- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

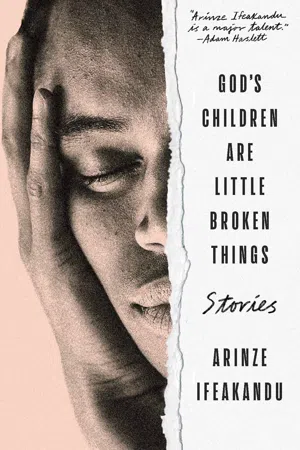

God's Children Are Little Broken Things

About this book

***Finalist for the 2022 Kirkus Prize for Fiction***

***Longlisted for the 2023 Dylan Thomas Prize***

In nine exhilarating stories of queer love in contemporary Nigeria, God’s Children Are Little Broken Things announces the arrival of a daring new voice in fiction.

A man revisits the university campus where he lost his first love, aware now of what he couldn’t understand then. A young musician rises to fame at the price of pieces of himself, and the man who loves him. Arinze Ifeakandu explores with tenderness and grace the fundamental question of the heart: can deep love and hope be sustained in spite of the dominant expectations of society, and great adversity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access God's Children Are Little Broken Things by Arinze Ifeakandu in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

WHAT THE SINGERS SAY ABOUT LOVE

I.

I’d seen Kayode once before, in first year, having a bath downstairs, his wet body an assemblage of small perfect muscles, his ass firm and flawless, his dick, my God. I noticed him in the way that one notices something beautiful but unattainable and did not see him again until second year, when I went with my friend Ekene to a campus celebrities’ bash. He was going from group to group, talking, swaying to the music, and I only recognized him as someone I’d seen before but did not know, until I heard someone say his name. Ekene had talked about him a few times in the past, this handsome boy who made beautiful music. I sat in a corner of the room, watching people dancing, thinking how happy their lives were in that moment, how tomorrow this senseless joy would be absent. His eyes caught mine watching him. He looked puzzled, a look that, with most boys, usually turned into aggression. I glanced away.

When I looked back up, he was staring at me. I smiled, unsure of how to read and return that brazen stare. He smiled back, whispered something to a girl who was deep in conversation with Ekene, and she nodded, a quick, distracted nod. He strode toward me, holding a can of Star, which he placed on the table as he sat opposite me. I noticed, for the first time, the tiny gleaming silver stud in his right ear.

You seem to be having so much fun, he said, smiling. He had the whitest teeth.

You’re teasing me, I said.

Oh no, I’m not, he said, lifting his arms innocently, and for a moment I believed him, but then he smiled widely and asked, Why aren’t you dancing?

I can’t dance, I said, shrugged.

He arched his eyebrow. The song playing now was loud, was full of clanging metal, of booming drums, and the dancers had gone completely mad, jumping and shaking their heads like people about to burst into incantations. When he spoke, he had to shout: Everybody can dance.

Not me, I said. I dance like a girl.

You what?

He leaned in and I leaned in, my lips to his ear. His hair had a distant scent, of something sweet and fruity. I imagined him in the bathroom, his head crowned in lather. Then I remembered his body, the muscles moving across his back and arms as he washed himself vigorously, and I felt a little guilty; it had been different seeing him down there among a dozen other boys having their baths outside as I brushed my teeth, each person a feature of morning, now it seemed like a small violation.

I dance like a girl, I said into his ear.

He looked at me weird. You dance like a girl, and so? he said, squeezed his face thoughtfully. Standing up, he held out his hand. What, I said, confused and a little excited, and he said, Trust me, smiling a playful-wicked smile. He led me to the middle of the room where he started swaying his shoulders. God, Kayode, I said, covering my face with my hands. Love me, love me, love me, the speakers boomed, and he sang along, holding out his hands toward me, so ma fi mi si le / Oh I like it here.

A girl laughed, yelled, Dance!

Dance, someone else responded, and soon it was a chant, Dance! Dance! Dance!

You see? Kayode said, taking my hands and twirling me round. God, kill me now, I thought, and moved my hips. Yes, people cheered, and if not for these shouts of affirmation, I might have collapsed from the exposure. Closing my eyes, I let the music take hold of my body, waves of pleasure rippling through me. This was what people meant when they said dancing was fun, I thought, this absolute surrender. When the music stopped, I opened my eyes, and there was Kayode beaming, Ekene cheering, the dance floor drowned by laughter and applause. I shook Kayode’s hand and he pulled me into a manly hug, our shoulders clashing.

I need some air, I said, as the next song began.

God, me too, he said.

He followed me to the balcony, where a few people had carved a space for themselves to smoke and talk. The street below was dark, electric poles watching over the closed shops, and there was some breeze, and the music blasting inside was muffled, Kayode having shut the door behind us. I took a dramatic breath, saying how good the air was on my face. I felt happy yet anxious and exposed, a confusing meld: I’d noticed a few guys leave when Kayode led me to the dance floor, now I was sure that they’d left in disgust and anger, those had to be the only reasons.

I have to go home, I said.

He looked puzzled, concerned. Are you okay?

Yes, I said. I’m just not a party person. I’m exhausted already, but I’m glad you made me dance.

It made my night, he said, eyes alight, and then looked at me serious. I should probably see you off. You don’t want to jam bad guys walking alone, this is their time.

I texted Ekene: Walking home with Kayode. See you tomorrow, hun. We walked downstairs and out the gate together, down the dusty road, the houses gray and forlorn.

So how come you know my name? he said. I was a bit surprised when you said it on the dance floor.

I glanced at him; walking side by side, I noticed I was taller. You’re kind of famous, mister.

He laughed. You know, I used to see you in the hostel. I would think to myself, Who is that guy, I have to know his name.

I felt a small, sweet stirring in my chest. Why didn’t you talk to me? I asked.

Because you always had this unfriendly look on your face, and you walk really fast.

He looked serious; I laughed, slowing down my steps. He laughed, too. At Hilltop Gate, a group of guys were seated on the corridor of a closed shop, smoking weed, and I reminded myself to put on my manly walk and my manly face. He called out to them, My manchi, and they called back, Baba, and I felt terribly grateful for his presence. We walked out of the gate, making small talk, little rocks crunching under our sneakers, onto Cartwright, the tarred roads illuminated by lights beaming from hostel windows. We walked toward the senior staff quarters, took the thin path leading to the boys’ quarters, the ground a carpet of dead leaves. At my door, I said, Thank you, and he said, Yeah, sure, and looked at his feet and then at my face, a peculiar shyness rising into his eyes.

He was naked in my bed the next morning and almost every morning until the end of semester. For the first week, we stayed indoors all evening and fucked like two freshers newly discovering the joys of having a room away from home, stepping out only to buy food or get a change of clothes for him or more condoms from the chemist at Hilltop Gate.

Little things made him happy, such as my neighbor’s singing, which was horrible (it sounded like a billy goat in heat, he said) but joyful, or the fact that I snored after a long day (or a long night, he added). We would be quiet one minute and the next he would shatter in laughter, flashing his phone, This is fucking hilarious, and it would be the most mundane thing.

When he was away at his lectures, or playing the occasional weekend gig in Enugu, and I was alone, I pressed his clothes to my face, thinking, This is a dream.

The holidays came and went—I traveled to Kano while Kayode returned to Ibadan, and we texted during the day and talked all night on the phone, his voice husky with need as he said, I cannot wait to hold you again, I go die on top your body—and soon it was November and the harmattan wind began to blow, ripping off rusty-old roofs, covering windows and furniture in dust. At first the trees were bare, their branches spread out and dry; later, they caught pink and purple fire, abloom. Kayode bought a big mattress, and we threw out my old one, which was slim and almost flat. He wore the thickest sweaters, the cold made him sick, and if he could miss a class, he did, so that I returned home many afternoons to find him curled under the blanket, either asleep or typing into his phone. When he was well enough to attend classes, he went with two or three handkerchiefs, because he was that sort of person: his clothes (jeans, T-shirts, ankara, whatever, really) were crisply ironed and spotless. Who are you kitting for? I teased him often.

For you na, he’d say. Abi you don’t like me looking good?

And he would spread his arms and turn around, putting on such a show, I’d fall back on the bed, weakened by laughter.

I spent most of my evenings bent over my table, at war with quantum chemistry, which I loathed, and he spent his with his headphones on, hunched over his laptop, bopping his head. One evening, he let out a triumphant yelp, and I knew he’d cooked a beat he liked. I looked up from my book to stare at him. Sorry, he said.

Let me hear it.

I eased into bed beside him. He placed the headphones over my head, his arm wrapped around my shoulders. The beats filled my ears, bass strong and booming, drums understated but with a distinct, swinging movement, guitar lines joyful yet sad; it made me think of lovers at a beach, of the sun setting, of warmth and tranquillity. This was a love song, no doubt.

I’ve never heard anything like this, Kayo.

You like it? His face was bright with optimism, with expectation. How could one ever say no to that face, to those tenderly childlike eyes?

Of course, I do, I said. It’s like you found a new, more mature voice and yet retained the best parts of you.

He stared at me, as though unbelieving. Somto, he said, and then he grabbed my face and kissed me. He hugged me so tight, it almost hurt. I love you. God, I love you so much.

There had been other boys before Kayode. There had been Basil in first year, terribly cute Basil who had a girlfriend and said he wasn’t gay but loved getting his dick sucked by me but would never suck dick himself because, hey, he wasn’t gay. Before Basil, there had been Uzo, a customer at the warehouse where I worked after graduating secondary school, Uzo with his I love you and I use to drive Toyota Corolla, Uzo who was thirty-two and said he loved me, even though I was just seventeen, who said No need for condom, you’re my only one and I am your only one, except, he was my only one, the other half was utter bullshit, a truth I learned the hard way trying to explain to my parents why I had sores there. Two trips ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- The Dreamer’s Litany

- Happy is a Doing Word

- Where The Heart Sleeps

- God’s Children Are Little Broken Things

- Alọbam

- Good Intentions

- What The Singers Say About Love

- Michael’s Possessions

- Mother’s Love

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author