![]()

1 | introduction and model history |

Between 1958 and 1985, more than a million Series II, IIA and III Land Rovers rolled out of the Solihull factory. Simple, rugged and durable, they have survived in very large numbers and many are still working hard for a living in almost every country in the world. But with the oldest survivors fast approaching their sixtieth birthday, the vehicles are now rightly regarded as true classics to be cherished and admired. The aims of this book are to help you to select the Series II, IIA or III Land Rover that is right for you, to keep it running the way Solihull intended and, perhaps, to upgrade and modify it to make it more usable in modern traffic conditions. You will also learn how even the most battered and neglected old Land Rover can be restored to its former glory.

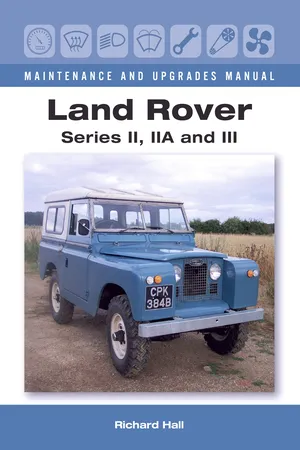

The classic Land Rover: 1964 Series IIA hard top, freshly restored in Marine Blue.

The first vehicles to bear the Land Rover badge appeared in 1948, and the range that was produced between 1948 and 1958 is now known retrospectively as ‘Series One’. The vehicle was conceived as a stop-gap model for the Rover car company in the austerity years that followed the Second World War. Materials of all kinds, and especially steel, were in short supply, and car manufacturers producing vehicles for export markets tended to be favoured by the Government when it came to allocating resources. Rover had little to sell other than large, luxurious saloon cars of pre-war design. The company needed a new product, and fast.

And so the Series One was born. Intended to supplant the cast-off wartime Jeeps that had proved so popular across the world, the new model was built along very much the same lines as the Jeep: separate chassis, strong solid axles mounted on leaf springs, four-wheel drive, plenty of ground clearance for rough terrain and the minimum of creature comforts. Rover envisaged selling just a few thousand Land Rovers to keep the factory busy until the launch of the new ‘P4’ saloon car, so the body shape was kept simple: mostly flat panels riveted together at right angles, requiring the minimum of costly press tools. Bodywork was largely aluminium, which was easier to obtain than sheet steel. Major mechanical components, including the engine and gearbox, were ‘borrowed’ from other models in the Rover range.

It is fair to say that the company underestimated the demand for its new utility vehicle. Within a year, the vehicles were being snapped up as fast as Rover could build them, and users were demanding more – more power, more reliability, more comfort, more load-carrying capacity. Solihull did its best to respond with bigger engines, stronger suspension, long wheelbase and five-door Station Wagon variants, but the essential problem remained: the Series One simply was not designed for high-volume mass production or for the kind of routine overloading and rough treatment to which it was now being subjected. The company needed to do something drastic.

In March 1958, the ‘Series II’ Land Rover was launched. It was bigger and sturdier than the Series One, with a new petrol engine giving 50 per cent more power than the old one. It had more load-carrying space, strengthened mechanicals, better brakes and a new body shape by David Bache, Rover’s in-house designer. Similar at a first glance to the Series One, the new body featured curved upper sides of much greater depth, and was so successful that the basic shape can still be seen in today’s Defender. In fact, you can take the doors from a brand new Defender and bolt them onto a 1958 Series II, if you so wish.

The Series II was available from the start in both long- and short-wheelbase variants, with a choice of petrol or diesel engine. An all-new and strikingly handsome five-door Station Wagon followed a year later, its clean lines a sharp contrast to the Series One Station Wagon, which looked as though it had been pieced together using several different vehicles and a large Meccano set. The new model was an immediate success, with annual sales climbing from around 25,000 in the last full year of Series One production to 35,000 by 1961.

That year saw the introduction of a more powerful diesel engine to replace the rather feeble Series One-derived unit, and the change (along with a few minor cosmetic improvements) was considered important enough for Solihull to designate the new model ‘Series IIA’. Sales continued to increase, helped by the addition to the range of a more powerful 6-cylinder engine option in 1967, and a round of modest (but welcome) improvements to the interior and electrical systems in the same year. In 1969, the headlights were moved out to the front wings to comply with new legislation, but further changes were just around the corner.

By the late sixties, Rover was running into problems. In overseas markets, the Toyota Land Cruiser was starting to eat away at Series IIA sales. Like the original Land Rover, the Toyota was inspired by the wartime Jeep and had many of the same attributes. It had beam axles, leaf springs, four-wheel drive and a simple, rugged construction. Its all-steel body corroded rapidly in damp climates, but in the Australian outback or the South African veldt that was of little consequence. What mattered was that it had a far more powerful engine than the Land Rover, could carry heavier loads and very rarely broke down. By 1965, Toyota had sold 50,000 ‘J’ series Land Cruisers; in 1968, total production topped 100,000. Land Rover might still be selling three Series IIAs for every Land Cruiser, but the Japanese rival was catching up fast.

A new model was needed to replace the Series IIA, but by now political events had intervened. In 1966, Rover had merged with Leyland Motors, a successful and profitable manufacturer of heavy commercial vehicles, which already owned Rover’s great car-making rival, Triumph. The Government’s policy of the time was to strongly encourage consolidation within the car industry, and so when British Motor Holdings (owners of Jaguar, Austin and Morris among others) ran into financial trouble two years later, Leyland was prevailed upon to combine with the loss-making giant to form British Leyland.

Red knob, yellow knob: astonishing off-road performance on demand.

Made in Solihull and proud of it.

From now on, any new Land Rover product development would have to compete for limited funds with the high-v...