however may be detected, as the regurgitant jets may be eccentric.

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents Page

- Foreword Page

- Preface Page

- Acknowledgments Page

- Abbreviations Page

- 1. Basic Physics

- 2. The Normal Heart

- 3. Rheumatic Mitral Valve Disease

- 4. Non-Rheumatic Mitral Valve Disease

- 5. Mitral Valve Replacement

- 6. Aortic Valve Disease

- 7. Aortic Valve Replacement

- 8. Sub- and Supra-Aortic Stenosis

- 9. Tricuspid Valve Disease

- 10. Infective Endocarditis

- 11. Cardiac Masses

- 12. Pericardial Disease

- 13. Thoracic Aortic Dissection

- 14. Coronary Artery Disease

- 15. Cardiomyopathies

- 16. Sinus of Valsalva Aneurysm

- 17. Congenital Heart Disease

- Index