![]()

Chapter 1

Flight Preparation

FLIGHT PLANNING

It is one-and-a-half hours before the 8pm departure of Skybird 787, a flight from Narita airport, Tokyo, to Los Angeles. Captain Yakota is in a taxi as it approaches the security checkpoint at Narita airport’s protected perimeter.

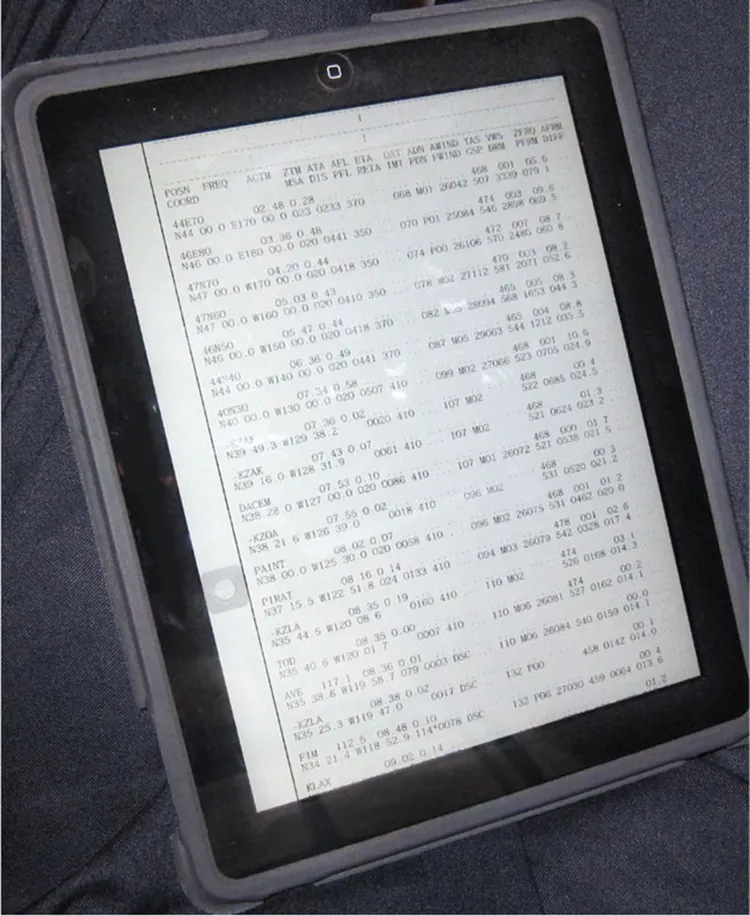

The security guard at the checkpoint inspects Captain Yakota’s security pass and waves the taxi through. Earlier the driver had picked up Captain Yakota at his home for the journey to the airport to command this evening’s flight to Los Angeles and, whilst travelling, the captain logs on to his company’s website on the Internet. He retrieves a copy of the flight briefing package for Skybird 787’s sector from Narita to Los Angeles and downloads it into his iPad for perusal.

The flight briefing package contains the Air Traffic Control (ATC) filed flight plan, the en route weather maps and other operational details such as expected passenger and cargo loads, planned fuel load and the airplane weights. He studies the weather reports for the departure and arrival airports and for the flight planned route. Good weather is reported for Narita, clear skies are forecast for Los Angeles and the en route weather across the Pacific gives no cause for concern. The captain notices, however, that a strong tailwind aloft will considerably cut his flight time to Los Angeles. He reads the Notices to Airmen (NOTAM) which are published by the local air traffic authorities notifying pilots of information pertaining to their flights. These tell of runway closures, unserviceable radio beacons, airspace restrictions for air defence exercises, taxiway works and other useful information that may have an impact on the flight.

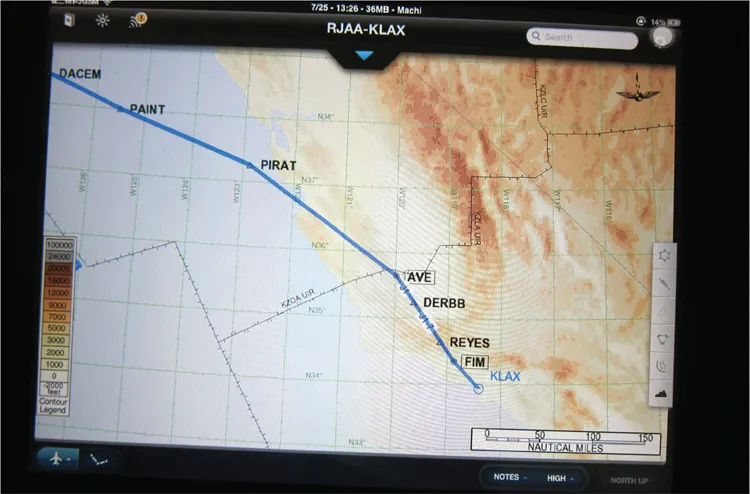

NOTAMs include daily published routings across the Pacific that are normally used for filing aircraft flight plans. On the evening prior to the next day’s operations, the air traffic management authority of the US, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), selects and publishes the most favourable parallel easterly tracks across the Pacific taking into consideration wind and weather patterns. These parallel tracks, 60 nautical miles (110km) apart, are plotted to capture the strong westerly polar jet streams that blow with wind strengths of up to 250 knots (kt) from the countries of the Far East to the Americas. These changeable tracks are known as the Pacific Organised Track System (PACOTS) and are published every day. Airlines take full advantage of these tracks, saving time and fuel on their easterly Pacific crossings.

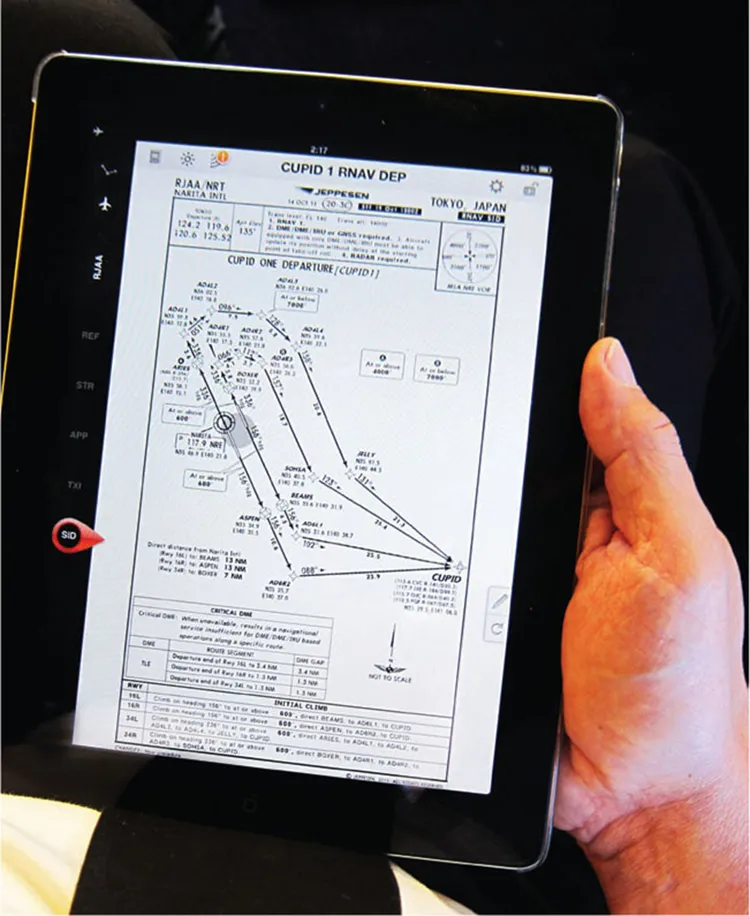

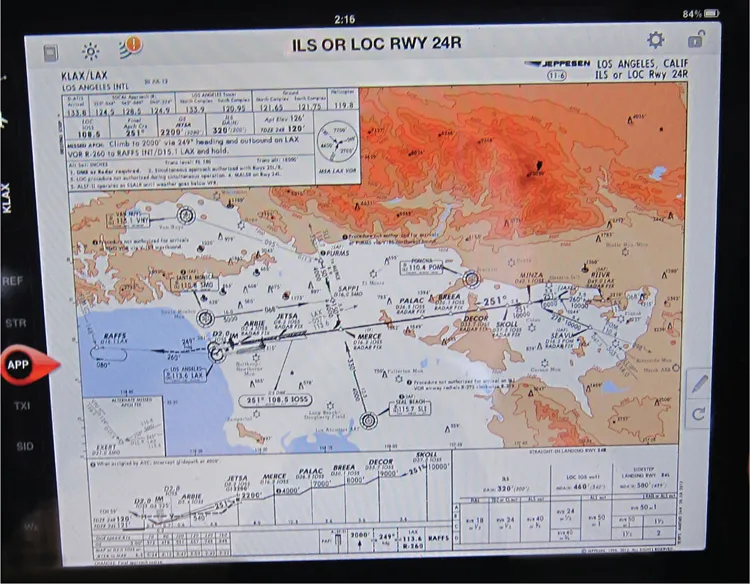

Opening the ‘Jeppesen App’ (application) with his password on his company-issued iPad, Captain Yakota transfers the flight route from the briefing package into the iPad application. The planned flight route is automatically plotted across the Pacific and the departure, arrival and alternate airport charts for Narita, Los Angeles and the alternate airport Ontario, California are loaded in ready for viewing. The Jeppesen airport charts offer guidance for taxiing, take-off and landing and are ready for display at a touch. The en route navigation charts are displayed with the flight routing plotted in. All relevant information, such as Air Traffic Control radio frequencies and other useful flight details, are highlighted for the different Flight Information Regions (FIRs) along the way.

The taxi drops Captain Yakota by the kerb in Narita’s Terminal One where he proceeds to a special crew-receiving counter to check in his suitcase. He then takes the elevator down into the lower levels of the Terminal One building and makes his way to the airline’s flight dispatch room. There he meets his crew, First Officer Endo and Captain Izumi. Although the 787 is a two-man operated aircraft, on this evening’s nine-and-a-half-hour flight, a relief captain is provided for in-flight rest with the three cockpit crew taking turns for a break during the long journey. As Skybird Airways is not a big airline, the three-man crew are familiar with each other having flown together on previous duties. After a quick exchange of pleasantries, they proceed to the flight dispatcher’s desk for a pre-flight briefing. Laid out there is the paperwork for the flight, which is the same briefing package that Captain Yakota had earlier viewed on his iPad while riding in the taxi. They discuss the various details pertaining to the flight with the flight dispatcher.

Earlier, three hours before the scheduled departure of the flight, the flight dispatcher at Narita operations would have drawn up a flight plan for Skybird 787. The dispatcher collects the necessary information such as the Notices to Airmen (NOTAM) from the Air Traffic Information publications, the en route and destination weather reports, the provisional passenger and cargo loads from the Traffic Office and the reports of the serviceability of the aircraft from Engineering. With the provisional Zero Fuel Weight (ZFW) of the flight, he enters the departure and arrival airport into a route search program. The route search program, taking into consideration the en route winds, scans for the most favourable published air traffic routings available and presents the best route options. The dispatcher then selects the ‘least cost’ flight routing from the options that are displayed.

The cost of the flight can be divided simply into fixed and variable costs. Fixed costs are crewing, catering and landing fees, while variable costs are the required fuel load, the time-based airplane usage charges and the Air Traffic Control (ATC) service charges along the route. ATC charges vary depending on the transit time through air traffic regions and the fees imposed by the regions’ governing authorities. Owing to the high cost of fuel, the selected routing is, more often than not, the one with the shortest flight time with the least fuel used. Ensuring that no bad weather is forecast along the way, the flight dispatcher chooses a route and files a flight plan with the Japanese Air Traffic Control (ATC) centre. With the flight plan to Los Angeles accepted, he compiles a briefing package with all the assembled information. The flight briefing package is then uploaded onto the company’s website, allowing the operating pilots to download and examine the flight details via the Internet before arriving at the airport.

At the briefing desk, the flight dispatcher briefs the crew on the forecast en route and destination weather. Referring to the en route airports between Narita and Los Angeles, he briefs that the forecast weather for them is favourable for a diversion if required. Included is the technical report provided by Engineering indicating that the newly delivered 787 has no significant engineering defects that may affect the flight. The dispatcher then highlights the appropriate air traffic NOTAMs for closer attention by the crew.

FUEL REQUIREMENT

The dispatcher informs Captain Yakota that he has selected the minimum flight plan fuel for the route and awaits his concurrence that it is sufficient. ‘Minimum fuel’ for a flight basically consists of the fuel required for the taxi and departure, the ‘burn-off’ en route and the fuel required for arrival and taxi at destination. In addition, contingency fuel amounting to 3 per cent of the ‘burn-off’ is carried in case of unexpected circumstances. Fuel to proceed to an alternate airport if the flight is unable to land at the destination, in this case Ontario California airport, with an extra 30 minutes’ holding is provided. The total of the above fuel requirements is the mandatory minimum fuel load for a flight. On today’s flight, as the twin-engine 787 will be flying over the vast Pacific Ocean for an extended period, it is a requirement that extra fuel is included in the mandatory minimum fuel load in case of an engine failure or cabin depressurization in a remote region. If an engine failure occurs, the aircraft would not be able to maintain cruise at the planned flight level with the loss of one engine and would be obliged to descend to a much lower altitude. In the case of a depressurization, the aircraft would also be required to descend to a life-sustaining altitude of 10,000ft. In both these circumstances the aircraft could not continue to destination, and with jet engines being less fuel efficient at a lower cruising altitude, additional fuel would be required. Sufficient fuel must be planned to ensure that an en route diversion airport can be reached at the lower altitudes.

In case of an engine failure in the 787 twin-engine aircraft flights over remote regions, it is a legal requirement to have a diversion airport within 180 minutes single-engine flying time from the planned routing. This procedure is called ExTended OPerationS (ETOPS) by the USA’s Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) or Extended Twin OPerationS (ETOPS) by the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and, just to add to the confusion, the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) calls it Extended Diversion Time Operations (EDTO). However, ETOPS is the most commonly used term and for today’s flight, the ETOPS en route alternate airports are Shemya in the Aleutian Island chain, Anchorage in Alaska and Vancouver in British Columbia. With the introduction of more modern and reliable engines, Boeing is trying to get approval to extend the 787 ETOPS to 330 minutes’ single-engine flying time to a diversion airport. This would enable the 787 to operate unhindered in more remote routes such as between the west coast of the USA and New Zealand.

The captain considers that, with no expected inclement en-route weather or air traffic delays at the destination, the flight plan minimum mandatory fuel is sufficient and no top-up of extra fuel is required. Taking excess fuel in addition to minimum flight plan fuel is always given careful consideration as extra fuel load is basically ‘dead weight’ and results in costs being added to the operation with part of the extra fuel being burned just to carry the excess. The captain has to assess the benefit of carrying excess fuel to extend his options if the destination weather forecast is poor. It could be that he arrives at an airport without any excess fuel, has to wait out bad weather by holding to land, and the flight would have to immediately divert. For today’s flight the captain approves the planned fuel load of 61,000kg (134,000lb) giving a planned take-off weight of 201,000kg (443,000lb), much less than the 228,000kg (503,500lb) maximum take-off weight of the 787-8.

With the fuel decided, Captain Yakota signs the fuel-order form and hands it over to the dispatcher, who then relays the fuel requirement to Engineering for refuelling. The fuel details are also relayed to the Load and Planning department which performs weight and balance calculations to ensure the aircraft is properly loaded. The disposition of cargo and passengers is also calculated and, to ensure that the centre of gravity remains within limits, with the aircraft balanced in all phases of flight, the aircraft loaders are notified of the proper distribution of cargo and passenger loads. All these details are displayed on a load sheet for presentation to the pilots prior to the flight’s departure. They will cross-check the figures and note the aircraft’s final operating weights and the position of the centre of gravity that is used to determine the setting of the horizontal stabilizer trim take-off position. After engine start, the pilots position the horizontal stabilizer to the calculated...