eBook - ePub

Iron Hulls, Iron Hearts

Mussolini's Elite Armoured Divisions in North Africa

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The campaign in North Africa during World War Two was one of the most important of the conflict. The allies fought for control of North Africa against the German Afrika Korps led by Rommel. But the part played by Mussolini's Italian troops, and in particular the armoured divisions, in support of the Germans is not so well known. This painstakingly researched book looks in detail at the role of Mussolini's three armoured divisions - Ariete, Littorio and Centauro - and the invaluable part they played in Rommel's offensive between 1941 and 1943. Indeed, the author is able to show that on many occasions the presence and performance of the Italian armoured divisions was crucial to the success of the axis campaign.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Iron Hulls, Iron Hearts by Ian W Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Segunda Guerra Mundial. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Mussolini’s War

Why were the Italians fighting with Nazi Germany against the British during World War II? Why did the deserts of North Africa become the main arena in which this struggle was played out? Why were the Italians almost entirely unprepared for this conflict? This chapter will attempt to answer these questions, and briefly outline how Italy became involved in a protracted war with Britain before it was ready.

It is probably no coincidence that the states that generated much of the international unrest in the period between 1860 and 1945 were Germany, Italy and Japan. They were new states of the 1860s; Germany and Italy had been formed by the unification of smaller states, and Japan had emerged from centuries of self-imposed isolation. This triad had to find their place in the hierarchy of the established powers: France, Britain, Russia, China and the United States. These had already secured their colonies, their spheres of influence and their economic zones; the new states had none of these things, but they wanted them. They were, naturally, opposed by the established powers, and the result was economic competition, international tension, colonial disputes and, ultimately, open conflict. Germany fought France in 1870, and France, Britain, Russia and the United States in 1914–18. Japan fought China in 1896, Russia in 1905 and Germany in 1914–18. Italy fought Ethiopia in 1896, Turkey in 1911 and Austria-Hungary and Germany in 1915–18. The outcome was a mixture of gains and losses, which left all the new states frustrated, unsatisfied, and still eager for change.

In 1918 Germany, defeated and forced to surrender territory and colonies, was clearly unsatisfied, and almost from the moment of defeat was planning revenge. In contrast, Italy and Japan had been on the winning side, and should have had few complaints. In fact, the Japanese remained frustrated despite securing additional territory. The Western Powers prevented them imposing colonial status on northern China, and treated them as racial inferiors – for example, by restricting Japanese immigration. This inflamed Japanese animosity towards the Western Powers, and fuelled their ambitions in Asia.

How did Italy fare in World War I? In 1914 the Italians had been allied with the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary. They had naturally gravitated towards Germany, another new state, with whom they shared a common interest in the revision of the status quo. They had been close allies during their respective unification struggles in the 1860s, when German assistance had proved instrumental in securing concessions from Austria-Hungary. This link was the primary reason for Italy’s alliance with the Central Powers, since Italy and Austria-Hungary were natural enemies with little in common. The latter was a polyglot dynastic relic of the Middle Ages, facing decline in an era of nation states. Italy coveted its territory in South Tyrol, Istria and Dalmatia. It was not a situation that provided the basis for a solid alliance, and when World War I erupted in 1914, Italy chose to remain neutral, partly through weakness but also because of her animosity towards Austria-Hungary. However, the bloody deadlock on the Western Front encouraged the rival combatants to tempt Italy into the war to shift the balance in their favour, and in May 1915 the Allied Powers, Britain and France, succeeded by promising, in a secret treaty, to satisfy Italy’s territorial ambitions against Austria-Hungary. As a result, the Italians endured more than three years of bloody fighting against the Central Powers, including a disastrous defeat at Caporetto, which almost forced them out of the war. They recovered with Allied assistance, and in November 1918 inflicted a crushing defeat on the Central Powers at Vittorio Veneto. In the end Italy suffered 650,000 dead, though she now anticipated receiving the rewards promised in 1915.

In the event, while Italy did secure certain territorial gains from Austria-Hungary, these were significantly less than promised by the Allies in 1915. She secured South Tyrol, Istria and Zara on the Dalmatian coast, but was denied Fiume and the rest of Dalmatia. The Italian nationalist poet, Gabriele D’Annunzio, described this as a ‘mutilated victory’, and it caused a great deal of resentment against the Allies, particularly amongst Italian nationalists. In September 1919, D’Annunzio staged a popular paramilitary occupation of Fiume, which the Italian government was unwilling to challenge, and Fiume was quietly absorbed into Italy. It was the first sign that Italian nationalists were not content with the post-war settlement, and were prepared to take direct action to change it.

Another source of Italian nationalist resentment, consequent on Italy’s late appearance on the international scene, was the lack of African colonies. In the 1880s Italy had secured a couple of worthless stretches of desert in East Africa, Eritrea and Italian Somaliland, the scraps left by the other European powers. An Italian military expedition was sent to expand this foothold by conquering the independent kingdom of Ethiopia. In 1896 it met with disaster at Adowa, when 10,000 Italians were massacred by a much larger force of Ethiopians; as a result Italian designs on Ethiopia were effectively shelved. In 1911, Italy seized control of Libya in North Africa from Turkey, but this area, too, was largely desert. The lack of rich colonies and the humiliation of defeat by Ethiopia rankled with many Italians, who were denied the economic and political benefits that usually accrued from the ownership of colonies.

In 1919, therefore, Italy was a nation whose ambitions remained unsatisfied. This was the background to the rumbling discontent of the inter-war years, and to Italy’s involvement in World War II. It did not, however, make an Italian alliance with the other discontented powers, Germany and Japan, inevitable; it merely showed that this triad shared a common dissatisfaction with the status quo that might draw them together. This had not been the case during World War I when they fought on different sides. The alliance of Italy with Nazi Germany and Japan was the result of events during the inter-war period.

In the immediate post-war period the European economy was bankrupt, and fear of imminent Communist revolution stalked Europe. On 28 October 1922, the Italian establishment therefore handed power to Benito Mussolini and his Fascist Party, and left them to deal with Italy’s apparently insoluble economic and political problems. They were well organized and strongly anti-Communist, and could therefore be expected to oppose the threat of revolution. If they failed, they could easily be replaced. Unfortunately they had not placed Italy’s future in safe hands. Mussolini had a strong will and natural belligerence, combined with a somewhat erratic temperament, and he introduced a considerable degree of instability to the heart of government. He was supported by a Fascist Party that was strongly nationalist and militarist. It included many of those who were most anxious for Italy to secure her rightful place in the world, and who would not shrink from using force to achieve their aims. They transformed Italy into a state that sought to increase its power and influence through military force.

The new regime made great play of its dominance of every aspect of Italian life – but it did not achieve as much influence as, for example, would later be secured by the Nazis in Germany. The Italian king, Vittorio Emanuele III, remained head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces, which also remained largely independent; thus as prime minister, Mussolini could declare war and provide overall political direction for the armed forces, but he could not command the military in wartime. This restriction clearly rankled, and in the 1930s, Mussolini personally assumed control of all three individual service ministries with the intention of influencing detailed military planning. This actually caused more problems, since no single individual could possibly fill so many roles adequately, and especially not a dilettante like Mussolini. (In contrast, Hitler made himself head of state in Germany, and the armed forces swore allegiance to him personally.) This meant that Mussolini’s power was not solidly based, and he was less able to impose his will on the military. As a result, in July 1943 the king was able to exploit his position as commander-in-chief of an independent military in order to depose Mussolini.

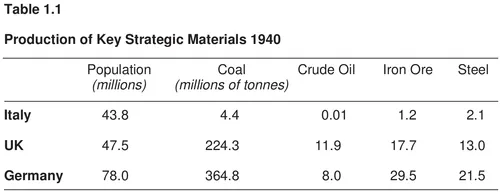

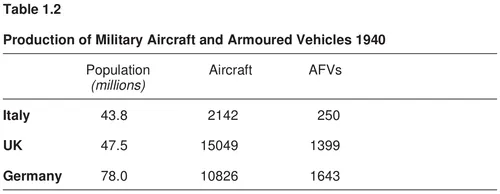

In the 1920s, Italy was a restless nation led by a belligerent demagogue supported by nationalists anxious to change the status quo. It was only the strength of the victorious allies, Britain and France, and Italy’s own weakness, which prevented any overt aggression during that decade. In fact, Italian economic weakness would always restrict Fascist ambitions. In the 1930s, Italy was a nation of forty-four million, not far short of Britain’s forty-eight million, but with a much smaller industrial base in comparison. An indication of this disparity can be gained by comparing production data for Italy, Britain and Germany: Table 1.1 provides comparative figures for production of some key strategic materials, and Table 1.2 comparative figures for military production. The figures show that the Italians were short of many of the raw materials essential for military production, with no significant indigenous sources of iron ore, oil or rubber. The Italian colonies offered neither sources of raw materials nor significant markets for Italian agricultural produce or manufactures. They were a drain on resources, rather than a source of support for the economy. It is ironic that millions of tons of desperately needed oil lay undiscovered beneath the sands of Italy’s otherwise worthless Libyan colony! At the time the Italians had to meet most of their raw material needs through imports, and to expend a high proportion of their national income to purchase these; Table 2 provides details of the levels required of some key materials, and the shortfall in securing these.

These stark economic facts of life meant that Italy had to restrict its ambitions to those that could be fulfilled in a short period of time and without coming into conflict with a great power. Alternatively, if they wanted to be more ambitious they needed to secure the support of one or more powerful allies. In this period, however, potential allies opposed to the post-war settlements, principally Germany and the Soviet Union, were themselves too weak to be of any help. This was the context within which Fascist Italy had to pursue its ambitions for territory and influence. A firm grasp of Italy’s economic limitations should have resulted in a lowering of expectations, but it simply left the Italians more frustrated than ever. Thus in the unfavourable circumstances of the 1920s they were forced to shelve their more aggressive plans – but only until the situation improved.

In the 1930s the situation was completely transformed by the rise of Japan and Germany, who increasingly challenged the established order in pursuit of their own frustrated ambitions. In 1931 Japan occupied Manchuria in north-western China by military force. Britain and France responded with strong words of condemnation, but no retaliatory action. This demonstrated the potential of any power that was prepared to act ruthlessly and ignore diplomatic obstacles, to defy the status quo. However, it was not until 1933, when Adolf Hitler and his Fascist-inspired Nazi Party came to power in Germany and determined to overthrow the post-war settlement, that those Italians seeking to overturn the status quo finally had a potential ally. But in spite of superficial similarities, the fundamental nationalism of the two fascist regimes presented a serious obstacle to any prospective alliance. Thus, the Italians considered German nationalism to be a potential threat to the territories seized from Austria-Hungary, as these contained German-speaking minorities; and the Germans were concerned about Italian influence in Austria, which they themselves wanted to absorb. This tension made early relations difficult, and provided scope for mistrust and misunderstandings. In July 1934 Mussolini dispatched Italian troops to the Austrian frontier when it appeared that Hitler might exploit a Nazi coup in Vienna to occupy Austria. It was only gradually that the fascist regimes were drawn together by their shared interest in overturning the post-war settlement.

In March 1935, Hitler renounced the disarmament clauses of the Treaty of Versailles and revealed the reconstruction of German military power. The European powers, including Italy, met soon afterwards at Stresa to formally condemn Germany; but they took no practical action. This weak response was further undermined by the British, who were prepared to appease Germany to avoid another war: in June 1935 they signed the Anglo-German Naval Agreement, which declared British acceptance of German rearmament and effectively shattered the post-war consensus. They did so without consulting the French or Italians, and so broke the Stresa Agreement before the ink was dry. The instability created by these events presaged the effective abandonment of the post-war system; it also encouraged the Italians to resurrect their own expansionist ambitions, and their covetous gaze quickly fell on Ethiopia.

A great deal of Italian frustration centred on Ethiopia, an undeveloped area blighted by slave trading and other barbarous customs, which the Italians considered it their right and duty to colonize. They were willing to offer the Ethiopians the same benefits that European colonization had brought to the rest of Africa. The British and French declared they had no designs on this area, although – frustratingly for the Italians – they sought to prevent the Italians from occupying it. The Italians could not understand the British public enthusiasm for an independent Ethiopia, which appeared hypocritical in the face of their own colonization of most of the globe. In 1934 a minor dispute on the borders of Italian Somaliland and Ethiopia caused them to resurrect plans for military conquest. The existence of a powerful revisionist Germany meant that Britain and France could no longer simply block Italian plans: they had to be circumspect about opposing Italy for fear of driving her into alliance with Germany. On 30 October 1935, therefore, an Italian army 100,000 strong was launched against Ethiopia on the basis of intelligence that Britain and France would not intervene militarily.

In the campaign that followed the Italians exploited their technological superiority to crush the large but poorly equipped Ethiopian forces: they used aircraft, tanks, artillery, machine guns, flame-throwers, bombs and mustard gas against poorly armed, badly trained and often barefoot tribesmen. The unforeseen possibility of military intervention by Britain made the Italians anxious to complete their conquest quickly – maybe this contributed to their ruthlessness, although it cannot excuse it. The Italians were condemned for this both at the time, and since, although they were behaving much like other European colonial powers before them. On 5 May 1936, the conquest was completed with the occupation of Addis Ababa, and the Italians finally had their empire. It had cost the lives of 2,766 Italians and 1,593 colonial troops on one side, and an estimated 50,000 Ethiopians on the other.

The Italian empire would also have other costs. The first was the economic cost of an Ethiopia that had not been fully pacified and was urgently in need of development. It consisted of a mosaic of different tribes, most of them hostile to each other and to any central authority, and the Italians had to install and maintain a large garrison of colonial troops from Eritrea. In addition they were obliged to improve the infrastructure of the country, initially by constructing the first network of metalled roads. As a result, Italian colonial expenditure rose from under 1 billion lire in 1934 to more than 6 billion in 1938. It was an expense that Italy could ill afford, and its new empire promised to be little more than a drain on resources, at least in the short term.

The wider political consequences of this Italian aggression were also important. In contrast to their appeasement of Germany, the British took a tough line towards Italy, introducing economic sanctions and mobilizing their Mediterranean fleet. This unexpected reaction briefly caused the Italians some anxiety, until they realized that the British could not risk open war in the face of the German threat. It is worth reflecting that if the British had allowed the Italians to occupy Ethiopia without demur, they might have secured a potential ally against Germany. And if, on the other hand, they had taken an even tougher line and imposed oil sanctions or closed the Suez Canal, they might have ended Italian ambitions there and then, and provided Hitler pause for thought. Instead, the British managed to antagonize Mussolini and unite the majority of Italians behind him without affecting military operations in Ethiopia. In addition, in March 1936 Hitler exploited the preoccupation with Ethiopia to reoccupy the demilitarized Rhineland: this was another blow to the post-war settlement. Furthermore, the British hostility towards the Italian occupation of Ethiopia pushed Italy towards Germany.

A common interest in overturning the status quo was beginning to draw Germany and Italy together. In July 1936 Mussolini and Hitler decided independently to exploit the outbreak of a right-wing military revolt in Spain to undermine the left-wing government. They provided increasing levels of assistance to the Nationalist rebels, including large amounts of military equipment and trained ‘volunteers’. In response, Soviet Russia supported the left-wing Republican government with her own military advisers and supplies. The fascist dictators had a common interest in ensuring that the Nationalists under General Franco were not defeated, especially following Soviet intervention. The Italians invested more than the Germans in a Nationalist victory in the hope of securing a counter-weight to France in the western Mediterranean. This participation in a common venture almost inevitably drew the fascist powers closer together. The Italian and German forces sent to fight in Spain worked together and developed close, if not always amicable, relations.

In spite of – or perhaps because of – the scale of foreign intervention, the Spanish Civil War was protracted and only ended in April 1939. The Italians eventually succeeded in securing a friendly regime in the western Mediterranean, but at immense cost. They sent 78,500 men to Spain and suffered 3,819 dead and 12,000 wounded. They also lost a significant amount of military equipment, since everything sent to Spain was left behind: this included 3,400 machine guns, 1,400 mortars, 1,800 artillery pieces, 6,800 vehicles, 160 tanks and 760 aircraft, and it represented a loss to Italy’s war inventory, although most of it was obsolescent. The financial cost of this war was probably more debilitating, amounting to between 6 and 8.5 billion lire, an immense drain at 14 to 20 per cent of annual expenditure. The heavy cost of this war severely handicapped Italy in the period leading up to the outbreak of World War II.

In the meantime, in Novem...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1: Mussolini’s War

- 2: The Birth of the Armoured Divisions

- 3: Baptism of Fire

- 4: Trial by Combat

- Plates

- 5: The Cauldron of Battle

- 6: The Mirage of the Nile

- 7: Iron Coffins

- 8: Last Stand and Retrospective

- Appendix I: Italian Armoured Divisions: Orders of Battle 1941–42

- Appendix II: Comparative Performance of Tank Weaponry 1941–42

- Bibliography

- Index