- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Relaying Cinema in Midcentury Iran investigates how the cultural translation of cinema has been shaped by the physical translation of its ephemera. Kaveh Askari examines film circulation and its effect on Iranian film culture in the period before foreign studios established official distribution channels and Iran became a notable site of world cinema. This transcultural history draws on cross-archival comparison of films, distributor memos, licensing contracts, advertising schemes, and audio recordings. Askari meticulously tracks the fragile and sometimes forgotten material of film as it circulated through the Middle East into Iran and shows how this material was rerouted, reengineered, and reimagined in the process.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Relaying Cinema in Midcentury Iran by Kaveh Askari in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

An Afterlife for Junk Prints

It would make for a much simpler history had each newly released serial film or silent feature circulated provincially and globally with speed and uniformity. But the physical realities of film prints moving across trade borders and through intermediary institutions such as international exchanges and government censorship bureaus create messy periodizations. Quite frankly, the boundaries between early cinema and later film cultures are far more permeable than we have assumed. Their characteristics overlap in ways that warrant more focused attention. In a very general sense, any study of distribution attends to the intermediary life of film, but the speed and directness of film circulation vary enormously from region to region. In places that differ widely from general trends, the effect is not so much a local film culture lagging behind the production centers as a film culture out of sync. Rather than thinking about interruptions to circulation and damage to prints as incomplete steps toward more developed national film cultures, I want to consider how silent film’s cultural translation can be shaped by the conditions of its physical translation.

Silent cinema in the Middle East and North Africa offers standout cases. The strategies of global distribution of films established in the 1910s suffered greatly diminished successes in many cities across the Middle East and North Africa. With some important exceptions, many of the predominant film export businesses considered markets in the Middle East as less accessible or as failed opportunities by the late 1910s. American firms in particular expressed disappointment at failing to establish profitable offices in the region. These failures were all the more conspicuous as American firms’ decreasing dependence on intermediary distributors in London and elsewhere boosted efficiency and profitability in other parts of the world.

American trade press articles and letters in distributor archives illustrate a weakening of optimism as the basic situation failed to change through the 1910s and 1920s. In an article in Motography in 1912, the consul general in Beirut optimistically tried to tip off American companies to a potential market. He suggested that American firms route their films for the region through Cairo and Alexandria and claimed there was “no reason why a large business [could not] be immediately developed.”1 The relatively meager communication with Middle East and North African contacts in the Selig Polyscope collection of letters from the London office in the 1910s suggest some interest in potential markets in Cairo, Tunis, and Istanbul, but not necessarily a realization of that potential.2 In the following several years, trade articles about the region reported similarly frustrating film import situations but attributed the continuing inaccessibility to larger cultural obstacles such as the Islamic ban on images or the difficulty of setting up gender-divided screening spaces. Locations with better film distribution, such as Cairo or settler communities throughout the region, were cited as the exceptions that proved the rule.3 As one journalist emphasized, “Arabia, therefore, promises to be a difficult market, with the exception of the British administered Aden Protectorate, and the rather liberal Sultan of Mokalla.”4

As the trade articles expressed hope for future business, they also frequently noted the age and poor condition of the prints. The films shown in Aden, for instance, were described as “an exceedingly common or archaic type” and “weekly exhibitions of pictures several years old.”5 An article regaling readers with descriptions of the high-fashion picture palaces in Egypt ends with a discussion of other, more rural and far from opulent, theatrical sites: “When the films have been the round of the various picture palaces . . . they are bought up cheap by enterprising Greeks [who] make quite a thriving business out of dilapidated old films” by exhibiting them in the villages.6 The US consulate reported that theaters in Beirut, Damascus, and Tripoli were supplied by films that “would reach there only after having been used in a number of other towns and were often in bad condition and out of date.”7 These accounts of the troubled and interrupted circulation of worn and incomplete prints depict the diverse kinds of exhibition and reception of a considerable portion of the films screened throughout the region. These films were junk prints, forgotten by producers and amortized long before their arrival. Their life, a kind of afterlife, invites analysis as such.

As a term of admiration, not dismissal, junk prints organizes a rich set of associations. The term emerges in tandem with the growing circulation of goods in industrial modernity. It evokes a range of productive secondhand cultures dependent upon obsolescence, like the modern junk shop, but its associations with reuse date back much further. In the seventeenth century, junk described the reusable scrap line on sailing ships. This early definition might seem fitting for anyone who has worked with film fragments in an archive, in a projection booth, or on an optical printer. Someone with a reverent (and admittedly fetishistic) attitude toward junk film would likely notice how the practice of saving and mending frayed marine line does recall the modern labor of mending, saving, splicing, and threading old celluloid.

To refer to film as a kind of junk is nothing new. Importantly, the term described the circulation of secondhand prints in the silent era, and this usage noticeably features as the first modern example in the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of junk. The OED entry cites Valentia Steer’s 1913 study The Romance of Cinema, where the term is placed in quotes to note industry jargon: “The life of a film is very short. It is ‘first run’ today and ‘junk’ a few short weeks hence. What is now 4d. a foot, to be handled like a newborn babe, will, three months later on, be so much scrap, fit only for working up into varnish. Yet millions of feet of this worn-out rubbish are being reeled off daily at fourth[-] and fifth-rate picture theatres.”8 By The Romance of Cinema’s own coincidences of circulation, secondhand film has helped to define modern junk. Steer’s revulsion for “worn-out rubbish” notwithstanding, this coincidence indicates the importance of junk as a historiographical imperative in film and media studies.

Like garbage and trash, junk is associated with waste, an annoying by-product, a slur upon the otherwise pristine efficiency associated with modern industrialism. Junk’s visibility offends because it is nonsynchronous material.9 It refers at once to matter out of date, out of place, and to matter that piles up over time.10 A positive conception of junkspace can radically interrupt one-dimensional conceptions of media history, which, despite our best efforts, too often lean toward narratives of development and progress that overlook out-of-place historical material. These one-dimensional conceptions become even more dubious when tracing the histories of film’s global circulation, as they tend to assume a kind of simple delay from one place to another. The notion of a simply delayed film culture (as opposed to an incongruous one) comes too close to the touristic fantasy that one (peripheral) place represents the past of another (central) place.11 Junk, when foregrounded, confronts these assumptions, as junkspaces combine fragments of different historical periods in unplanned ways.

Junk augments the conceptions of archaeology that have influenced much of the post-1960s media historiography. Archaeology has proven an especially fruitful metaphor in film study, from classic work by C. W. Ceram to the authoritative recent history by Laurent Mannoni to experimental work by filmmakers such as Gustav Deutsch.12 Archaeology and junk are intimately related, whether acknowledged or not.13 A modern archaeology acknowledges the redundancy of a phrase like archaeology of junk. It aligns itself not with what the Futurists condemned as “the chronic necrophilia” of the archaeologists who fetishize antiquity but rather with the “perfume of garbage,” to the modernist interest in the material culture of the everyday and its surprising revelations.14 A modern everyday medium, periodically relegated to and rescued from junk heaps, with its own sour perfumes of decay, cinema proves an easier fit for this approach than most other media.15

To consider junk film’s afterlife makes clear that the life of a film, while still painfully short to the preservationist, turns out to be nowhere near as short as Valentia Steer assumed. From a transnational perspective, Steer’s “fifth-rate picture theaters” only begin the stories of the films’ afterlives. The description of film as “worn-out rubbish” could be taken now as a testimony to the longevity and adaptability of these prints. It could draw attention to how the films’ object-lives help to shape the translations that occur in new exhibition contexts. Case studies of the prints’ age and the intermediary stages of their circulation in the region reveal inventive and often counterintuitive reuses of junk film. The labors of reuse created value by reordering film reels and transforming their themes.

FILM TRAFFIC AND REGIONAL INFLUENCE

In following silent cinema’s steps toward sustainable commercial exhibition in Iran, the locations of regional relay points reveal as much as the places where the films were produced. Such relay points can often hide in plain sight. International commerce statistics provide some of the most accessible clues about the films shown on commercial screens in Tehran. There were around thirty cinemas operating in Iran in the late 1920s, with just under half of these located in the capital.16 These cinemas subsisted on a steady stream of imports accounted for in one report by the US Department of Commerce. Statistics confirm that American and French productions far exceed those of any other country, and their share of the market remains fairly stable despite taking an obvious hit from the economic crisis. The low numbers overall and the decreased numbers in 1930 mark disappointment in what the commerce department hoped would be “a promising field for exploitation.”17 But the origins and number of these imported films do not tell the whole story.

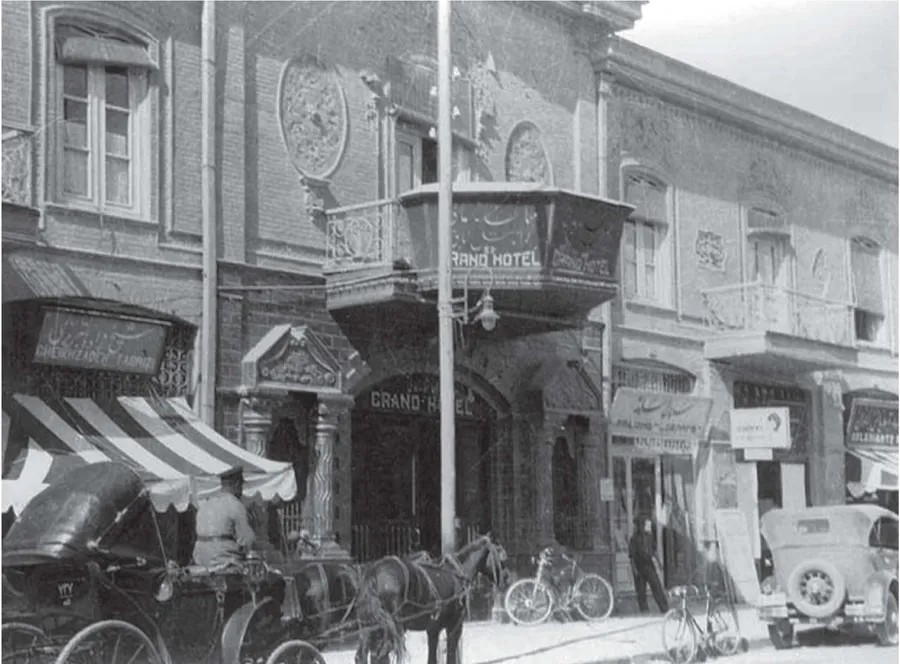

Exhibitor advertisements from the 1920s and 1930s in the Persian-language daily Ettela’at provide more information about the films represented by the import figures. Launched in 1926, the paper is one of the best sources for evidence about the films from this period. Cinemas advertised in Ettela’at from the beginning. In the first few years of the paper’s run, the only regular film advertisements came from the Grand Cinema operated by Ali Vakili in conjunction with the Grand Hotel on Lalezar Avenue (figure 5). Beginning around 1929, the film ads become more diverse, with cinemas Sepah, Zartoshtian (both also owned by Vakili), Pars, Tehran, and Baharestan among the frequent advertisers. These cinemas do not present a comprehensive view of film exhibition in Tehran, but the regularity of advertisements and continual experiments with tie-in stunts offer a glimpse into exhibition practices and policies at an array of major theaters in the city.

FIGURE 5. Outside the Grand Hotel, Lalezar Avenue, Tehran. Private collection.

Ettela’at ads indicate that the basic numbers provided in the Commerce Reports article are interesting for what they conceal as much as for what they reveal. The films I have been able to identify were typically eight to ten years old, and they were mostly serials. The gap between the original release date and local screening date common throughout the region is substantial in this case. Notable also is the silent serials’ prolonged popularity, which extended well into the early sound period. Some lag in exhibition chronology can be expected in any secondary market (including small towns in North America), but here the lag is particularly dramatic even compared with markets in China or major port cities in Latin America, where established exchange offices ensured rapid distribution. To say that the emergence of cinema was simply postponed in Tehran would neglect the most noteworthy aspects of this lag time: how elements of early cinema culture overlapped with 1920s modernism, how intermediary film exchanges exerted their own influence, and how mile markers of exhibition that were experienced elsewhere as continual sequence (the very premise of serialized stories) were often experienced in Tehran as simultaneity.

A cursory glance at the Commerce Reports article might suggest that American film dominates the market, followed relatively closely by France and distantly by Germany and Russia. But the circuitous trade routes and geographical intermediaries for these junk prints form as important a part of their story as their places of origin. Films and film culture routed through Istanbul or British-administered Baghdad seem to easily fit official culture in an Iran governed by a leader who would borrow many of his ideas about nationalist modernization from Atatürk and whose power was enabled by the British government. Intermediaries such as Moscow, on the other hand, created more complicated situations in the late 1920s.18 The film exhibition scene in Iran during the constitutional r...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Note on Transliteration and Titles

- Introduction

- 1. An Afterlife for Junk Prints

- 2. Circulation Worries

- 3. Collage Sound as Industrial Practice

- 4. The Anxious Exuberance of Tehran Noir

- 5. Eastern Boys and Failed Heroes

- Coda

- Notes

- Index