![]()

Part 1:

The Facts

![]()

Chapter 1

Principles of Flight

An aircraft flying straight and level is influenced by four forces, as shown in Fig. 1.1, and is in balanced flight when they are in equilibrium, i.e. when lift equals weight and thrust equals drag.

1. | Lift is the upward force created by the wings and is assumed to act through a central point known as the centre of pressure. |

2. | Weight of an aircraft is expressed in either kilograms or pounds and is assumed to act through a central point known as the centre of gravity. |

3. | Thrust is the force of the engines, normally expressed in kilo Newtons or pounds, which propels the aircraft forward through the air and is assumed to act in line with drag. |

4. | Drag is the result of the air resisting the motion of the aircraft. |

Fig. 1.1 The four forces acting on an aircraft.

Lift

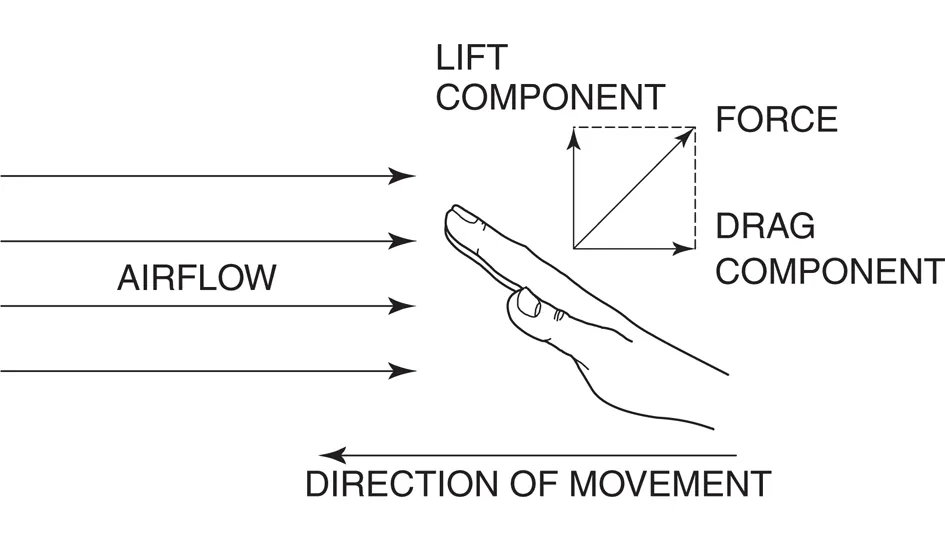

If a driver extends his hand out of a moving vehicle and holds his flat hand inclined to the airflow, the flow of air passing over the surface of the hand produces a force that lifts the hand upwards and pushes it backwards (Fig. 1.2). The upward component of the force is known as lift and the backward as drag. A wing is a more refined shape than a flat hand but produces lift in exactly the same way, although a lot more efficiently. An aircraft wing is fixed to the structure at an angle relative to the airflow as it flies through the sky. Air going the long way round, up and over the curve of the wing, is forced to increase speed resulting in an area of low pressure being induced on the top surface that draws the wing upwards. Some lift derives from the airflow striking the lower surface of the wing creating an increase in pressure forcing the wing upwards, but the greater lift results from the reduction in pressure above.

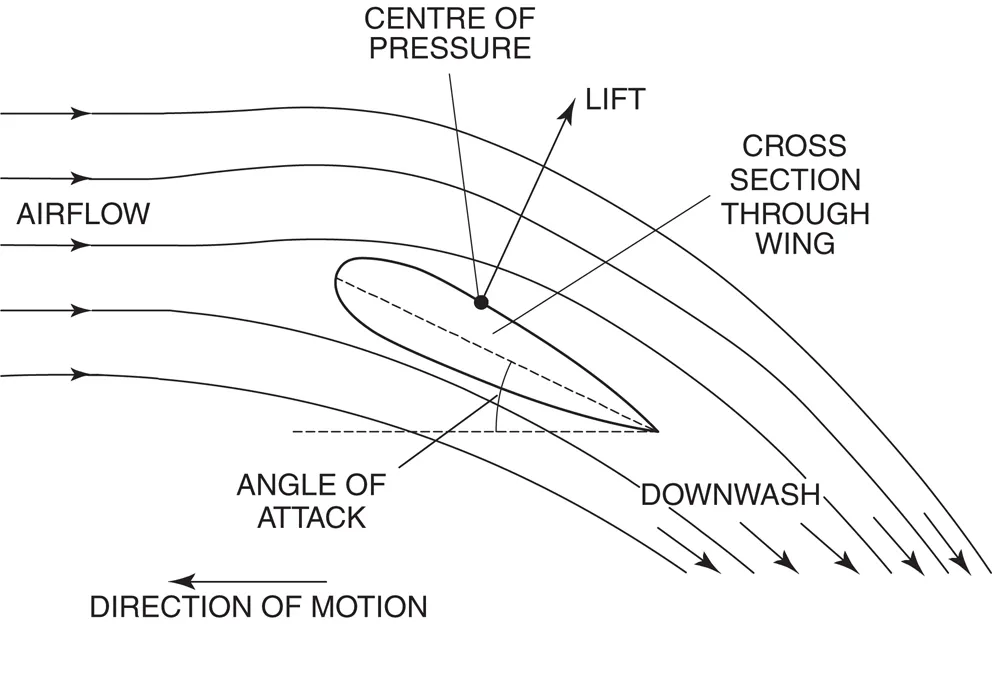

The area of low pressure on top of the wing is not a vacuum but simply a reduced value of pressure relative to the surrounding air, and is shown as negative pressure. The area of high pressure below the wing is, similarly, an increased value relative to the surrounding air and is shown as positive pressure. The pressure pattern distribution surrounding an aircraft (Fig. 1.3) clearly shows the greater effect of the negative pressure in the lifting process. To describe lift in more precise terms it can be said that the low and high pressure areas above and below the wing combine at the trailing edge as a downwash from which the wing experiences an upward and opposite reaction in the form of lift. Thinking of lift in simple terms, however, it is not so ridiculous as it seems to imagine the aircraft being sucked into the air by the reduced pressure above the wings.

Fig. 1.3 Pressure pattern distribution around an aircraft.

Lift is affected by a number of factors. The density of the air affects lift: the higher the density the greater the lift. The airspeed over the wing, i.e. the true airspeed (TAS) of the aircraft, affects lift: the faster the speed the greater the lift. The angle at which the wing is inclined to the airflow, known as the angle of attack (Fig. 1.4), affects lift: the larger the angle the greater the lift. Since the wings are firmly fixed to the structure, the angle of attack is varied by pitching the aircraft nose up or down and is referred to as the attitude of the aircraft. To maintain constant lift, therefore, as in level flight, variation in true airspeed requires adjustment of aircraft attitude; i.e. faster airspeeds require a lower nose attitude and slower airspeeds a higher nose attitude. Wing surface area is also a function of lift: the larger the area, the greater the lift. The bigger and heavier the aircraft, therefore, the larger the wingspan and wing surface area required to produce sufficient lift. Today’s large jets are constructed with wings of enormous size, the Boeing 777-300X having a wingspan of 64.9 metres (213 feet), the same as the Boeing 747-400 wingspan.

Fig. 1.4 Angle of attack.

On modern jets the wings are swept back at a large angle (the Boeing 777 at 32°) to allow aircraft to cruise at high speeds by delaying the onset of shock waves as the airflow over the wing approaches the speed of sound (see Chapter 6 - Flight Instruments). At slow aircraft speeds, however, the lift-producing qualities of the wing are poor. High-lift-producing devices in the form of leading and trailing edge flaps are required and, when extended, increase the wing surface area and the camber of the wing shape (Fig. 1.5). With flaps fully extended the wing area is increased by twenty per cent and lift by over eighty per cent. Flaps increase lift, allowing slower speeds, and also increase drag, which retards the aircraft. Canoe-shaped fairings below the wings shroud the tracks and drive mechanisms used in flap operation.

Leading edge flaps and slats extended.

To improve lift at take-off, flaps are set at five or fifteen degrees, depending on circumstances, any increase in drag being more than compensated by increase in lift. Take-off without flap is not possible at normal operating weights. On landing, thirty degree flap is selected in normal circumstances with twenty degree flap being reserved for abnormal system situations and contaminated runways.

Fig. 1.5 The effect of flaps on wing surface area and camber.

Large jets departing fully laden on long-haul flights require long takeoff runs in the order of 50–60 seconds duration before becoming airborne. At the required speed for take-off the pilot raises the aircraft nose (called rotation) to a predetermined pitch angle, to increase the angle of attack to the airflow with a resultant increase in lift, and the aircraft climbs into the air. At maximum take-off weights the big jets require speeds in the region of 165 knots (190 mph or 305 km/hr), and major airport runway lengths are normally about three and a half kilometres (over two miles) to accommodate the take-off distances required. Not all take-offs, of course, are at maximum weight, and at lower weights less lift is required. The aircraft lifts off at lower speeds and therefore requires a shorter run along the runway.

Weight

Although aircraft weights are normally given in kilograms or pounds, the enormous weight of today’s big jets becomes meaningless to many people when expressed in hundreds of thousands of a particular unit, and an appreciation of the weights involved is often better achieved by stating them in larger terms. One tonne (or metric ton) is equal to 1000 kg, which also equals 2200 lb. One ton is equal to 2240 lb. One tonne, therefore, is almost equivalent to one ton, being only 40 lb lighter. Whether units are stated in metric or imperial, or pronounced as tonnes or tons, can be seen to make little difference, and to simplify matters all weights are expressed in tons. Take, for example, the maximum take-off weight of the Boeing 777-200 of 297,600 kg or 656,000 lb. Stating this weight as almost 300 tons brings home to most the size of the aircraft. The maximum take-off weight of the 777-300X is 340 tons and the 747-400 is 397 tons.

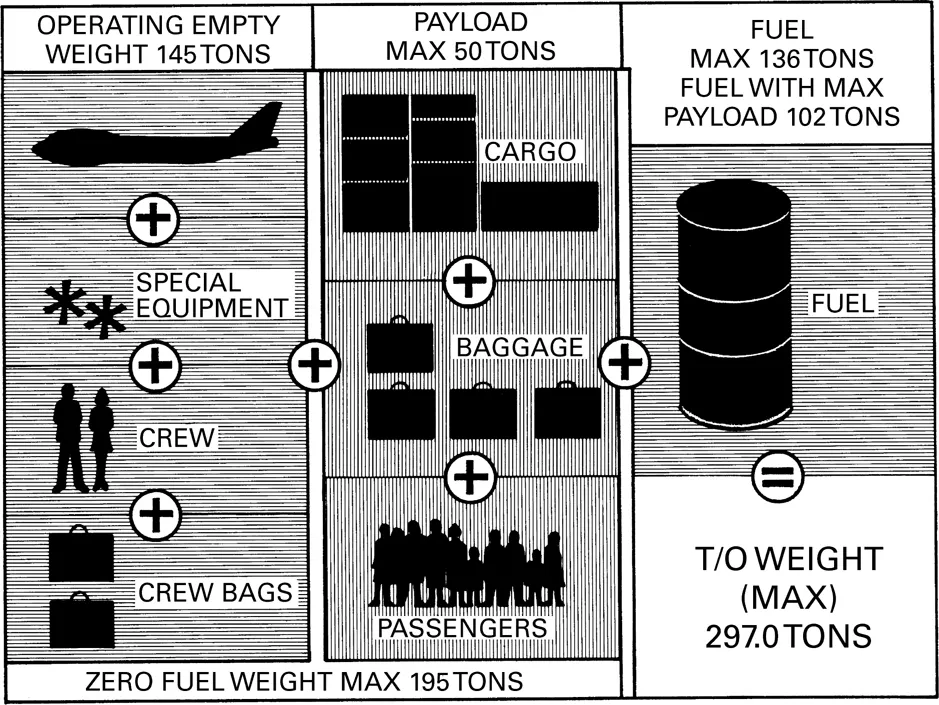

Fig. 1.6 Take-off weight – Boeing 777-200 Series.

United Airlines Boeing 777.

Aircraft loading

To the basic weight of an aircraft is added the weight of the equipment and the weight of the crew and their bags, the resultant figure being known simply as the operating empty weight. To this weight is added the payload, which consists of the weight of the passengers (males at 78 kg/170 lb, females at 68 kg/150 lb, children at 43 kg/95 lb and infants at 10 kg/22 lb – including hand luggage and necessities) and the weight of the cargo (including passenger baggage). The operating empty weight and the payload account for all weights excluding fuel and together are known as the zero fuel weight. To the zero fuel weight is added the weight of the fuel to obtain the final take-off weight (Fig. 1.6). The total aircraft weight at any point in the flight is known as the all-up weight (AUW).

The Boeing 777-200 series approximate operating empty weight is 144 tons. Since the maximum structural weight is 297.5 tons, the maximum weight of 153.5 tons of payload and fuel able to be carried is more than the 777-200’s own weight! The maximum fuel load depends on the specific gravity of the fuel and the maximum capacity of the fuel tanks and is about 137.5 tons. The maximum number of passengers depends on the maximum number of seats it is possible to fit. The 777-200 has a seating capacity of 300–375 and the stretched 777-300 a seating capacity of 370–450, depending on the seating configuration.

Average weights for a Boeing 777-200 on a seven-hour flight are: operating empty weight 144 tons; payload 30–40 tons; fuel 50–55 tons (of which about 45 tons is used, the rest in reserve), and take-off weight 220–240 tons.

Flap 30° set for landing.

Weight and balance

Weight distribution on an aircraft is very important: incorrect loading can result in the aircraft being too nose-heavy or too tail-heavy and beyond the ability of the controls to correct. Payload weights and distribution are, therefore, carefully pre-planned. Most cargo (including passenger baggage already weighed at check-in) is pre-loaded on pallets designed to fit the shape of the hold. The weight of each pallet is noted and its position carefully arranged. The pallets are raised...