![]()

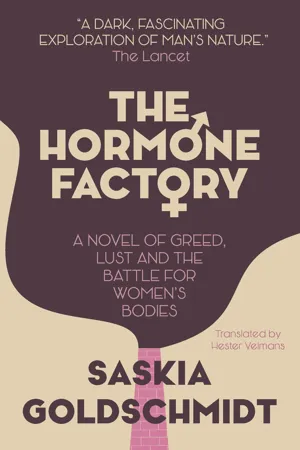

Saskia Goldschmidt

Translated from the Dutch

by Hester Velmans

![]()

1

Day by day I seem to be sinking more deeply into the gloom that has characterized so much of my time on earth. I know them well, the days when it feels as if you’re stuck ankle-deep in filthy, glutinous sludge and even the slightest movement demands just too much effort. The hours you lie in bed motionless because you’re locked in a cocoon of wretchedness. It’s from that supine position that you survey the world. The sun that rises and shines, as if its light could possibly make any difference. Mizie entering the room with her mirthless smile. The hustle and bustle of people in the street, as if their comings and goings made the world even one jot better or worse. Yes, for years I operated under the same delusions. Ah, how I believed that I mattered, that with my abilities, my determination, my intelligence, I would make the world a better place! And I have left my mark, that’s true. But whether it’s helped the world—who the devil knows? Out of the frying pan and into the fire, that’s all it ever amounts to, for every damn one of us.

Way back when, even in the darkest days of my depression, I always knew I’d eventually emerge from my cocoon, that I’d reconnect with the world and dive back into the fray. And I didn’t do it half-assed; I was one of the winners. Ever since Darwin, we’ve known that it’s either eat or be eaten. I always was a contender. But in the final analysis, all that striving has left me with just a single insight, and that is that none of it matters. Whether you’re the winner or loser, perpetrator or victim, it doesn’t make a damn bit of difference.

I have now come to accept that this time I won’t escape. This is the end, the godforsaken final chapter. And how I long to turn my back on this madhouse, to breathe my last! I’m done for, finished, and high time too!

* * *

But death is a heartless thing; first it goes for the tender morsels. The reckless kid leaping on his motorbike only to crash headlong into a lorry, the fat sow in her fully automatic Volkswagen stalling in the middle of a railway crossing, the young mother blissfully giving birth only to realize once the labour is over what a risky business it is to pop such a frail little bundle out into the world. In the prime of life, that’s when death likes to get them.

But a tough old geezer on his deathbed like me it prefers to ignore. Endlessly putting off the time of departure.

I am still complete master of my mental faculties, which, like some cruel joke, make me exquisitely aware of each and every physical debility. Damn this body, slave to so many uncontrollable urges! The bodily functions are packing it in one by one, like lab rats being used to test something that leaves them belly-up in their cages gasping for air. The pain keeps getting worse and the reprieve of sleep grows ever more elusive.

![]()

2

Ezra has been arrested, the silly fool. Mizie has tried to hide it from me, but the young thing assisting her with my mortifying care left her newspaper behind. Front-page news. Well, that’s par for the course. A total lack of self-control, right at the most critical juncture in his life. That boy never did know where to stop. In his passions, his ambitions, his drive, and his physical needs. Always hungry for more. Whether it’s food, attention, power, or sex, he never can have enough. The fear of being overlooked, of missing out, was in him from the moment his mother gave birth to him. The fate of being the youngest in the family. Having to fight for attention right from the start.

The greed with which that child latched on to his mother’s breast—it was something I’d never seen in any of the others. He drained her from the word go. He was so rough with her, the little monkey, so determined to suck his mother dry to the last drop that she howled in pain. His toothless mouth clamped on her nipple and refused to let go, no matter how loud she screamed. A little monster, he was, our youngest. Rivka, who had always taken pleasure in nursing her brood, gave up on him soon enough. He devoured her very peace of mind, that boy, he just sapped too much of her energy and lifeblood. One day I came home unexpectedly, catching her unawares. There she sat, gripping the bottle, a struggling Ezra in her lap. The boy, all red in the face from howling, kept trying to grab her breast, safely tucked away inside her copious bra and black lace blouse. A flushed Rivka had Ezra in a stranglehold and was attempting to force the flaccid rubber nipple into his mouth; he immediately spat it out again in disgust. He always did have good taste, my youngest. When she saw me she began to cry.

“Mordechai, this child, this cuckoo in the nest—I’ve tried, but I can’t. I breast-fed all four of the little girls with love. But this devil child—I can’t take it anymore, you deal with him!”

She hurled the bottle across the room, thrust the screeching infant into my arms, and fled the room in tears. I had come home to change before leaving for London for an important meeting to secure our foreign interests. It was February 1939, and this was promising to be a mammoth session, one that would almost certainly end with a lavish dinner to celebrate a successful outcome. For when I negotiate, I keep at it until I’ve struck a great deal; I won’t stop until it’s done.

I carried the boy to the office—we lived next door to the factory—and ordered Agnes, my willing, discreet, and smooth-tongued secretary, to fetch Alie Mosterd. I knew she was suckling another little tyke. She worked in packaging and her family was always struggling to make ends meet, so a little extra income was bound to come in handy. It was soon settled. Alie would nurse the boy for five guilders per month plus a weekly food parcel, including all the necessary vitamins and minerals. Not to mention free supplements for her entire family. Five guilders was an enormous sum; in those days a litre of horse piss cost me only four and a half cents. But hey, you can’t feed a baby on horse piss, and problems are for the solving. If anyone deserved a little extra, it was Alie. A sweet girl, healthy too; didn’t smoke, didn’t drink, always punctual, had started working here as a young girl. She’d begun to look a bit run-down, however. Her husband worked in our warehouse and was reliable, a simple but decent fellow. With her, Ezra would be in good hands. We arranged that she’d come and give the boy five feedings a day. That would take the pressure off Rivka. I had our little girls to think of too, after all. They didn’t need a mother suffering from nervous exhaustion, and I didn’t need a wife who wouldn’t stop blubbering. We’d see if it was still necessary in a few months’ time, once the boy was ready for solid food. I asked Agnes to please inform Rivka of the arrangement after she had calmed down a bit. Then I changed my clothes in a hurry and got to the airport just in time to catch my plane to London. Getting things done pronto, that’s always been my forte.

![]()

3

Speed is my middle name, unlike my twin brother, Aaron, who was always slowness incarnate. He was stuck in first gear all his life, whereas I was always stepping on the gas, shifting from neutral to sixth in the blink of an eye. Getting ahead, that’s what life’s all about. Aaron just didn’t have it in him. Whether it was school, or women, or self-preservation, he always seemed to be two steps behind. When we were kids, I’d take to my heels as soon as a gang of Catholic scum started coming after us, but Aaron would freeze like a petrified rabbit in the headlights. I can’t tell you how many times I had to rescue him from the clutches of his Christian persecutors. Except for that last time, years later, when I failed to save him. Although I could have, if he hadn’t been so goddamn stubborn. It was that fanatical rectitude of his, trumping every instinct for survival. I’m not one to let my conscience bother me; it was Aaron’s moral principles that sent him toppling into the abyss. As if we weren’t all animals—eat or be eaten. Not to speak ill of the dead, but Aaron was a loser his entire life.

* * *

I threw myself wholeheartedly into the competitive fray. Those were the days; it was a time when we were constantly coming up with one scientific breakthrough after another. It was an incredibly exciting struggle that never let up—to be the first, to crush the competition, to outsmart the best in the world day in, day out. And were we ever good at it!

Without blowing my own trumpet, I can safely say that in this nation of wusses, this swamp pit of small-minded burghers who look down their noses at dreamers, I was one of the first to realize that commerce needs science, and vice versa. To run a successful meatpacking operation is one thing: it takes skill and business savvy. But to get further ahead, you have to have guts; you have to use your head and dream big. My father plucked my brother and me from school and got us started in the meat business. He wouldn’t let us go to university, and the thought of it still makes me fume. Shit, how I’d have loved to be allowed to study—I’d have chosen chemistry, naturally, which I consider the most fascinating of all subjects. There’s nothing finer than knowing how to analyse and then purify some substance, to synthesize the compounds it consists of, and so to unravel nature’s mysteries. To contribute to man’s mastery over matter, that was my burning ambition as a young man. But it was out of the question. I had to join the firm.

“You are a De Paauw,” said my father, “and De Paauws don’t have time for egghead tomfoolery. You can’t live off your brains; brains won’t bring in a cent—unless you’re making headcheese or sausage, of course. Butchering, meat production, that’s what’s in our blood, we’ve never done aught else, and oughtn’t to aspire to anything more either. There’s no other meatpacker in these parts that’s got a more sterling reputation than ours.”

And although I’m no pushover, I never was able to stand up to my father. I was afraid of him, as were most people. You should have seen Aaron—he’d start shaking whenever my father called for him. He’d begin to stutter, which is why he never earned my father’s respect, which did eventually come to me. Bringing Aaron into the firm was a farce. My brother was such a softy that he tended to screw up every transaction. But he could not, would not, disappoint my father, so he stayed on, a stone around our necks, while never, not even for a single day, being happy there. Lived only for others his entire life, did what was expected of him, his loyalty offered to all mankind. And right when he finally has a chance to start over—he gets trampled to death under the great scumbag’s storm-trooper boots. No idea why my brother keeps popping up in my mind. Haven’t thought much about him in years. Best that way too. Crying over spilled milk doesn’t get you anywhere. What’s done is done, there’s nothing you can do about death’s unpredictable ways.

* * *

While we were trainees in our father’s business, I kept a low profile, ostensibly meek and subservient like Aaron. Meanwhile I was eagerly taking in everything that went on, both within the firm and outside, for as I’ve often said, an inward-looking company will miss the boat. Navel-gazing has never been a productive tactic in business. To get somewhere you have to dare to break new ground, you have to dare to dream. And to stick your neck out; if you don’t take any risks you’re never going to get off the ground.

When my father passed away and at age twenty-seven I took over as head of the firm, with Aaron (heaven help us!) as my deputy, I immediately swung into action.

It was the early nineteen-twenties, and we were processing two thousand pigs and three-fifty head of cattle a day. We produced sausages, hams, and smoked meats, as well as bacon and gammon for the English market. Blood and bone meal went into fertilizer; we had a refinery for fats and oils and, last but not least, a soap factory. The hog bristles were used to manufacture brushes. We extracted value from every scrap of animal corpse, from head to hoof. Except for those dratted organs. There was nothing you could do with them. No one could give me a reason why every animal was stuffed to the gills with those weird gummy parts. What damn use were they? Darwin had taught me that everything on earth that’s alive exists for a reason, or it would have become obsolete or extinct long ago. But in our predominantly Roman Catholic regi...