![]()

CHAPTER 1

The history of botanical and scientific illustration

Scientific illustrations first appeared in Alexandria, as long ago as the third century BC. Rendered on individual sheets of papyrus, these Hellenistic illustrations covered a variety of anatomy, obstetrics, surgery and botanical illustration of a medicinal value. Theophrastus (c.371–286 BC), known as the ‘father of botany’, wrote many books, including the 10-volume set, Historia Plantarum (‘Enquiry into Plants’). His curiosity led him to research and findings on germination, cultivation and propagation – amongst many other discoveries, which included the grouping of plants into categories. He was a student of Aristotle, the Greek philosopher and scientist, and is probably deemed as one of the earliest founders of botanical research.

Himalayan Balsam, Impatiens glandulifera.Scientific plant study.

Later on, in the first century AD, the first known copies of De Materia Medica (‘On Medical Material’) were produced, translated into both Latin and Arabic. These were written by a Roman physician of Greek origin called Pedanius Dioscorides. In this illustrated book he covered 600 plants with around a further 1,000 medicines made from them. It was widely read for thousands of years and was regarded as a pharmaceutical ‘bible’ for those in practice, becoming the most influential work on medicinal plants in both Christian and Islamic cultures. Astonishingly, a copy of the illustrated manuscript, dating back to the sixth century, is still in existence, held in Istanbul, Turkey.

THE VOYNICH MANUSCRIPT

The Voynich manuscript was written much later but is believed also to perhaps have some relevance to medicinal and herbal remedies, containing many botanical and medical illustrations. The most likely presumption is that it was perhaps deemed to have served as a pharmacopoeia or to give an understanding of medieval medicine. Either way it has proved to cause much intrigue over the years with its peculiarly written text in an unknown language and obscure unidentifiable illustrations.

Carbon dating suggests that the vellum dates back to somewhere between 1404 and 1438. However, the first records of this book were made in the early seventeenth century, and stylistic analysis of the illustrations suggests that it was written in Northern Italy during the renaissance period. Bought in 1912 by Wilfred Voynich, a Polish antique book dealer, the manuscript has since been studied by numerous amateur and professional cryptographers who believe the book contains a secret code. Many codebreakers have tried to unravel the extensive text and illustrations. The text, written using a quill pen, is arranged on the pages with the words reading from left to right, in an undecipherable language, although some parts are written in English, Latin and Chinese text; to confuse matters further there are no punctuation marks or alterations, just fluid writing.

As a botanical and scientific illustrator, the content of this book is rather fascinating, regardless of the crude nature of the drawings. The Voynich manuscript is divided into five (or possibly six) sections according to the illustrations: Herbal, Astronomical, Biological, Cosmological, Pharmaceutical and Recipes. Although the author cannot be identified, it has been established that the pigments for the paints in which the illustrations were rendered were not expensive. Out of the hundreds of illustrations throughout the book, only thirty-seven plants and six animals can be determined, including the ‘Wild pansy’ and the ‘Maiden hair fern’.

Bizarrely, many of the plant drawings are a jumble of roots from one plant species, leading to leaves from another and then flowers connected to a third. This has all added tremendous intrigue for codebreakers across generations, but the general consensus is that the Voynich manuscript is a hoax, written with little sense or distinguishable meaning. Whether there is an underlying code in the manuscript or not, what remains is an early, albeit inelegant, representation of botanical and scientific illustration that has been mostly preserved; out of the 270 original pages, 240 vellum pages still remain intact. Despite the inaccuracies and flaws, one can’t help wondering what possessed the author to write and illustrate a book of such depth, and what his motivation might have been in creating his own versions of the true specimens. Whilst there are still findings being made, it is hoped that one day the truth behind the Voynich manuscript will be uncovered.

RENAISSANCE ANATOMICAL AND MEDICAL ILLUSTRATION

Lavenders have been used as medicinal plants over many years; their oil is extracted and used to soothe a number of ailments including anxiety and insomnia. Commissioned by the Eden Project for the Lavender Garden.

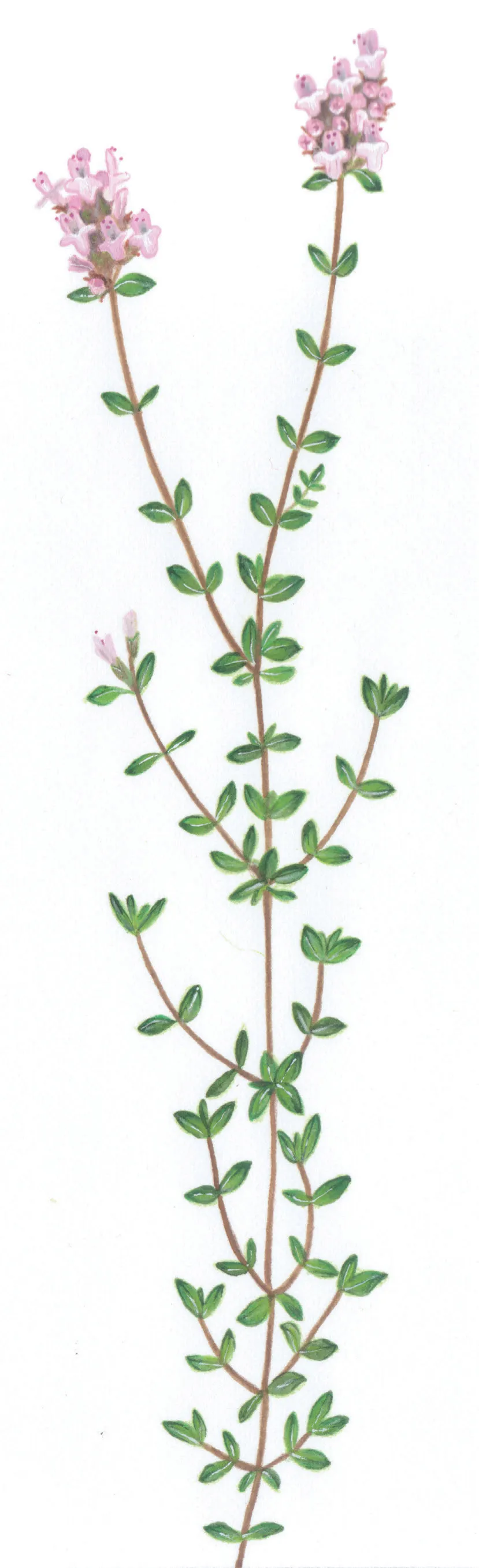

Thyme, Thymus vulgaris, is used for culinary and pharmaceutical purposes. Medicinally it can be used to aid stomach aches and other digestive problems. Commissioned by the Eden Project for the Mediterranean Biome.

During the Renaissance period Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was considered to be the pioneer of medical scientific illustrations. With over 800 anatomical drawings, he conveyed a superior understanding of scientific and anatomical studies, developing a new style of drawing that included cross-sections and exploded illustrations to convey a deeper understanding of his subjects. With his drive and passion to understand the complex workings of the human body, his findings were centuries ahead of his time; despite his genius, however, his work wasn’t actually printed until the nineteenth century.

Many artists of that period were intensely interested in anatomy; however, it was Leonardo’s sharp observations and accurate drawings that set him ahead of his peers. It was in the latter years of his life that his fascination with the heart and in particular the valves were explored and recorded through notes and drawings. He discovered the complex inner workings of the heart and its fundamental qualities as an organ pumping the blood in and out and in turn the opening and closure of the valves. Remarkably, this observation – made back in 1513 – wasn’t revisited until the twentieth century. To put this into context, a 2013 exhibition in the Queen’s Gallery in the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh displayed the sheets of Leonardo’s investigations alongside an MRI scan of blood flowing through the aortic valve, and with only minor discrepancies his theory was correct. Further exploratory tests at this exhibition showed many of Leonardo’s formulative theoretical sketchbook sheets were frustratingly close to what we know today as being the correct findings.

The scientific illustrators of the Renaissance period were recording anatomical and medical illustrations with new and macabre sources of reference. Some of the Renaissance artists specializing in anatomy were physicians and scientists also, with a thirst for knowledge. Although a little unorthodox, in the name of science (and curiosity, perhaps) they resorted to dissecting human corpses, rather than animal carcasses.

This practice undoubtedly took their understanding of the human anatomy to another level. Mostly they would be given the bodies of executed criminals, although in their obsession to observe and formulate theories some would go to more extreme lengths. Andreas Vesalius (1514–64), anatomist and artist, was reported to have begun a human dissection on a skull only to discover the attached body was very much alive!

With all of today’s resources – scans, X-rays and cameras – it is quite astounding to appreciate just how far medicine has come on since those early days. Whilst what would seem almost grotesque in the dissection and drawing of putrid deteriorating bodies, and those of the diseased and deformed, it was the staggering efforts of those early artists and physicians that has moved medicine and treatments forward. Were these scientists dabbling with art, or indeed were they artists trying to understand science? Whatever the answer, this rather wonderful melée of art and science still holds a deep fascination today.

As with many of their predecessors, physicians and surgeons of the nineteenth century built close relationships with scientific artists. For the Renaissance physicians and artists the collaboration was deemed more of an elite enlightenment of medicine, an understanding of the relatively unknown. Although macabre in content, anatomical drawings provided mesmerizing intrigue to the anatomist, who could view plates of the inner workings of the body in precise still detail.

The microscope was invented in 1590, and gave great insight into the study of plant anatomy and intrigued physicians, although until many years later it was perhaps perceived as something of a novelty. In the nineteenth century the European physicians began to touch on the developments of the first achromatic microscopes and the first permanent photo etching, invented by Nicéphore Niépce. This allowed the physicians and surgeons a deeper level of accuracy in their research and, one could argue, a challenged perspective of how anatomical art should be visualized. Although perhaps horrifically graphic to many outside the medical profession, to those with a curious mindset the cut-away internal sections of the body, including those of diseased and sick patients, gave tremendous clarity. The cross-analysis between the laboratories studying bacteriology, for example, and the artist being able to visualize their research as an illustration, helped the practitioners of scientific medicine to make significant progress.

Developing an understanding of the human form, and the anatomy within, is a great practice for any artist. Life drawing classes can be hugely beneficial for learning many techniques.

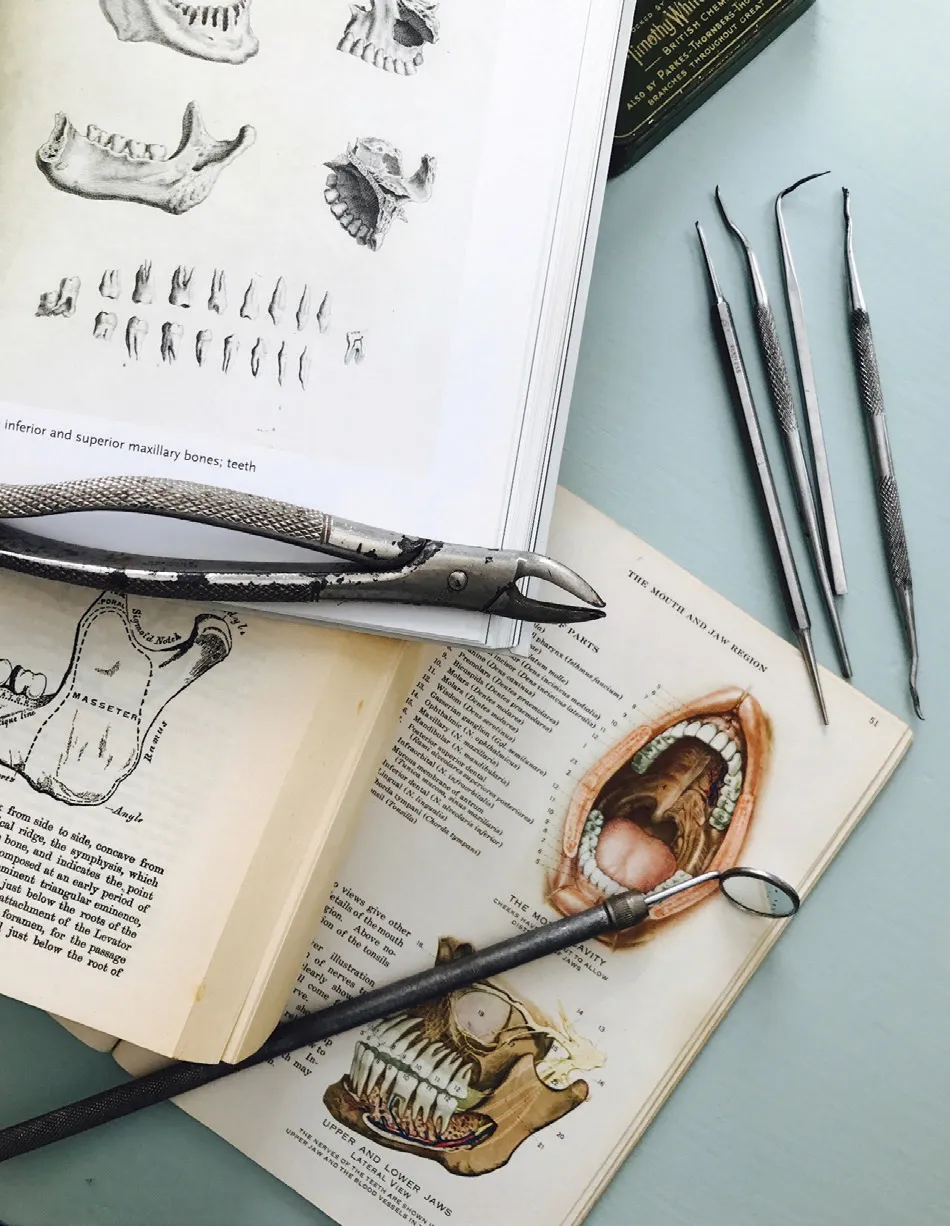

Books of anatomy and dentistry tools from the early nineteenth century.

Limited editions, printed and bound on exquisite, fine papers in oversized books, were the first publications but, as time moved on and the numbers of medical students increased, more inexpensive books were made. It must have been quite a feat of expertise and teamwork to make each and every medical illustration, starting with the corpse, to the pathologist on advice from the surgeon or physician on the matter of where to dissect. The dissected section would then be prepared for the illustrator to make the initial drawings, carefully recording colours and textures for the engraver to make either copper plates or woodblocks as true to the specimen as possible. Sensitive drawings publications but, as time moved on and the numbers of medical students increased, more inexpensive books were made. It must have been quite a feat of expertise and teamwork to make each and every medical illustration, starting with the corpse, to the pathologist on advice from the surgeon or physician on the matter of where to dissect. The dissected section would then be prepared for the illustrator to make the initial drawings, carefully recording colours and textures for the engraver to make either copper plates or woodblocks as true to the specimen as possible. Sensitive drawings closely together would ensure the best results and the finest artworks that we still see in print today.

A perfect example of this wonderful collaboration was between the anatomist and surgeon Henry Gray, and Henry Vandyke Carter, artist and surgeon-apothecary from London. Together in 1858 they produced Anatomy Descriptive and Surgical or, as it more commonly known today, Gray’s Anatomy. What with staggeringly beautiful detailed illustrations and complex informative text to complement it is no wonder it went onto become probably the world’s best known medical book. Keeping pace with technology, apps have been made from this original book for students.

HERBAL ILLUSTRATION

Herbal illustrations, although being some of the earliest known type of botanical illustrations, are not actually found in print until the fifteenth century when the first printing presses were invented. Their purpose would largely have been to aid apothecaries in making up prescriptions for physicians. Beyond the medicinal use, herbal illustrations depicted by physicians and natural historians of the sixteenth century were appreciated many years later as a creative art form, becoming the inspiration for some of the most exquisite floral fabrics and wallpapers of William Morris.

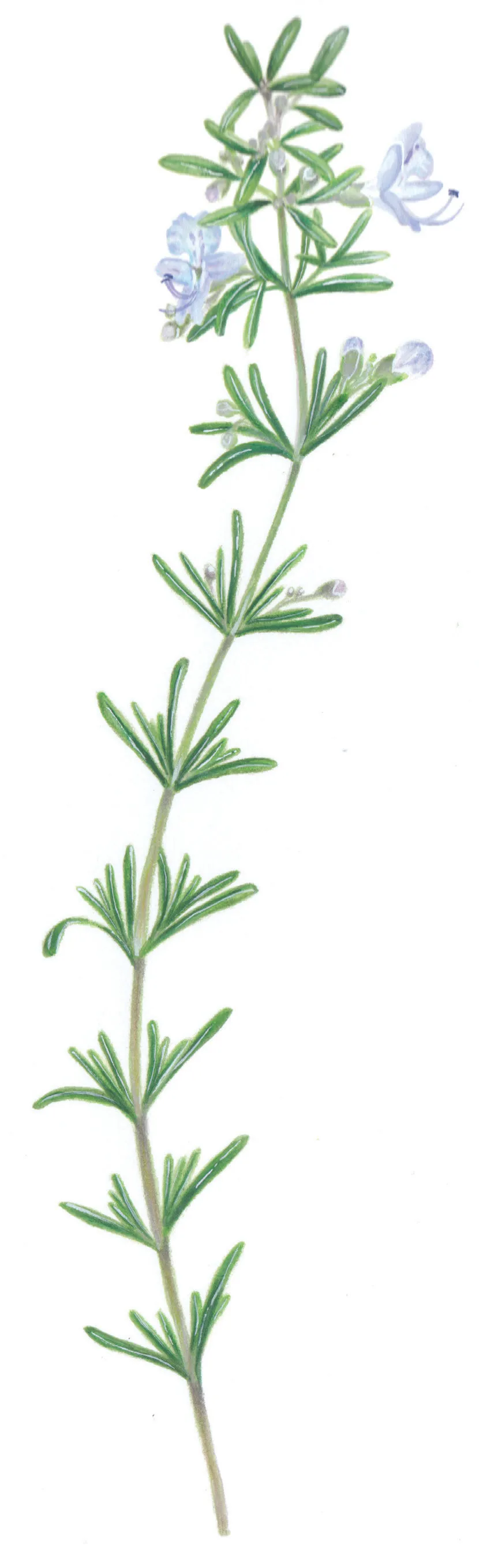

Rosemary, Rosmarinus officinalis. An incredibly useful plant in the kitchen, it also has medicinal uses: it is an ...