- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Aerobatics

About this book

Acclaimed worldwide as the most detailed and knowledgeable text about Aerobatics, this book takes the pilot from the basic manoeuvres step by step through to the exacting standards required at World Championship level. Primarily for pilots, the book also makes light reading for enthusiasts and spectators.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 |

Why? |

For centuries, man watched with envy the flight of birds, and dreamed of being able to match their skill and grace. The unsteady, shaky flight of the earliest aircraft was a far cry from the effortless soaring of the birds, and far from being satisfied with their efforts, men still yearned for the same ease of control and manoeuvrability which persistently evaded their grasp.

Better aircraft with more reliable engines began to appear, and the pilots of these machines vied with one another at early flying demonstrations to prove the superiority of their craft. It was during such a meeting that the Frenchman Pegoud performed the first aerobatic manoeuvre when he looped his Bleriot. The First World War was responsible for a very rapid advance in the design of aircraft, and very soon it was found that the pilot with the more powerful and manoeuvrable aircraft would emerge victorious in air combat.

M. Adolphe Pegoud on his looping Bleriot Monoplane

At this time, pilots began to realise that the control, strength and power of the aeroplane could be made to conform to their will to produce an intricate pattern in the sky, giving them a sense of freedom that no man before them had ever enjoyed. They were flying with the ease of birds and the sport of aerobatics had been born.

Aerobatics soon became synonymous with stunt flying, unfortunately, and for many years was regarded as the wicked lady of aviation. Yet the lure of the pure aerial ballet remained and between the wars only a few timid pilots could resist the temptation to learn the art of aerobatics. At that time, the biplane reigned supreme, and unfortunate is the man who has not stopped to watch a tiny silver biplane high among the cumulus clouds, the sole performer on a stage of infinite breadth and indescribable grandeur. The roar of the engine is muted to a far-off drone, no louder than a bee in the summer sky, and the sun glints and sparkles on the wings and cowlings as the aircraft loops and rolls with easy grace.

How many thousands of unknown spectators are the audience to this performance? The pilot, oblivious to the envious watcher, sits behind a small windscreen, his hands and feet resting lightly on the controls. The air is crisp and clear and he is alone in the sky.

The sound is very different here, the muted drone is a deep-throated snarl that blends with the roar of the slipstream and the howl of the bracing wires. To the pilot this is no mere machine, but a living creature, quivering with life, eager to respond to every pressure on the controls. The slipstream thunders around the cockpit, tugging mischievously at the pilot’s leather helmet and goggles. The propellor is a whirling disc, shimmering in the sun, and the instruments, trembling, tell their own stories – airspeed, altitude, engine rpm, oil pressure and temperature, fuel contents, sideslip. The pilot scans these at a glance, not really studying any one of them, but knowing that all is as it should be.

A slight back pressure on the stick and the aircraft soars upward, stick and rudder smoothly co-ordinated, and the little biplane is poised on a wingtip, the slipstream dying to a sigh while the engine noise becomes harsh and strident. Now the nose is dropping and the slipstream rises to a shrieking crescendo, drowning even the engine’s blare. The controls become heavy as the airspeed indicator shows the speed rising towards the maximum. The pilot’s movements are quite small now, for the aircraft responds very quickly to the slightest pressure.

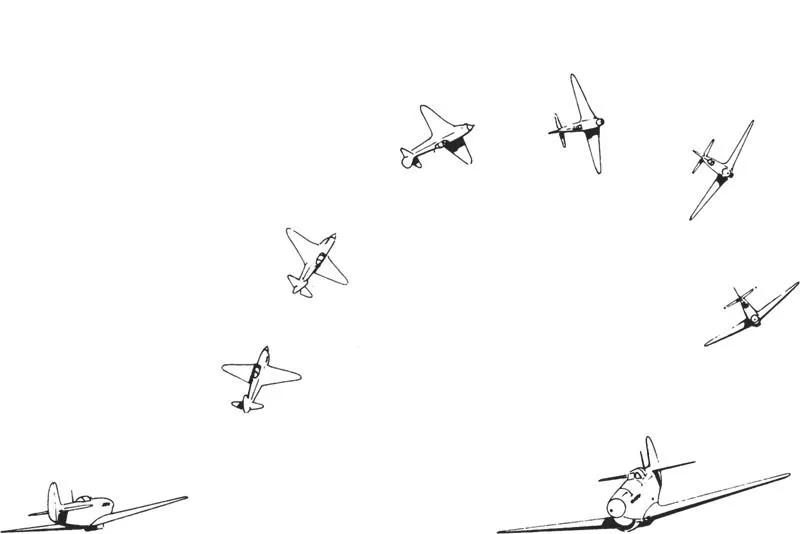

Slowly the nose comes up and as the aircraft comes out of the dive, the pilot presses back harder on the stick. The machine arcs upward, the flying wires tight with strain, while the landing wires, relaxed, vibrate until they are blurred. The “g” forces press him down into his seat and his muscles are tensed as he combats the rising acceleration. Now the climb is vertical and the pilot looks up and back for the horizon to appear. The pull force is easier now and as the top wing comes into line with the horizon, the pilot eases the stick forward. With hardly a pause, the stick is pressed to the right and the horizon revolves slowly. A touch of right rudder and the roll off the top is complete. Another wingover, this time soaring above the peak of a snow white towering cumulus cloud, before diving again for a lazy, flowing, slow roll, so beautifully controlled and easy that the watchers on the ground are unaware of the months of practice to achieve it.

Wing-Over

For most pilots, the sense of achievement and freedom is sufficient reward in itself – coupled with the knowledge that a pilot skilled in aerobatics is a much more accomplished pilot, since he knows the limits of his aeroplane and how to get the best out of it. The art of aerobatics brings confidence and increases skill, touch, and an understanding of the finer points of aerodynamics – in a way that cannot be accomplished in any lecture room.

It is inevitable in such an advanced form of expression that those who excel will become interested in competition, for this is one way of determining just how good a pilot really is.

Competition flying is not a relaxing business, though, and many good aerobatic pilots prefer the enjoyment of flying for their own recreation rather than undergoing the pressures of contest flying.

For those who do enter competitions, there is all the colour and drama that anyone could wish for. At international meetings, pilots from fifteen to twenty countries arrive at the contest airfield with brilliantly painted machines.

Then comes the most enjoyable part; the training period, during which each competitor is allowed two practice flights over the airfield. Pilots walk up and down the lines of aircraft, renewing old acquaintances and making new ones. Occasionally one finds an aeroplane with a diagram of its pilot’s aerobatic sequence attached to the panel and these are studied with interest. Some pilots with a strong sense of humour have been known to leave impossible sequences fixed to their aircraft and then to retire to a safe distance and watch the expression on their rivals’ faces.

The waiting is the worst, especially for the first round of the competition. Many pilots at this stage ignore their rivals’ performances and try to relax in their tents. Once in the aircraft, with the engine running, the initial nervousness disappears and one becomes impatient to get airborne. Preflight checks are usually carried out about three times each, because there must be no mistakes at this stage.

The starter’s flag drops and we start the stopwatch. All nervousness has disappeared as we open the throttle for take-off. The climb is initially straight ahead, as the pre-aerobatic checks are carried out (one never sees a pilot showing off at a world championship event).

The climb pattern has been planned to put us at the correct height directly over the start point, marked by a cross on the ground. During the climb, we check to see if our four datum points are clearly visible on each end of each axis and we monitor our engine instruments.

We rock the wings – the signal that we are about to begin – and roll the aircraft into a dive straight above the main axis. Now we are almost over the centre of the field and can no longer see the axes. We think of those competitors who have a vision panel in the floor and resolve to modify our own aircraft. But there is no time now to think of that, we have full power selected. We make small and instinctive corrections for turbulence and after a quick check of the airspeed, the stick comes back hard and the aircraft shudders as the needle on the accelerometer peaks on the red line. The pitch is checked sharply as the aircraft hits the vertical and full right aileron is applied. The wingtips race around the horizon, which is blurred because of the high rate of roll. The datum points flash past — one, two, three, four — and the roll is checked exactly on the last one. The vertical climb is held until the speed is no longer reading and the power is cut right back to idle. As the aircraft starts to slide backwards, the stick is eased back a little and rudder and stick are then held as firmly as possible. The controls are trying to snatch over, and we hang on grimly. Suddenly the nose goes down hard in a vicious hammer-head stall; as it does, we apply full power, and as the engine roars back to life, we hit hard rudder and forward stick for a vertical diving outside flickroll. We cut the power again and recover after one turn, checking that our flight path is exactly vertical. We also note that we are exactly over the intersection of the axes; perhaps we don’t need that clear vision panel after all!

So the sequence goes on for up to thirty manoeuvres of exacting precision flying, so different in concept from the antics of the little biplane high above the clouds, but equally as rewarding.

The combination of the two styles is probably the most exacting and difficult to achieve, and is the ultimate in aerial ballet. The effort is great, the concentration intense, the workload high, and the rewards infinite.

With each step, new vistas of knowledge and skill open up ahead; there is no place here for the man who professes to know it all. Here, with every freedom in space and time, man can satisfy his inner cravings, where science and art are blended into one, and where at last he can achieve mastery in the air.

2 | The raw material |

“If God had meant man to fly, he would have given us wings”. So preached Bishop Wright, father of Orville and Wilbur, before his sons achieved the success that was to change the face of the world.

Yet, in a sense, Bishop Wright was correct, because the air is not man’s natural element; he must always be an intruder. Pilots are made, not born. The “natural” pilot is really a myth, boosted by boy’s adventure stories, and later, by the T.V. and film industry. What is really meant is that those individuals who have good physical and mental co-ordination will learn more quickly; and the RAF’s accent on sport in the selection and training of pilots is indicative of this.

But there is no question of “supermen” here. Almost anyone can learn how to fly an aeroplane; indeed, at the time of writing, about 100,000 licences have been issued in this country. Why is it, then, that only a handful of pilots regularly fly advanced aerobatics.?

The primary fault lies in the bar or crewroom of the average flying club. It only requires a discussion to be started about stalling and spinning for the various “pundits” to go into nauseating detail about that horrific occasion when they were introduced to these exercises; and the detail will have lost nothing by repetition over the years. Student pilots will be alarmed by such stories, and a barrier will be raised in their minds which can effectively prohibit them from thinking and acting coherently when they eventually encounter that terror of the air, the spin.

I have trained pilots such as these, and others who have never been told that aerobatics are difficult, or dangerous, or make one feel unwell, and the second group learn much more quickly, and make better aerobatic pilots. I suppose it is impossible to suppress tales of fright and airsickness, because there seems to be some kind of morbid pleasure in the telling. It would appear to be “manly” to force oneself to overcome real fear, and to continue to try to keep up appearances, when in fact the last thing a student wants to do is to step into an aeroplane.

In the first place there is nothing wrong with being afraid of flying; lots of people who are extremely courageous in other spheres are not able to master their concern here. I am afraid of potholing — so I don’t do it. In the same way, if there is a genuine fear of flying, the best thing to do is to find some other occupation. It is all very well proving how brave you are by continuing, but this can only be to the detriment of your instructor and other pilots. A frightened pilot will never fly as accurately or safely as he would want to. In any case, flying is supposed to be fun, so why pay a lot of money to be frightened?

In some cases, a student may have been frightened by being exposed to aerobatics poorly performed, at an unsafe altitude; and this can leave an indelible mark on his future piloting career. This is a different kind of fear, and this can be overcome by patient explanation, and a gentle introduction into well flown aerobatics at a safe height.

Mention aerobatics and the first reaction will be the possibility of airsickness. I am often asked after an aerobatic display if my stomach is still in good working order — and this question has even been asked by Air Force personnel; so how can one expect the average student or private pilot to react differently? It is certain that with regard to airsickness the biggest problem lies in the mind. One can experience nausea without actually moving one’s body; the result of movement is the disorientation caused by the semi-circular canals in the ear. The physical result of these is the same and is directly traced to the brain, which also receives stimulus from the amount of pressure being exerted on the body, and the distribution of this pressure. For example, if one rides on a roller coaster at the seaside, when the car plunges down an incline, one’s “stomach is left behind.” But we know that the stomach does not move; so what causes the sensation? It is the result of change of pressure distribution from the seat to the floor, which transmits a message to the brain which says “I am falling”. If one is now strapped securely to that same seat, and if one’s feet are held clear of the floor, the sensation is no longer present. There is a jolt against the belt, and that is all. Now we have a parallel with a common problem in flying; either encountering turbulence or entering a dive suddenly. Merely tighten your seat belt and don’t jam your feet hard on the floor, and the sinking sensation will disappear.

This same sensation is often present in a poorly demonstrated stalling exercise and is one of the reasons for the dislike of the exercise. It can of course be greatly reduced by the use of the above technique, but it can be eliminated altogether by a little thought on the part of the instructor.

For some reason, when the stall is approached, the nose is raised to an incredible angle, and before the stall proper is reached, the instructor heaves back on the stick and the aircraft rears up, everything goes quiet, and then gravity really takes over as the misused aircraft carries out the inevitable “hammerhead” stall. Down goes the nose with a bang, and another frightened and disillusioned student joins the ranks of the straight and level brigade.

There is absolutely no reason why this technique should be adopted; it doesn’t teach the student what the accidental stall is really like, and if the aircraft won’t stall properly then he should be shown on an aircraft that will, instead of having the wits scared out of him. I have had the task on many occasions of coaxing students into being shown a real stall after just such an experience. Invariably their reaction was “is that all it is?” And then they try it themselves; no more fears, no more “queasiness”; and more important, now they are mor...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Why?

- 2 The raw material

- 3 Preparation

- 4 Pre-aerobatic training

- 5 The basic manoeuvres - the loop

- 6 The basic manoeuvres - the roll

- 7 The basic manoeuvres - the stall turn

- 8 Basic combination manoeuvres

- 9 Basic sequences

- 10 Inverted flying and turns

- 11 Acceleration

- 12 Limitations

- 13 Developing the roll

- 14 Developing the loop

- 15 Outside manoeuvres

- 16 Aresti explained

- 17 Fractions of flicks

- 18 The vertical roll

- 19 Advanced spinning and falling leaf

- 20 Wind and its effects

- 21 Advanced sequence construction

- 22 What is a lomcovak?

- 23 Tail slides and torque rolls

- 24 Knife flight and bridges

- 25 Aerobatics unlimited

- 26 Training methods

- 27 Low level aerobatics and display flying

- 28 American manoeuvres and terms

- 29 Aeroplanes for aerobatics

- 30 At the competition

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Aerobatics by Neil Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Aviation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.