- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The first social history of disability and difference in American adoption, from the Progressive Era to the end of the twentieth century.

Disability and child welfare, together and apart, are major concerns in American society. Today, about 125,000 children in foster care are eligible and waiting for adoption, and while many children wait more than two years to be adopted, children with disabilities wait even longer. In Familial Fitness, Sandra M. Sufian uncovers how disability operates as a fundamental category in the making of the American family, tracing major shifts in policy, practice, and attitudes about the adoptability of disabled children over the course of the twentieth century.

Chronicling the long, complex history of disability, Familial Fitness explores how notions and practices of adoption have—and haven't—accommodated disability, and how the language of risk enters into that complicated relationship. We see how the field of adoption moved from widely excluding children with disabilities in the early twentieth century to partially including them at its close. As Sufian traces this historical process, she examines the forces that shaped, and continue to shape, access to the social institution of family and invites readers to rethink the meaning of family itself.

Disability and child welfare, together and apart, are major concerns in American society. Today, about 125,000 children in foster care are eligible and waiting for adoption, and while many children wait more than two years to be adopted, children with disabilities wait even longer. In Familial Fitness, Sandra M. Sufian uncovers how disability operates as a fundamental category in the making of the American family, tracing major shifts in policy, practice, and attitudes about the adoptability of disabled children over the course of the twentieth century.

Chronicling the long, complex history of disability, Familial Fitness explores how notions and practices of adoption have—and haven't—accommodated disability, and how the language of risk enters into that complicated relationship. We see how the field of adoption moved from widely excluding children with disabilities in the early twentieth century to partially including them at its close. As Sufian traces this historical process, she examines the forces that shaped, and continue to shape, access to the social institution of family and invites readers to rethink the meaning of family itself.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Familial Fitness by Sandra M. Sufian in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2022Print ISBN

9780226808703, 9780226808536eBook ISBN

9780226808673PART I

Expecting Normality: 1918–1955

CHAPTER ONE

Exclusionary Practices in the Age of Eugenics and Child Welfare

Writing in 1922, Honoré Willsie, a women’s magazine editor and adoptive mother, recalled that suggesting to her spouse to adopt “conjured up a horrid picture of discomfort, of responsibility, and of risk.”1 Those considering adoption and those working in adoption saw the venture as full of hazards and risks. Florence Clothier, a key commentator on adoption and a psychiatrist at the New England Home for Little Wanderers, warned in 1942: “There is risk in adopting a child and there is risk in being adopted . . . we can struggle ceaselessly to minimize them [risks].”2 Clothier conceded that although agency adoption would “remain a hazardous relationship,” it was much less dangerous for children than the usual alternative of living in an orphanage.3 Clothier’s words typify the social work attempt to minimize and avoid risk in adoption, from the early decades of the twentieth century through World War II.

According to Clothier, social workers and parents based their feelings about adoption’s danger on the recognition that there was a grave responsibility in placing a defenseless child with unrelated parents for life.4 As much as permanence in a family was social workers’ goal for children without permanent homes, it was also fraught with serious reasons for hesitation. The motivated act of placement in adoption—in contrast to the inability to choose to have a biological child—increased public and professional fears about it.

Adoption professionals who discussed risk certainly included social and legal factors, but by far they focused most on the risk of disability. There is not one moment, or one piece of evidence, when it is clear that professional social workers “discovered” the question of disability and adoption. However, collective concerns about the interface of disability and adoption—both conceptually and materially—permeate the practices of American agency adoption from the Progressive Era until the end of World War II.5 Adoption workers believed it had a strong potential—if not outright inevitability—to jeopardize the integrity of family formation.

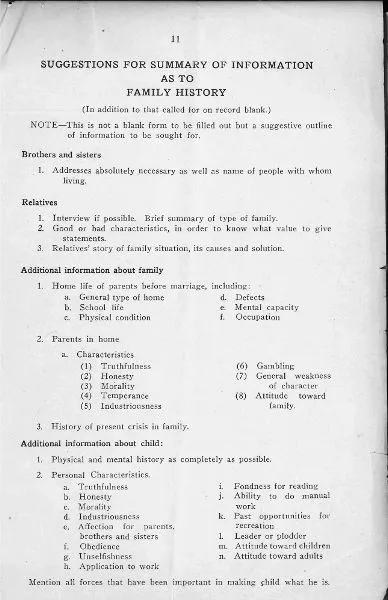

FIGURE 1. Suggestions for Summary of Information as to Family History. From Bureau of Children, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Welfare, “The Significance of Children’s Records,” Bulletin No. 32 (February 1928). CWLA Collection, Box 56 Folder: Admin Recording 1928, Social Welfare History Archives.

This judgment was based on numerous assumptions about disability and about families. Adoption professionals believed that even the placement of children with suspicious heredity would likely fail because adoptive parents would judge a child as damaged. These practitioners concluded that taking in a child with a problematic heredity or body was an obvious and avoidable risk of adoption.6 Some practitioners believed that placing a child considered handicapped “by mental defect or bodily disability” was unjust to the adoptive family and the child because adoptive parents might return children who they felt “did not fit in.”7 They worried that parents would be constantly dissatisfied with a disabled child, which would result in the adoption falling apart.8

Practitioners’ worries that including a disabled child would lead to a problematic or even unraveled placement were not altogether unfounded. Given that prevailing expert and public attitudes supported institutionalizing children with “mental defects,” and that communal supports for adoptive families with disabled children were poorly lacking, adoption workers rationalized that it did not make sense to place a disabled child in an adoptive home when parents would likely remove her to a custodial setting.9

Adoption workers implemented casework investigation, physical and mental testing, and infant observation to achieve lasting adoptions and obviate ones they suspected would not last. Strategies in adoption to create certain families and to discourage others were conceptually and practically two sides of the same coin; they closely resemble eugenic ideologies around biological reproduction and highlight how eugenics itself was a flexible ideology and a set of practices that was adaptable to numerous social formations. Indeed, by employing eugenic tenets and goals about family-making in the 1920s and 1930s and integrating them into their investigation, testing, and observation practices, many adoption professionals effectively treated adoption as an alternative form of reproduction that closely aligned with eugenic goals relating to biological reproduction.10 They delineated which children were suitable for adoption as a way to achieve their primary task: to find the “right home for the right child” and to create adoptive families that were likely to be stable and enduring.11 But discerning which children to place to create a normal family and which to avoid was not straightforward, especially because the standards for adoption, including on child eligibility, were only vaguely outlined as late as 1938.12 Furthermore, many factors—like the definitional parameters of what constituted normal and abnormal; child welfare notions about proper American childhood; larger societal, medical, and economic developments; and prospective parents’ views—all themselves in flux, shaped the contours of child eligibility.

Fundamentally, adoption professionals strove to guarantee a healthy, nondisabled, suitable child for prospective adoptive parents as a way to mirror what they imagined was a “normal” biological family.13 Their model for such a family was rooted in what child welfare reformers imagined an ideal biological family to be. A complex set of variables and a larger narrative involving the regulation of adoption, the professionalization of social work, and the making of twentieth-century childhood structure this entanglement, but the zeitgeist of both eugenics and child welfare ideology about normality played particularly key roles in formulating child eligibility. Indeed, these two conceptual frameworks and their practical implementation jointly prevented the disabled child from being adopted in agency practice during this time.14

Eugenics is generally defined as the modern science of selective breeding for the betterment of society. But within different historical periods, there were “competing and evolving varieties of eugenics,” thus pointing to eugenics as a flexible ideology and as a set of practices with multiple permutations.15 As historian Paul Lombardo has argued, eugenics “borrowed meaning from the social and political agendas of the people who found practical uses for it no less than from those who first offered it as an idea.”16 Whatever their leaning, users of eugenic ideas shared the propensity to biologize social problems along the axes of race, gender, class, and disability and to prioritize concerns about reproduction and the family.17 Influenced by scientific racism, eugenicists believed that essential biological differences existed between white Protestant American-born middle- and upper-class citizens and people of other races and classes. They eschewed investments to improve the living conditions of the poor and of people with disabilities because they believed in a deterministic view of heredity; as such, they saw any investment to ensure improved conditions as a waste of time, effort, and money. Eugenicists argued that policies promoting the propagation of superior groups and the hindrance of inferior groups would help rid the country of its stubborn social problems.18

Eugenic understandings of disability (which included a variety of impairments but also alleged questionable heredity) as undesirable, risky, different, and defective, with a strong emphasis upon normality, played prominent roles in underpinning, fortifying, and cementing exclusionary agency practices.19 Using eugenic notions about difference, defectiveness, and especially (ab)normality, adoption professionals during this period employed a discourse of “disability risk” to discuss children’s desirability and to build adoptive families. These practitioners conceptualized disability risk as embodied and individualized, yet also group-affiliated; risk was intrinsic to the child yet collectively attached to the marginalized group of children with disabilities. Disability risk as an embodied peril essentially replicated operative ideas about disability itself, as a (medicalized) problem located in the individual that resulted in suffering, incapacity, and inferiority.

Child welfare and adoption professionals of the time seemed to think of disability risk as static, objective, and self-evident. To them, disability predicted an undesirable future.20 On this they concurred: disabled children had limited or even “tragic futures” that would burden, overwhelm, and cause adoptive parents to reject them. They saw this outcome as desirable for neither the child nor the parent. Putting aside whether such negative imputations about disability were just or accurate, adoption professionals applied these standard ideas to the practical issue of adoptability, the term they used to denote child eligibility for adoptive placement. They feared that the presence of disability would inevitably pose a significant risk to adoptive parents’ ability to build and sustain their family. What most professionals failed to weigh—or perhaps saw as outside their purview—was that the unadoptable label severely constrained the trajectory of a child’s life, producing the very “tragic future” it predicted. The label determined where the child resided, what opportunities she had, the scope of her social relations, and even whether she survived.

To understand how and why disabled children were excluded from agency adoption, we need to first examine modern adoption in the Progressive Era, during which time the landscape of adoption grew from a patchwork of haphazard practices to a field in which professional social workers began to standardize agency work. From the Progressive Era and through World War II—and much like their counterparts in other social work spheres—adoption professionals continued to refine the field’s principles and tools, to systematize adoption practices.21 Within that set of efforts, they articulated inclusionary and exclusionary child eligibility criteria in which the discourse of disability risk played a key part, and which ultimately negatively affected disabled children. Throughout this process, ideas from eugenics and child welfare about the normal child, the defective child, and the normal family pervaded the logics of a developing normative adoption practice.

Child Welfare Reform and Adoption

One of the transformative nodes that introduced the subject of adoption eligibility occurred even before the Progressive Era, with the 1851 Massachusetts adoption law. The law stressed the welfare of the child as a primary adoption concern and posited the importance of evaluating adopters’ qualifications. It instituted judicial supervision of adoption, directing judges to ensure that adoptions were “fit and proper.” It did not mandate or delineate the processes by which the state should place a child in a new family, however.22 In the absence of such legal direction, unsupervised private adoption agencies emerged. They were primarily run by philanthropic, sometimes religious, amateur women volunteers. Newly trained professionalizing social workers at the turn of the century scrutinized these agencies and were loath to accept them. Their criticisms reflected a larger paradigm shift in social work that moved from a practice based on individual moral judgments to one based on organized practice wisdom.23

Professionalizing social workers were working within an era marked by reform on a number of societal issues that responded to industrialization and urbanization, including poverty, harsh working conditions, public health, and child welfare. Reformers were also extremely distressed about public dependency among poor children.24 Towards the end of the nineteenth century, orphanages and almshouses served most dependent children whose parents could not care for them. The conditions in these institutions were terrible. Progressive Era reformers harshly criticized the moral failures of these institutions, yet they also held the newfound belief that the family could rehabilitate dependent children. These two dynamics led to the home-finding movement, where charity organizations preferred to “place-out” “normal needy and homeless” children in foster homes, boarding care, and adoption instead of in child-caring institutions.25 Even though Progressive Era reformers tried to offer alternatives to orphanages, dependent children’s institutionalization between 1900 and 1930 nearly doubled; in 1928, for instance, approximately 250,000 children were being cared for outside of their biological homes.26

During this time, a “dependent child” denoted one under seventeen years of age who received economic and social assistance from outside of the family. Child welfare workers commonly considered these children “victim[s] of various calamities, social deficiencies, or parental failures.”27 The dependent child category included children deserted by their parents, needy or neglected children (children born to poor, immoral, criminal, diseased, or feebleminded parents), abandoned babies, orphans, delinquents, and defectives. On the other hand, Progressive Era ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Abbreviations

- A Note on Language

- introduction. Disability and Belonging in Adoption History

- part i. Expecting Normality: 1918–1955

- part ii. Working toward Inclusion: 1955–1980

- part iii. Continued Obstacles: 1980–1997

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix 1. Suitability of the Child for Adoption

- Appendix 2. Chronology of Relevant Federal Bills and Their Provisions

- Appendix 3. Handicapping Conditions of Children Listed on Adoption Exchanges in 1985

- List of Archives

- Notes

- Index