CHAPTER 1

AN INTRODUCTION

TO MOLE CATCHING

Mole catching as a tradition is fast fading into the mists of time because few people have the skill or ability to understand the mole in the complex world in which it lives. Others attempt and some succeed to control a mole but at what costs and circumstances? The traditional mole catcher could be seen wandering across a field or down a shady lane, a bag on his shoulder and not a care in the world. Today, life for mole catchers remains slow. With no one to correct or instruct them, only an isolated few have the knowledge necessary to be called a ‘mole catcher’. There are people who can catch the occasional mole, and it is often claimed that gardeners are as good as any mole catcher, but certain skills are necessary before one can truly earn the name ‘mole catcher’.

Mole catchers catch moles anywhere and everywhere. Gardeners catch them only in the gardens they work in, in a setting that rarely changes and in conditions that dictate little. A mole catcher will visit many locations with different features and soils, and where the general environment makes many demands on the mole. These differing, and changing, conditions will test the skill and knowledge of the mole catcher.

Nowadays, pest control companies undertake mole control, but how many in today’s profit-driven economic market can claim to offer the results and service of the traditional mole catcher? Traditional mole catchers are paid by result. Historically, ‘no mole meant no pay’ and for centuries mole catchers have had to produce a mole as proof of the completed task and to receive payment. Many of today’s disposal methods only offer a person’s word that the mole has been removed – should another mole appear there is no way of knowing if it is the same mole or a different one. Mole catching is, in my opinion, the most humane way to be rid of a mole. Mole catching employs the use of kill traps and ensures a quick dispatch of the mole. I find it strange that in today’s modern world there are so many inhumane attacks on the mole. We often proudly claim to be green and environmentally friendly. However, when a mole appears in the lawn and begins fly-tipping, the list of substances that are pushed, poked and pumped into the mole’s environment is endless, and the results are not guaranteed. The mole spends all day dodging this, squeezing past that and putting up with all kinds of obnoxious smells. Sometimes so much environmental effluent is stuffed down into the mole’s abode that it is forced to take a holiday in order to conserve energy, which will be needed upon its return to dig new tunnels in the only remaining part of the prized lawn not to have been destroyed in man’s efforts to be rid of this little man in black.

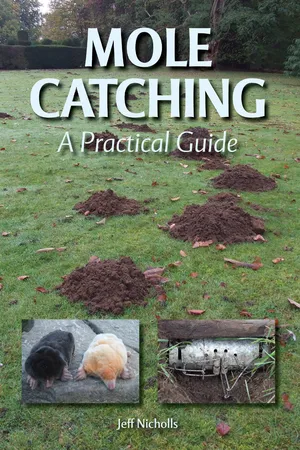

A MOLE CATCHER’S TRAPS

Mole catchers have always used traps, but I have often seen people cringe at the word ‘trap’. Traps conjure up visions of large metal devices that maim limbs and prolong suffering prior to death, but this is not the case. Traps catch by design and are authorized by the relevant authorities to carry out the task required, and only mole traps can be used in the mole environment. Many traps have been banned because they kill, maim and torture many targeted and non-targeted species, including humans. The definition of the word trap – ‘to deceive or ensnare’ – does little to change people’s perception of how a mole trap works. Perhaps if the definition were changed to ‘a quick and effective method of control’, people would find traps less repellent. It is important to remember that traps are only effective and safe when used properly.

HOW MOLE CATCHING HAS CHANGED OVER THE YEARS

Mole catching has changed little over the centuries. We know that moles plagued the Roman Empire from the earthenware pots excavated from Roman sites. These earthenware pots were used as traps. They were buried in the mole runs and part filled with water; when the mole fell in it would drown. We may never know if this was the work of mole catchers all those years ago, but the buried pot method has been used until recently around the country, possibly all round the world. I wonder how many excited archaeologists have wondered at the find of a lonely pot in the earth – a pot with a small hole in the side that would allow any fluid to escape at a measured depth. The pot required this overflow to prevent the mole from scrambling free from a naturally overfilled pot. These pots were relatively large at 12in (30cm) deep but enabled more than one mole to be caught. They were operated by a trap door in a piece of wood laid across the top, which the mole fell through when the pot had been successfully placed in a main tunnel. The mole catcher employed by the early English kings would have used this method as many of the royal estates and manors engaged a mole catcher.

Mole Fact File

The old name for a mole catcher is a ‘wanter’ or ‘wonter’.

Earthenware pots progressed to clay barrel traps – a tube made from coarse earthenware, which was a mixture of clay and ground-up fired pots known as grog. The traps were designed after consideration to the mole’s own natural environment – tunnels – and made from a mould. Although some mole catchers may have made their own, the local potter was always to hand. The clay barrels were made to no fixed size, and I have different dimensions for these traps from the same family of mole catchers. They were approximately 6in (150mm) in length and between 2in (50mm) and 2½in (60mm) in diameter. Two grooves cut internally at each end held snares that were used to catch the mole. Two holes in the top of the trap above these grooves allowed for a string or wire to form these snares. A third middle hole was for a peg, which was the trigger that released the trap. To enable a mole to be removed from the trap, a V-shaped cut was made to the underside of the trap body. By researching genealogical dates of the people who used these traps, it was found that the traps were used during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and long into the nineteenth century. They were the first of a series of traps that were powered by a bent stick, which I will cover later. The snares were merely a loop tied in each end of a wire or string, which sat in the groove in the trap. Another string was passed through the middle hole and tied between the snares. This allowed the snares to close and pull any mole up to the roof of the trap. The middle hole was plugged with a small peg that, with the middle string passed through, would prevent it from being pulled through unless the peg was removed. The removal of this peg by the mole was the trigger that operated the clay trap. These clay barrel traps were an advance in mole catching, but they were easily broken underfoot by both animal and man. The harsh conditions in which these traps were used also demanded a stronger material.

Another traditional village craft – that of the wheelwright – provided a solution to the problem. Cartwheels were required to withstand extreme workloads in all weathers, and soon the mole catchers were using wooden barrels to replace the weaker clay. The wheel hubs were made from elm, a timber that is strong but, more important, resilient to moisture. They were exact copies of the clay barrel in size and operation. The wheelwright – or sometimes the ‘bodger’ – like the potter could provide the body of a mole trap for the mole catcher, but the costs of these craftsmen dug deep into the mole catcher’s hard acquired money.

Many mole catchers began to construct their own mole traps from materials collected from the copse. These homemade traps were very similar to the metal half-barrel traps I use today. Most homemade traps were constructed from a piece of wood, two small hazel sticks, a twig for a nose peg and a length of string. The piece of wood needed to be approximately 6in (150mm) × 2in (50mm). The thickness was not important but rarely exceeded ¾in (20mm).

This piece of wood formed the top or roof of the trap. Five holes were drilled in it – one at each corner and one in the middle to hold the nose peg, also known as a mumble pin. Mole catchers often added notches and their own individual marks. When I first made my own, I carved a pattern around the edge.

Hazel wood was often used because it is such a forgiving tree; the cutting promotes growth, which can be used as required. The hazel sticks were no more than the thickness, and the length, of a pencil. These were whittled down using a sharp knife to the soft centre core which, when scraped out, provided a neat groove for the string to sit in. The sticks then required bending to form the loops that would hold the strings and form the legs the trap rested on. Steam from a boiling kettle or pan was applied to the middle of the sticks until they became pliable. They could also be made pliable by soaking in water. They could then be bent slowly to form the shape of a horseshoe. A block of wood and a few nails were used to hold the sticks in this shape until they dried; some bent them round a pole. Once dry, the stick was cut to the size needed to allow the mole to pass through. This was about 2½in (60mm) for the loop and a little extra to be glued in the piece of wood when it was all put together.

The horseshoe-shaped sticks locate in the four corner-drilled holes and glue holds them tight. The string is threaded down one corner hole, squeezing past the stick, and is then pushed up out the other hole at the opposite corner. A knot is tied and the resulting loop catches the mole. The other end of the string is tied similarly at the other end of the trap. The trap then consisted of a loop of string at each end, which was laid in the natural grooves of the sticks. The string loops tied at each end of the piece of string meant that when the middle of the string was pulled, both loops operated upwards. (Some mole catchers used a copper wire instead of string to form these loops.) The finished trap now had to be powered. This was achieved in the same way as its forerunners, the clay and wooden barrel traps – with a bent stick often referred to as a bender. The bender stick was also used for powering snares for rat trapping. These sticks – often as many as three were used to power a mole trap – were approximately 4–5ft (1.2–1.5m) in length and flexible. Willow, hazel or another suitable wood was employed. Allowing for the depth of mole run the trap was to be used in, another piece of string was tied central to the string containing the two loops. A tail on the knot used to join these strings was pushed through the middle hole in the piece of wood and held in by the nose peg or – to give it its proper name – the mumble pin. At this point, the trap could be suspended by this new piece of string without the loops being disturbed. When the...