![]()

1An Introduction to Palaeoart

‘ The ordinary public cannot learn much by merely gazing at skeletons set up in museums. One longs to cover their nakedness with flesh and skin, and to see them as they were when they walked this earth’.

HENRY N. HUTCHINSON, 1910

Most people are aware that palaeontologists, the scientists who study extinct life, sometimes work with artists to produce works of art featuring ancient species and landscapes. The details of this process are mostly murky in the public sphere however, being rarely discussed outside of specialist venues and of seemingly little interest compared to finished illustrations, paintings, sculptures or animations of fossil creatures. In fact, there is a whole discipline for this form of artistry, replete with its own specialist knowledge base, skill sets, recognized artists, and a long history, all dedicated to the recreation of extinct animals, plants and their landscapes in illustration and scupture. This discipline has been variably named over the last two centuries, but is best known today as ‘palaeoart’ (Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1 The Cretaceous dromaeosaur Microraptor gui restored eating a fish (Jinanichthys). Every detail of this painting is based on fossil data, including the plants and environment, the depicted behaviour, and even the colour of the Microraptor, making it a supreme example of the genre known as ‘palaeoart.’ (E. Willoughby)

The terms ‘palaeoart’ (sometimes spelt ‘paleoart’ – this reflects the American-English spelling ‘paleontology’ instead of the English spelling ‘palaeontology’) and ‘palaeoartist’ were created by celebrated palaeoartist Mark Hallett in his 1987 article The Scientific Approach of the Art of Bringing Dinosaurs Back to Life. The term is a portmanteau of ‘palaeontological art’, palaeontology being the scientific study of extinct life and fossils. Somewhat confusingly, ‘palaeoart’ is also used in archaeological literature to refer to artistic creations by prehistoric people. An alternative term for art of reconstructed fossil animals, ‘palaeontography’, has been coined by another artist, John Conway, and might offer a solution to this confusion. ‘Palaeontography’ is used in some circles, although ‘palaeoart’ remains the dominant term by far and will be used throughout this book.

Fig. 1.2 The sea dragons as they lived, a classic palaeoartwork from 1840. (R. Martin)

While the discipline of palaeoart was only recently named, its history extends as far back as palaeontological science itself (Fig. 1.2). The first ‘modern’ piece of palaeoart – a sketched restoration of Pterodactylus antiquus, a Jurassic flying reptile – dates to 1800 and was produced for private correspondence between scholars. In the next half century, palaeoart entered scientific literature, was then used as an educational device for students, then to educate the public, and eventually as the basis for merchandising opportunities. Initially practised by scholars themselves, natural history artists began to enter the employment of scientists to facilitate the production of grander and more technically accomplished artworks early in palaeoart history. This relationship between scientists and artists continues today. We can thus essentially see the origins of our modern palaeoart industry – a tool for scientific, educational and commercial application – dating back to the 1850s, over 160 years ago. In that time palaeoart has undergone several movements and reinventions, shown a steady increase in popularity, and is now recognized as one of the most important assets in the popularization of palaeontology and scientific outreach.

Fig. 1.3 Bait Ball. Unnamed ichthyosaurs chase thousands of Thrissops into a bait ball, and cause panicked Trachyteuthis belemnites and Pectinatites ammonites to flee. Marine scenes have a long history in palaeoart, and represent some of its most evocative artworks. (B. Nicholls)

The skills and knowledge required to practise palaeoartistry take a long time to attain. It requires a great amount of scientific knowledge to understand data presented by a fossil specimen, the environment it lived in, and how unpreserved anatomies (muscles, skin) can be rationalized from fossil data. Equally important are the skills of a natural history artist, such as being able to produce realistic scenes of the natural world, to arrange interesting compositions, and predict how light and shadow would play out on alien, ancient forms (Fig. 1.3). A growing body of books, websites and exhibitions showcase palaeoart, but the process behind these reconstructions remains largely confined to relatively obscure or specialist publication venues, often written in technical language that challenges lay audiences.

This book attempts to outline this process in a detailed but understandable manner. This is not a ‘how to draw dinosaurs’ guide where prehistoric animals are broken down into geometric shapes for easy illustration, but a discourse on how artists and researchers can read fossil remains to obtain scientifically credible understanding of their life appearance and behaviour, and translate these into attractive, informative artworks. We will cover the goals and limitations of palaeoart, the history of the discipline, the methods employed to reconstruct the ancient tissues and life appearances of long-dead animals, look at conventions of depicting these creatures in restored ancient landscapes, and finally outline aspects of working in the palaeoart industry today. Because producing an artwork is only part of the palaeoart process, it is hoped that this content will also be of interest to those who commission and advise on palaeoart: consultants, exhibition designers and other palaeoart patrons have their own ‘best practices’ too.

Objectives and aims of palaeoartistry

The drive to produce palaeoart seems to act at a fairly primal, subconscious level. Much like some of us feel a need to capture landscapes and fauna in natural history art, looking at fossils makes some of us want to rationalize and predict the likely life appearance of these long extinct creatures. The exact cause behind drives is probably unimportant: it may be enough to admit that nature is fascinating and beautiful, that we enjoy expressing our admiration of it in art, and that art helps us communicate our ideas and interpretations of the world with others. It is important, however, to discuss exactly what we can hope to achieve in palaeoart, what its main applications are, and where its limitations lie.

Defining a genre of art is never easy, but it’s clear that not all artwork involving fossils can be considered palaeoartworks. We might broadly diagnose palaeoart as requiring three essential elements: 1) being beholden to scientific data; 2) involving a restorative component to fill in missing yet essential biological data; and, of course, 3) relating to extinct subject matter such as ancient landscapes, animals and plants. We can thus rule out technical illustrations of fossil specimens as palaeoart, as they might depict components of fossil organisms, and they might be scientifically-informed, but they lack a restorative element. A skeletal restoration or mounted skeleton of a fossil creature might be classed as palaeoart however, as they involve reconstructing damaged or missing bones, inferring posture and sometimes predicting a soft tissue outline. They do not, of course, attempt to show living animals as we would see them in life, and some may argue that prevents them being ‘true’ palaeoart. Whether they are classifiable as palaeoart or not, they are clearly a related art form and their production is an important step in the palaeoartistic process.

Fig. 1.4 Not all reconstructions of fossil animals are equally ‘accurate’ or credible: the availability of fossil data and our depth of research determines how restorable different species are.

Palaeoartistry is not science, but science-informed art. There is a large scientific component to palaeoart production, but the overwhelming majority of fossil animals cannot be restored without extrapolation, prediction and – more often than we like to admit – some degree of speculation (Fig. 1.4). It is important that we remain as evidence-led as possible however, and one of the most critical goals of palaeoart is accurately portraying elements of ancient subjects which we can be sure of: aspects like animal size, their basic proportions, known (or reliably inferred) aspects of their soft tissue anatomy, their contemporary fauna, flora and habitats, and so on. When data runs dry, we do not take the approach of ‘anything goes’: we must use reasoned extrapolation and informed speculation to plug the gaps necessary to bring our work to completion. The moment we start taking an ‘anything goes’ attitude to recreating fossil life, it ceases to be palaeoart, and it becomes palaeontologically-inspired art.

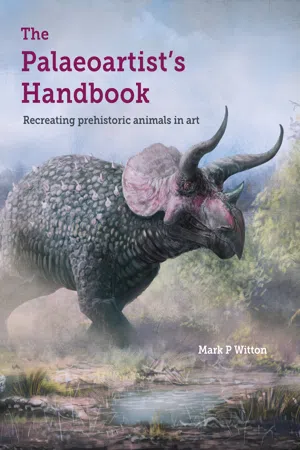

Fig. 1.5 Triceratops horridus, restored as understood in 2017. Giant scales, a face covered in a thick cornified sheath and whirling horns are not typically depicted on this species, but are suggested by contemporary data and interpretations. As science moves on, so does palaeoart. (M. Witton)

We should ask ourselves what, specifically, are we restoring in palaeoart: the actual ‘truth’ of ancient worlds, or hypotheses about the life appearance and palaeobiology of our subject species? Generally speaking, palaeoartistry is seen to pursue ‘accurate’ renditions of ancient species, seeking one ‘true’ visage of an ancient species. Our artwork is judged against its conformity to scientific thought, and described as ‘accurate’ or ‘inaccurate’ based on its adherence to contemporary palaeontological hypotheses. But is ‘accuracy’ what we’re really after in palaeoartistry? In reality, what is considered ‘accurate’ is in a constant state of flux within palaeontological science (Fig. 1.5). As evidenced by palaeoartworks themselves, we have sometimes dramatically altered our perceptions of the appearances and lifestyles of ancient organisms. Moreover, science is not a linear process where a single concept always takes pole position as the ‘most accurate’ interpretation of a given issue. Scientific progress is messy and nonlinear, with our knowledge of a given topic branching, reversing, ceasing, reviving, and revising as it goes along. A united consensus on what is ‘accurate’ will exist on some topics, while opinion may be divided over a few hypotheses on other subjects, or else a field may be poorly understood and open to many interpretations. The idea that palaeoart can always reflect a single, truly ‘accurate’ idea is naïve to the scientific process, and implies that our reconstructions can be thoroughly tested against fossil data. This is also false because so much of the data required to comprehensively reconstruct fossil subjects are now lost to time.

Palaeoartistry may be thus be better described as the process of illustrating credible contemporary interpretations of prehistoric animals, where testable aspects accord with fossil data and non-testable aspects are based on well-researched inference. Our primary goal and guiding thought should be the creation of defensible and likely interpretations of ancient life, and we should not pretend that we are able to portray definitive versions of fossil animals. Because our data are always improving, science is always shifting the goalposts of what is probable and most of our artworks will be superseded in time. Our work records the history of palaeontological thinking, synthesizing opinions on the anatomy, lifestyles and habitat preferences of ancient animals that were contemporary to our generation of palaeontological science. But palaeoartists are not beholden to scientists for improving our understanding of ancient life. Through careful study of fossils and anatomy, artists can also move us closer to depicting genuine realities of ancient life, as has been demonstrated by several researching palaeoartists in the last two centuries.

This view is not meant to be pessimistic or disparaging, however. Our ability to interpret life appearance is always improving and an increasingly science-led approach to palaeoart means we are following the right paths to ever more credible restorations, even if there is still some way to go. If we need encouragement, the history of palaeoart is a fantastic record of how far we have already come.

Applications of palaeoart

Palaeoartworks feature in a variety ...