This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 258 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

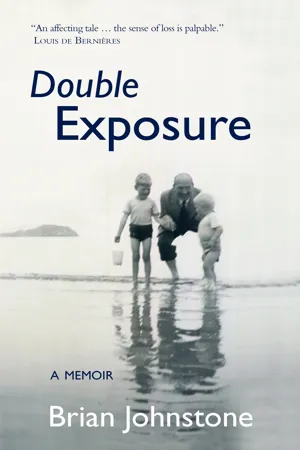

Double Exposure

About this book

Two revelations, each coming to light 20 years apart following the deaths of his father and mother, prompt Brian Johnstone to turn a poet's eye on his 1950s childhood and explore his parents' lives before and during World War II. His double set of discoveries lead him to encounter relatives both forgotten and unknown, to free an elderly cousin from the burden of a secret kept for a lifetime, and to forge an enduring relationship with the half-sister he never knew he had. In a memoir sure to resonate with baby-boomers and anyone who has lost and found unknown relatives, Brian ponders why he was never trusted with the truth and vividly evokes a post-war upbringing, under whose conventional surface so much was hidden.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Double Exposure by Brian Johnstone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

After the Tone

It was close to midnight when I got home one cold October night in the penultimate year of the twentieth century. The phone was bleeping when I came in, its light flashing to indicate a new message. On other nights that late, I would have left it to deal with in the morning. But the final event of our brand new festival had finished that evening, so, hoping that it might be a message of congratulations, I pressed play and waited for the anticipated, ‘Well done!’ or ‘Great start!’

Nothing could have prepared me for what I heard. The now obsolete mini-cassette tape has long since been wiped and the aged phone disposed of, but it went something like this:

I’m ringing as I think you are the son of the late Mrs Beatrice Johnstone of Morningside in Edinburgh. If not, please disregard this message. But if you are, you might be interested to know that her daughter, your half-sister Maria, is in Scotland just now. And she’s trying to contact you. This is her husband speaking – she feels too emotional to call you herself. So, please do ring me back on this number if you would like to get in touch?

That was followed by a landline number whose area code I didn’t recognise. Then came the long bleak tone of a phone hung up. And silence.

I have no memory at all of what I did next. But I vividly recall those moments – returning home after the success of our new-founded festival, the answerphone bleeping, and my utter astonishment at the message. The half-sister to whom the message referred was someone I had never heard of, had no inkling even existed. But what made the message even more shocking was the memories it brought back, the past perplexities it evoked.

What I do remember is what I did subsequently – although due to the late hour, not until the following day. It was then that I called my brother to discuss the situation. Relaying the phone message had a similar effect on him. The two of us were amazed. The content of the message – the revelation of this half-sister – was extraordinary, uncanny even. But its means of delivery was astonishing too.

‘What a weird way to get in touch with news like that,’ my brother said. ‘It’s earth-shattering.’

‘Don’t you think,’ I suggested, ‘it would’ve been a bit more sensitive just to say some information about an unknown family member had turned up?’

‘Sure – then the guy could’ve waited until we’d made contact before revealing what his news was all about.’

How many people, we wondered, would choose to leave such a highly charged piece of information as a phone message?

‘Actually, wouldn’t a letter have been more appropriate?’ I said. ‘My address is in the phone book, after all.’

What I could not know then was the assumption behind the chosen means of communication. In fact, as I discovered later, the phone message had been left in the belief that I would already know about this half-sister. This was not the case. I had no idea whatsoever that such a person existed. Neither did my brother. But she and her husband had no means of knowing that.

* * *

My mother – the Beatrice Johnstone referred to in the phone message – had died aged eighty-five, the previous March. A woman of very definite opinions, she would not have reacted well to her full Christian name being used. Christened Beatrice for one of her grandmothers, who had died tragically young, my mother always loathed the name and had never used it. She had also dropped the diminutive Beattie decades back. It had been the name of her childhood and youth, which she had long since shortened further to Bea – the name by which all of her adult friends had always known her. And the name that my father – who had also instigated a change, from the ‘Tom’ of his youth, to the ‘Gilbert’ of his mature years – clearly preferred for his wife.

But, just over six months earlier, I had registered her death. This had required the use of her full name.

At the time, both my brother and I were still rather raw from mourning our loss. As well as that, the last year or two of my mother’s life had been something of an emotional rough ride. Her health had been breaking down – difficult for anyone – but more so for a sport-obsessed woman who had been fit all her life. She was also exhausted by her recent removal from the suburban Edinburgh family home where she had lived alone since our father’s death twenty-two years before.

Fiercely independent for as long as we could remember, Bea had resisted all suggestions that the house was too much for her. As she entered her eighties, my brother and I were becoming increasingly concerned that the two-storey end terrace Edwardian villa, to which we had moved in 1957 and where we had spent most of our childhood, was becoming more and more of a burden.

This is a situation familiar to most people with elderly parents: a desire to see the parent maintain independence, but offset by a concern that they should still be able to cope, still enjoy the same independence without any excessive additional risk. That dilemma can weigh heavily on the next generation of family members and can so easily give rise to resentment – even distrust – on the part of the aged parent.

At family gatherings – Christmas, Mum’s birthday, visits from relatives and the like – my brother and I would choose the moment to head for another room and have anxious discussions about her future.

‘How can we persuade her it really is time for a move?’ we would wonder. ‘And how can we get her to see this won’t be the end of her independence?’

Leaving Bea in the sitting room chatting with our wives or playing with my brother’s children, we used to think we would never be disturbed. But no matter how many cups of tea or glasses of sherry we plied her with, it never worked.

We would pretend we had only been trying to wash the dishes or make a fresh pot of tea; that we were admiring my brother’s new car or taking a look at something in the garden. We would say all we needed was to get some air. But it was no good. Our mother would seek us out with cries of, ‘I just know you’re talking about me! I won’t have you discussing me behind my back. Stop it at once!’

We never did get far with these sessions. Perhaps Bea’s wartime work with the Air Ministry had made her extra alert. Maybe she was suspicious by nature. Perhaps older parents develop a sixth sense as to when they are the subject of discussion. Or maybe this had derived from similar experiences earlier in her life – there would have been many of those.

In vain, we tried to reassure our mother that we were only thinking of her, only looking after her interests. Yet she was fully aware it was her life we were attempting to redirect. And she was determined to resist it. The conflict was clear. We could plan all we wanted, but getting Bea to agree to anything – that was always going to be the biggest step.

Various plans were mooted. But nothing as drastic as a care home. We imagined our mother in a small flat of her own, maintaining her independence. We had our own ideas as to how this could be accomplished. But she was insistent she would never countenance one suggestion we made – splitting the family home into two apartments, the lower of which she would retain. So the best option seemed to be sheltered housing – somewhere with a manager on site in case of emergencies. And she was ideally placed for it. Just around the corner from her house was a new block of such flats, recently built in ‘the field’ – a patch of wasteground we had played in as boys. Bea would not even have to move to another part of town. And, by way of a bonus, this block was even closer to her beloved golf course.

But, was she to be persuaded? She was not. Getting her to accept advice from her own children was well-nigh impossible. The family home meant too much to her. As did making her own decisions.

‘It’s the house I bought with Gilbert, which we shared for years,’ she said. ‘I owe it to your Dad to keep it – and to keep up the garden’. So much of her past – her identity even – was tied up with the family home.

But a resolution came more quickly than we expected. Behind all her resistance, my mother was becoming aware of how many difficulties her deteriorating health was causing to her household routine.

The family home was absurdly large for her needs. The sole occupant of a kitchen and scullery, two public rooms and five bedrooms, she now lived in just three of those. Although the large lounge was brought into use for a week each Christmas, it and the other surplus spaces were chilly and uninviting for most of the year. Much of the furniture was immediately post-war in style – several pieces still boasted the Utility mark – and all were heavy and cumbersome. But each item had to be moved for cleaning and, she insisted, replaced on the exact same spot. To do otherwise would reveal the wear marks on the equally aging carpets. There was room after room to hoover – or ‘vac’, as she’d have said. Acres of woodwork to dust – doors and skirting boards, mantelshelves, windowsills and her much admired pitch-pine staircase. Countless surfaces to polish – the dining table and sideboard, the cocktail cabinet, the spare bedroom furniture – all unused for most of the year, but requiring her special touch, her personal attention. Appearances had to be kept up.

The look of the old place was also breaking down. It was beginning to be an embarrassment. Rhones were springing leaks and downpipes were rusting. The garden was rapidly getting beyond her. As someone with such exacting standards, she would, if she could, pick up every fallen leaf that strayed into the flower beds and religiously remove every weed that dared to show face.

Indoors, it was the same. Curtains were fraying to such an extent that to draw them any way other than gingerly was to risk the fabric coming away in your hand. Her favourite royal blue stair carpet was wearing out – I found her one day inking in the bald patches with matching biro. The bathroom cistern was such a problem that visitors had to be shown the precise way to pull the chain. Failure to get this right – and there were many – caused a continuous stream to debouch into the lavatory bowl.

But she was reluctant to spend money on any replacements, knowing how much the sheer scale of the undertaking would cost. Having already coped with dry rot – the blame for which she always laid at the door of her slovenly neighbour – she was unable to face any further disruption. The plaster dust from the dry rot repairs was too awful a memory. It haunted her. Still present in the fine film she could not help noticing on all her polished surfaces, its residue was apparent even years after the event – or so she claimed.

On one occasion, towards the end of her time in the old house, I suggested getting some new flooring for the kitchen. But it was no use – she was adamant that the lino would ‘see her out’.

‘It’s not that old! It was only laid in ’57 – when we moved in,’ she reminded me, ‘It’ll do for ages yet.’

It was a relief, therefore – but really no surprise – when she announced to us that she was going to move into the very block of flats my brother and I had spotted some time before. And it was a decision, she was adamant, she had made entirely by herself.

‘I was chatting to a friend from church the other day,’ Mum let slip, almost casually, ‘and she told me one of the flats round the corner was on the market. It’s very nice in there, she said – so I’ve been to have a look. Anyway, I’ve had a good think about it and I’ve decided to put in an offer.’

A neat way of avoiding having to accept our advice – or at least of having to admit to it. But it was her decision – that was important. We had no grounds for complaint. The move was on.

Her offer accepted, our mother was happy for my brother and me to organise the work on the new flat – as long as she had final say on the colour scheme. But it was impossible to persuade her to relinquish any of the tasks involved in the sale of the family home. As a former legal secretary, she had more experience than either of us. Before long she impressed us both by advertising the old house in the Edinburgh property supplements, conducting a series of viewings and making her decision as to who the new owners would be.

To her credit, she decided to accept a lower offer on the place so that a family with young children could be the new occupants.

‘This was always a family home,’ she explained, ‘and I’d like it to be one once again.’

* * *

My brother had been closely caught up in dealing with the breakdown of our mother’s health. He was still living in Edinburgh, only ten minutes up the road from Bea, while I was based in Fife, an hour or so away to the north. However, I was more directly involved in her removal from the family home. I had taken a year off from my teaching post to write. My first collection of poems having been recently published, a follow-up was uppermost in my mind. However, I was rapidly dragooned into organising the house clearance and the preparation of the new flat. Since to her way of thinking I was ‘not working’, my mother deemed me available to help her sort through the detritus of forty years under the same roof. Down-to-earth as ever, she was unable to consider my writing as work.

We talked a lot during the long hours of sorting and sifting, but then, we always had. While I was keen to avoid the hole-by-hole, shot-by-shot accounts of her almost daily games of golf, I was happy to chat with Bea about all sorts of other topics. We would talk regularly on the phone – often having hour-long calls when she would give me full accounts of her life day-to-day – but she was always ready to listen to what I’d been getting up to. She much preferred, though, to hear about the goings-on at the various schools I worked in and my life in the teaching profession than about any of my activities in the literary world. I think she worried she might not understand these. The necessity of grasping a topic straight away was something she was emphatic about. She would shy away from talk of poetry or books, art or music fearing always that she would be out of her depth in those areas.

One of her many received opinions was that to talk knowledgeably with ‘the male of the species’ – something she always prided herself on being able to do well – a woman had to have a good understanding of ‘what is going on in the world’, a workaday grasp of current affairs. This she undoubtedly had. But she tended, latterly, to be about three weeks to a month out of date. In her desire to get her money’s worth out of every newspaper, she would read them cover to cover and, in her later years, would get somewhat behind in keeping up. Still, she was always happy to discuss the state of the country – largely terrible, she thought – while we went for long walks in the summer, or runs in my car in the winter. Very much typical of her class and generation, her opinions were never the most progressive and I frequently found myself challenging them. Even so, she was always ready to argue a point and even, on occasion, to concede one.

Most of our chats during the house clearance, though, were about the past – her past – prompted, on occasion, by the contents of unidentified boxes or discoveries at the back of cupboards. Having kept an almost obsessively tidy house – a trait I do not share – I was discovering my mother’s aptitude as a hoarder – a trait that I do share.

Battling over bits of string that ‘might come in handy’ was trying. Getting shot of the contents of a long obsolete coal bunker was a struggle. And persuading her to part with her collect...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Introduction

- Prologue

- 1 After the Tone

- 2 Adults & Betters

- 3 Four of a Family

- 4 The Way She Told Them

- 5 Crossing a Line

- 6 Once Bitten

- 7 Letters Sent & Unsent

- 8 Mum's the Word

- 9 Twice Shy

- 10 Most Unusual

- 11 In Love or Otherwise

- 12 Dates Changed & Unchanged

- 13 Maintaining the Fiction

- 14 Continental Drift

- 15 Shouting the Odds

- 16 Too Late Now

- 17 To Whom It May Concern

- 18 Anything Like a Story

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author