The Smith-Dorrien–French Feud

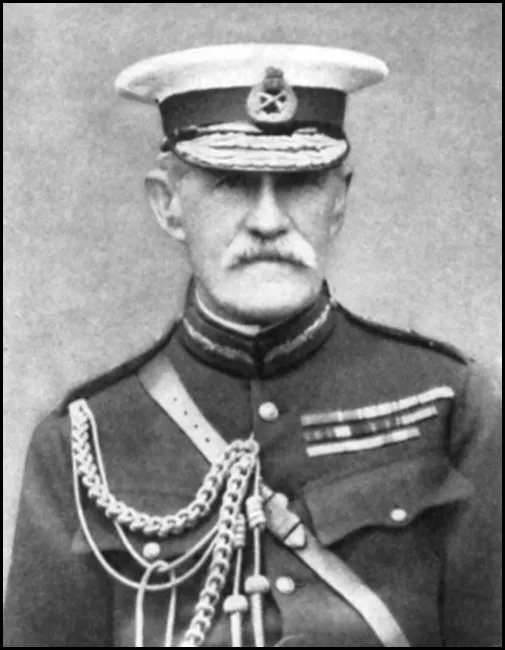

Horace Smith-Dorrien was born into a large, upper-middle-class military family in Hertfordshire in 1858. The family was not rich; at his death in 1930 Horace’s estate was valued at £6,519 3s. In many respects his career followed the conventional pattern of a late Victorian officer: after Harrow School he was commissioned into the 95th Foot (later the Sherwood Foresters) and attended the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. By 1879 he was fighting Zulus at Isandhlwana, and in 1898 he was fighting the Mahdi’s army at Omdurman. In between there were long spells playing polo in India, where it is said that he could remember the names of all the officers in his division as well as of their polo ponies. At Staff College, Camberley, in 1887 he was said not to know where to find the library but he still managed to pass his final examinations. He married late, as was usual for regimental officers at the time, in September 1902 at St Peter’s, Eaton Square, London, to Olive Crofton, also from a well-connected military family. By this time he might have considered that his period of active soldiering was coming to an end. He had, after all, just returned from three bruising years fighting the Boers, for a time as a brigade commander under Lord Roberts. In 1912 he was promoted full general and given the prestigious appointment of Southern Command. There he was when war broke out on 4 August 1914 and there he remained when the BEF sailed for France. As a lieutenant general there were in effect only two jobs open to him with the BEF and both those were taken. He was fifty-six years old with three boys under ten and devoted to his wife. But he was unlikely to stay on the home front for long.

But that is not quite the whole story of his pre-1914 career. Even as a young subaltern he had displayed considerable organizational skill, which had come to the attention of his superiors, and it was this skill that saved his life. When Col Durnford’s redcoats were being cut down by the Zulus at Isandhlwana, Smith-Dorrien was with the transport wagons distributing ammunition. He was dressed in blue patrols: for some reason this made him a less attractive target for the Zulus (all those who got away were wearing blue) and he managed to make off on horseback and then on foot after some useful work with his revolver. Fifty-six European soldiers escaped and 626 were killed, all with assegais. Smith-Dorrien undoubtedly helped some soldiers to safety. There was talk of a VC but it came to nothing.

At Aldershot Sir Horace succeeded Sir John French to the command and he – together with Haig as his successor, according to historians of the period – made possible the very high standards of the professional BEF that went to war in 1914.

As with all feuds, the origins of that between French and Smith-Dorrien are obscure. Perhaps French didn’t even need a reason to develop a phobia; in any case the mere fact that Smith-Dorrien, an infantryman, had had the temerity to put forward views on the tactical role of cavalry that were opposed to Sir John’s was reason enough. But he did more than just put forward views: he insisted that cavalry officers learn infantry tactics. Smith-Dorrien had, of course, done nothing more than join the reforming wing, led by Lord Roberts, in the debate over the role of cavalry, against the arme blanche led by French. There was also the matter of military police patrols in Aldershot: Smith-Dorrien stood them down to save troops from harassment, which made Sir John more than usually red-faced.

The feud was common knowledge in the Army. Although not a martinet, Smith-Dorrien himself was not exactly placid; his temper has been variously ascribed to bad teeth and to the fact that he was born eleventh of fifteen children. Always smartly turned out himself, he does not have the reputation, which Allenby of the cavalry has, of being a stickler for correct dress at all times – indeed, Allenby was known among the troops as ‘chin-strap’ for his obsession with this item of equipment. Smith-Dorrien was careful with money and faithful to his wife, both virtues not shared by French. Although he was not an intellectual soldier like Wilson or Lanrezac, his writing – like his actions – display a clarity and robustness that should be the envy of many an academic, although his diary, written at the behest of the King, is unfortunately free of indiscretions. The feud was already well entrenched by August 1914. We should note here that Haig and Smith-Dorrien were also on opposing sides in the cavalry debate. The British Army, like the French, was riven with schisms concealed as doctrinal debates, and promotion was often largely a matter of hitching one’s career-wagon to the most promising star.

During the winter of 1914–15, like many senior officers, Smith-Dorrien would become concerned about the growing number of cases of deserters found behind the lines and the effect these might have on the morale of front-line troops; he was invariably in favour of the death penalty in such cases. It is perhaps for this attitude, his upper middle-class background and his polo-playing that Stephen Badsey has called him a ‘fairly typical’ general of his generation. But it is a surprising and unhelpful description.

The feud went public with the publication of an interview (conducted by telephone) with Smith-Dorrien in the Weekly Despatch of February 1917, and became a central feature of French’s book 1914 (published 1919) to which Smith-Dorrien quite justifiably replied in a privately published statement. The feud centred around the events of the first week of hostilities and, in particular, the decision to offer battle at dawn on 26 August. The battle fought that day was to cast a long shadow.

The Battle of Mons

On 17 August 1914 Sir James Grierson, commander-designate of Second Corps, died of a heart attack in a train on the way to the front – he was extremely corpulent and his dining habits were lavish even by the standards of Edwardian cuisine. It was a loss universally felt, not least because Sir James was an acknowledged expert on the German Army and order of battle; he had been a guest of the Kaiser at the annual German Army manoeuvres. Kitchener sent for Sir Horace despite French having asked for Sir Herbert Plumer; this was not entirely surprising, Sir Horace being a protégé of Kitchener’s. On the 18th, Sir Horace shook hands with the King, with whom he was on familiar terms, bade farewell to his family and by the 20th he was in France. His fellow lieutenant general was Sir Douglas Haig, commanding First Corps. He took with him his personal staff officers: Major Hope Johnstone AMS, Capt W.A.T. Bowly ADC and Col W. Rycroft AQMG. At this stage, by his own admission, he knew next to nothing of the situation at the front. He confessed no feelings of personal self-doubt at the prospect of being in command of nearly 40,000 men under a commander-in-chief in whom he had less than full confidence, although he did not share Haig’s robust certainty of a direct connection with the Lord God of Hosts. It was now his manifest duty and destiny to fight the invading German armies of the German Empire, which by its ‘evil machinations’ was seeking to achieve hegemony over Europe by military power.

By the 21st he was at Corps HQ at Bavai to meet his chief of staff, Brig-Gen Forestier-Walker, followed by a meeting with the chief at Le Cateau. Here he got the general impression that Second Corps was to move up to the line of the Mons–Conde canal with a view to pushing on beyond it in a right wheel. By the 22nd his staff had set up HQ at a modest manor house at Sars-la-Bruyère, 6 miles (10km) south-west of Mons. It had no telephone but the Royal Engineers later fixed up a telegraph connection with GHQ. That afternoon he motored round the outposts and was not happy with what he found: a thinly-held front of 21 miles (33km) with poor fields of fire and the indefensible town of Mons in a salient. The canal was almost as much a hindrance to the British as a barrier to the enemy. He reconnoitred a fall-back position: in his heart he knew that there was no prospect of any offensive action by Second Corps. But he slept the sleep of the innocent that night; it was the last good night’s sleep that he, or indeed anyone in the BEF, was going to get for a long time.

At 0600 the next day French turned up at Sars and a conference of the divisional generals of Second Corps (Gen Hamilton of 3rd Division, Gen Fergusson of 5th Division and Gen Allenby of the Cavalry Division) met to hear the latest intelligence reports and to receive orders: the BEF was faced by no more than two German corps; Sir Horace was to move forward, stay put, or fall back if necessary. Sir Horace’s second line seemed to meet with the Chief’s approval, as far as he could tell. And with that Sir John went back to Le Cateau, via Valenciennes to inspect the recently arrived 19th Brigade. He was thought to have been ‘on splendid form’. Smith-Dorrien ‘chafed’: by that time the Battle of Mons had already started in earnest. At the end of the day, the first European battle for the British for ninety-nine years, the German buglers sounded ‘cease fire’ and two British divisions had stopped six German. First Corps under Gen Haig had not been engaged, but had stood sentinel on the right flank, facing east and north.

Command and Control

It was not the custom in the early twentieth century for army commanders to share the same physical dangers that their men suffered, although corps, division and brigade commanders certainly did on occasions: fifty-seven officers in the Great War of the rank of brigadier-general and above were killed by enemy fire. A shell burst in front of Sir Horace’s car at Mons early on the 23rd and he was within range of German shell-fire on the 26th. All of the division commanders came under shell-fire on that day as they rode out to the front lines, and lieutenant colonels were nearly as likely to be killed as their men, as were the brigadiers. Von Arnim, the equivalent of a brigadier in the British Army, was killed at Le Cateau on the 26th. Gen Franchet d’Esperey, a corps commander, led a brigade into battle at Guise on 29 August. Haig, while commanding First Corps, famously rode up the Menin road during the height of First Ypres. Von Kluck himself, exceptionally, had a brush with French cavalry just before the Marne battle and was badly wounded by a shell in 1915. All could have been killed.

Wellington, in the thick of the action at Waterloo, very nearly suffered the same fate as Sir John Moore at Corunna. By the time Lord Raglan was commanding in the Crimea, however, or Grant and Lee in the American Civil War, commanders at army level were acting in the role of managing directors rather than line managers; Lord Raglan was as likely to be killed by Russian action at Balaclava in 1854 as Sir John French was to be killed by German action at Mons, even allowing for the fact that Raglan was ordering individual units into action. The problem for army commanders, now that they were more distant from the battle itself and no longer concerned with tactics, was that communication technology had not kept pace with the growth in the level of organizational complexity: armies were now counted in hundreds of thousands, yet all movements had to go through the appropriate chain of command, by one method of communication or other.

In northern France in 1914 there was a partial and unreliable telephone system. Even a town as big as Bertry, say 5,000 people, might have only a single telephone. There were the army signallers (Royal Engineers) who could only do so much with their cables. There was as yet no effective mobile wireless system; the telegraph needed a transmitting station and a receiving station. The BEF had no despatch riders. What it did have was the RAC Corps of Volunteer Motor Drivers, among whom were the Duke of Westminster (known as ‘Bendor’) and Lord Dalmeny. Six of these aristocratic gentlemen, including the duke, were attached to GHQ at Le Cateau, driving staff officers to liaison meetings at corps and division HQs. They were of course driving their own cars, all of which had passed a technical inspection by the RAC.

The unavoidable truth was that even a distance of around just 20 miles (30km) from BEF HQ to its constituent corps was too far for effective communication, especially when the roads were clogged with military and civilian traffic; most roads were in any case in those days hardly designed for motor traffic. No one has imputed cowardice to Sir John, but both at Le Cateau and at St Quentin he was a little eager to move south, more so at St Quentin. Both moves were to inconvenience Smith-Dorrien, a man who was easily irritated by his C-in-C. Army commanders such as French made do with what communications they had with the knowledge that the telephone wires were not secure from enemy interference. This knowledge, combined with the fragmented and partial signals net, meant that in practice movement orders were issued in general terms, the details to be worked out by commanders on the ground (known as the ‘umpire’ system). Spy mania was at its height, but a staff officer in a Rolls-Royce driven by Hugh Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster, was about as secure as you could get as a means of communication. The main danger to drivers behind the lines, particularly in the French area of operations, was ‘lunatic’ Territorials or even civilians, armed with shotguns, who set up road-blocks in their hunt for ‘spies’. At times, interpreters were kept from meetings for fear of security leaks. Here is Lt Gen Sir William Robertson qmg on the means of communication on the Western Front:

In August 1914, although Sir John could n...