CHAPTER ONE

GENESIS – The Why and How of the First Land Rovers

At the turn of the twenty-first century Land Rover advertising boasted that a Land Rover was the only motor vehicle more than half the world’s population had ever seen. This was no exaggeration: the Land Rover had indeed been a massive worldwide success, and remains so. To paraphrase another slogan from a different kind of advertising, it had got to the parts other vehicles cannot reach – and other hugely successful products from the same stable had followed it. First came the Range Rover, then the Discovery, next the Freelander and most recently the Range Rover Sport. But all of this is very far from what the Rover Company’s technical chief, Maurice Wilks, had in mind when he drew his plans for the very first Land Rover with his fingertips in the sand at Red Wharf Bay, some time around Easter 1947.

To understand what was going on then, we have to look at the situation Rover found itself in during the first quarter of 1947. Like other British car manufacturers, Rover had suspended car manufacture during the Second World War and had devoted its efforts to building machines needed for the war – in Rover’s case, mainly aircraft components. Unlike some other companies, though, Rover found itself without a new car ready to put into production when hostilities came to an end in 1945. It hastily updated some of the cars it had last built in 1940 and started turning them out of the gates of its new factory at Solihull in the West Midlands.

While these cars had certainly been among those most admired by the professional classes in Britain at the end of the 1930s, they were by now old designs. Both mechanical technology and styling had moved on, and it was clear that Rover needed to move on, too.

But there was an even more urgent reason for developing new products. Shortly after the end of the war, the British government had announced that the country’s manufacturers must give priority to overseas orders. The idea, sensible enough in the circumstances, was that selling manufactured goods abroad would bring money into a Britain that desperately needed money after nearly bankrupting itself during the war. Rover had never made any serious efforts to sell cars outside the UK before and, although the company set to with a will, it quickly discovered that outdated products developed for the peculiar needs of the British market were not strong sellers elsewhere.

The situation looked bleak – and it was made bleaker by the Ministry of Supply’s assertion that it would ration steel, which was in short supply as the country emerged from war, favouring those users who performed best in overseas trade. If Rover couldn’t build a car that would sell well overseas, it might find its supplies rationed to such an extent that it would no longer be able to continue making cars at all.

Of course, there were several new projects on the boil. Maurice Wilks and his older brother Spencer, Rover’s Chairman, had guessed that small and economical cars would be in demand during the difficult period that would inevitably follow the war. That had been the case after the First World War and there was no reason to think the same would not happen again. So Rover’s designers had been set to work to draw up a new car called the M-type. That M stood for ‘miniature’, and the car was really a heavily Roverized adaptation of the pre-war Italian Fiat 500. It would certainly have been quite a remarkable machine, but by the first quarter of 1947 it had become apparent that small and economical cars were not what the world wanted as it struggled to get back to normality.

Work was going on to replace the revived pre-war Rovers, too. Maurice Wilks struggled at first to create something that might fit the bill, but was then hugely impressed by the Raymond Loewy-designed 1946 Studebaker Champion, and instructed his designers to borrow ideas from it, settling for a stop-gap model while the new car came together. The stop-gap, which looked much like the pre-war Rovers but had more modern running-gear, arrived in February 1948. Like the cars it replaced, however, the P3 model was never going to set the world on fire. Rover still needed a product that would have appeal in overseas markets, and by the end of 1946 – a year after the war’s end – the problem was a pressing one.

That winter proved to be one of the hardest on record in Britain, and snow and ice made it difficult to use the long drive at Maurice Wilks’ home of Blackdown Manor near Leamington Spa. Wilks borrowed a wartime Jeep from his near neighbour, Colonel Nash, to use between house and road. March then brought severe gales, which brought down trees across the drive. So Wilks visited the local military surplus dump and bought himself a Lloyd Infantry Carrier, a small tracked vehicle that wasn’t daunted by mud or snow and had the power to haul the fallen trees out of the way.

Meanwhile, the borrowed Jeep had left a deep impression. Wilks liked it so much that some time around late May or early June 1947, he took it over in a swap involving his tracked carrier. But it had already inspired him to toy with the idea of Rover building a similar vehicle, using existing production components. The Rover version wouldn’t be primarily for military use, of course, but would be aimed at farmers and others who worked on the land, and would suit light industrial uses as well. Willys had in fact turned their wartime military model into just such a maid-of-all-work over in the USA, and Wilks was more than likely aware of the fact. A utility vehicle like that might be exactly what Rover needed to earn overseas sales and keep themselves going until better times returned.

Over the Easter of 1947 (Easter Day that year fell on 6 April), Maurice Wilks and family were on Anglesey, where they had recently bought a holiday cottage. Spencer Wilks already kept his boat there, and brought it around to Red Wharf Bay to visit his brother. Witnesses remember Spencer rowing ashore and the two men sitting down together as Maurice explained how a Rover 4×4 might be laid out, drawing his ideas in the sand. By the time that Easter holiday was over, the two brothers were sure they were onto a winner. When he returned to Solihull, Maurice instructed five Section Leaders in the Rover Drawing Office to get on with turning his idea into reality.

Designing the Land Rover

The Rover Drawing Office was the company’s engineering design section, all drawing boards and sliding rulers in those days. It was divided into sections dealing with the different major elements of car design, and it was five leaders of those sections who received Maurice Wilks’s brief for the new vehicle: their names were Gordon Bashford, Joe Drinkwater, Tom Barton, Frank Shaw and Sam Ostler.

Gordon Bashford’s job was to design the new chassis frame, and he remembered many years later that one of his first tasks was to visit a military surplus dump somewhere in the Cotswolds and to buy four Jeeps so that the Rover design team could take them apart and discover what made them tick. Bashford decided to use box-section side members rather than the Jeep’s channel-section members, which were notoriously prone to cracking. The box section would give vital extra strength, and Rover was already wedded to the idea of using the same principle for its forthcoming 1948 cars.

Work on the engine fell to Joe Drinkwater. He had to adapt Rover’s brand-new 4-cylinder engine, largely designed before the war by Chief Engine Designer Jack Swaine, to suit its new role in the proposed utility 4×4. In charge of transmissions was Tom Barton, a no-nonsense ex-railway engineer, and it was his job to draw up a two-speed transfer gearbox to bolt onto the existing Rover car gearbox and give the new vehicle crawler ratios for driving across rough terrain. On this he worked closely with Frank Shaw, head of the Transmissions team, who was also assigned to the 4×4 project. The fifth designer on Maurice Wilks’s new team was Sam Ostler, whose job was to come up with the bodywork for the new vehicle.

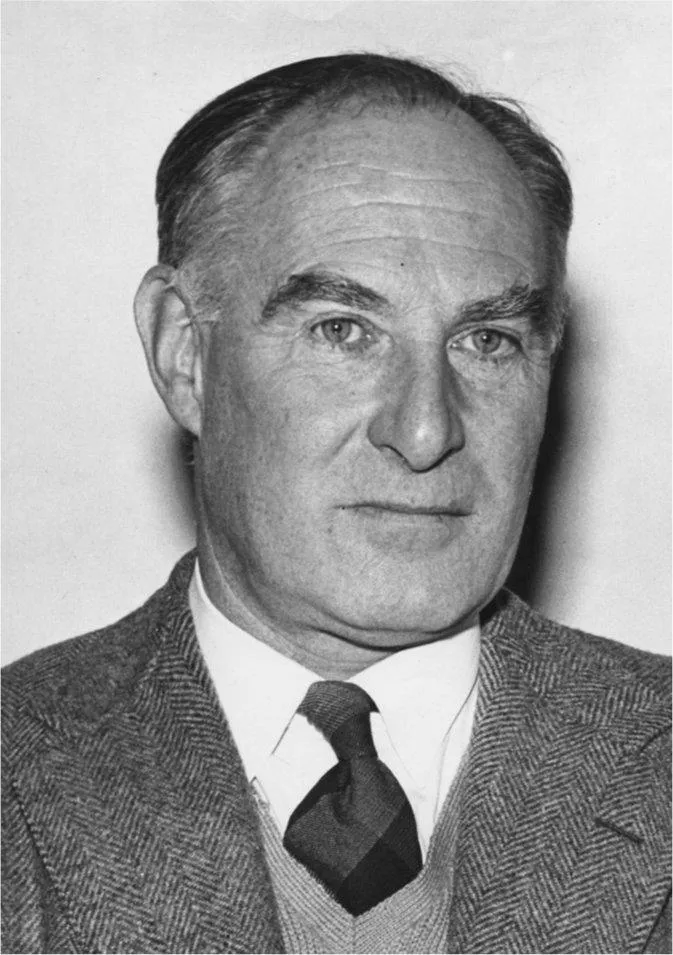

Maurice Wilks

Maurice Wilks was a gifted engineer who was very highly regarded in the British motor industry. Those who knew him remember a man of boyish enthusiasms, and yet he was also ‘a quiet, shy, studious man … [who] … shunned publicity and preferred to remain in the background’, as the Rover News company newspaper observed on his death.

He was constantly coming up with new inventions, both within and outside the automotive field, and patented many of them. His nephew Spen King, who also became a hugely important figure in the history of the Rover Company, described him as an ‘instinctive’ engineer, and this perhaps explains why Maurice Wilks had so little regard for keeping records. He liked nothing better than to try an idea out in the metal; it could be turned into a formal engineering drawing afterwards if it worked.

Maurice Fernand Cary Wilks, born in 1904, was one of three brothers. Educated at Malvern College, he gained his initial experience of the motor industry with General Motors in the USA, where he worked between 1926 and 1928. On his return to Britain, he became a planning engineer with the Hillman Motor Car Company in Coventry. His older brother Spencer was already there as Joint Managing Director with John Black, who would later become the authoritarian driving force behind Standard-Triumph.

In 1928, however, the Hillman company was bought out by the Rootes brothers, whose reorganization of the company prompted many staff to leave. Several key people found their way to Rover, including Spencer Wilks, who was appointed as the company’s General Manager in September 1929 and became Managing Director four years later. Maurice Wilks joined him shortly afterwards on the engineering side of the company; he was then twenty-five years old.

Maurice initially went to work on the Scarab, a rear-engined light car that was very much part of the old Rover management team’s thinking. However, as the Depression had its effect on the motor industry, it became clear that the Scarab was not the way forward, and the project was abandoned.

At this stage Rover’s business position was unstable. It was trying to compete in several different sectors of the market, and as a result was making a wide variety of very different cars. Spencer Wilks believed this was a mistake, and together with his brother, who had become Rover’s Chief Engineer in 1931, set about planning a rationalized range of cars, sharing common components wherever possible. These cars were carefully designed to suit Britain’s professional classes, a segment of the market that the Wilks brothers understood very well. Their introduction in 1934 was the beginning of a complete turnaround in the Rover Company’s fortunes.

Spen King remembered that Maurice Wilks’s enthusiasms in the 1930s also embraced flying. As a boy, King was taken for a hugely memorable spin in Uncle Maurice’s light plane.

In...