![]()

1

EFFECTIVE AND ENGAGING COMMUNICATION

Communication comes naturally to human beings. From the moment a baby draws its first breath and lets out that cry, it is communicating, and will continue to communicate at varying levels of effectiveness throughout the course of its life. It is no wonder then that communication is often cited as the most important life skill a person can possess. It is our means of acquiring knowledge, of progressing, of asking for help and, on an extreme level, our survival may depend on it.

In the vast majority of job adverts, ‘excellent communication skills’ are listed as an essential requirement. Employers know that those who are good at expressing themselves in an articulate way have a far greater chance of succeeding in the workplace. It goes without saying that the ability to communicate well is at the top of every aspiring presenter’s tick list, because it is pivotal to their purpose. Presenters who are unable to communicate are as effective as doctors who are scared at the sight of blood. It is therefore helpful to understand the different elements that are at work when people communicate with each other.

WHAT IS COMMUNICATION?

The word ‘communicate’ comes from the Latin communicare, which means ‘to share’. In its simplest form, the process of communication consists of three main elements:

1. The sender who generates and imparts a message.

2. The channel through which the information is conveyed.

3. The recipient receiving the message and decoding it.

The sender generates a message that is sent via the channel (words, tonality and visual signals), to be interpreted by the receiver.

The TV or video presenter is in the position of sender, as they are generating the message to send. The channel through which they are imparting their message is their speech and/or expressions. The recipient is the viewer. The channel should be a presenter’s main concern and a full, in-depth understanding of how it works is a distinct advantage for a communicator.

THREE-DIMENSIONAL COMMUNICATION

When formulating words, sentences and questions, the sender’s main focus is on the message they want to convey. For example, when they say, ‘Would you like to go out for dinner with me?’, in their mind, they are thinking about their desire or need. The words, expressions, tone of voice and movements that convey that need are formed largely on a subconscious level. The recipient hears the words, but is also aware of the tone of voice in which the message is being imparted, and is watching the way the sender looks as they say it. They use all three factors to ascertain the meaning or intent of the invitation. Is the ‘dinner’ just an opportunity to eat and discuss work, or is the offer something more complex, multi-layered and potentially romantic?

The true meaning of the message – the intention, sentiment and feeling – is carried mainly in subtle tonal and visual signals.

If the sender has no real meaning, or is just trying to remember a script and get the words out in the right order, the tonal and visual signals will conflict with the words being said.

Only by taking into account all three dimensions – words, tone of voice and visual signals – can the recipient properly interpret the sender’s true intention. A presenter is in the position of sender, but very often they have interrupted the natural process of formulating messages, by removing any need or desire and consciously preparing the words they are going to say. It is no wonder, then, that first-time presenters can feel awkward and nervous. If the normal desire or need to communicate a message has been replaced by consciously scripted words and an unnatural feeling, this is what will be formulated on a subconscious level and this is what the recipient will receive.

Part of the job of a presenter is to make it as easy as possible for the viewer or listener to understand the message. Sending awkward, unnatural signals gets in the way of that process, so it is vital to eliminate any of those and master the art of formulating consciously prepared messages and scripts. To do that requires an understanding of the concept of three-dimensional communication.

PARALINGUISTICS

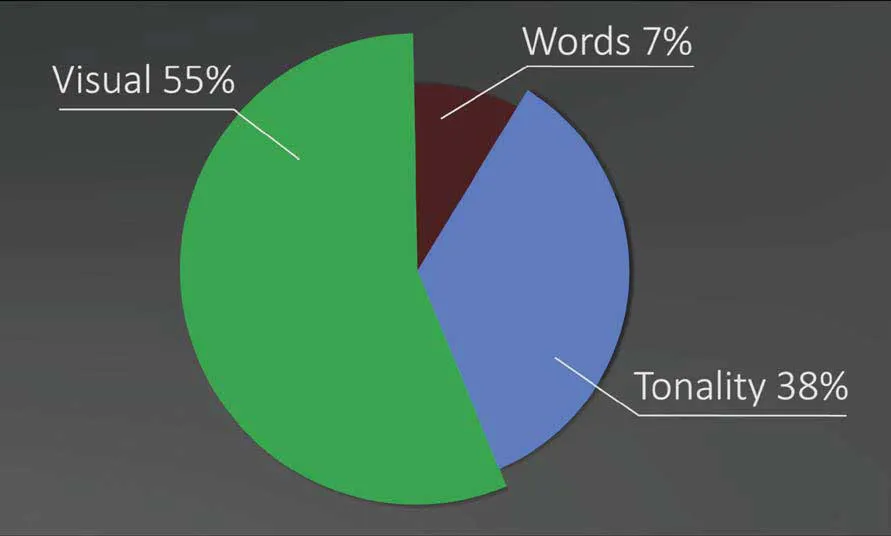

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Professor of Psychology Albert Mehrabian, from the University of California, conducted a number of studies into the ways in which different forms of communication imparted by the sender are interpreted by the receiver. One of these studies dealt with paralinguistics, which is defined in the Oxford Dictionary as ‘communication through ways other than words, for example tone of voice, expressions on the face and actions’. From his findings, Mehrabian formulated what has become known as the 7-38-55 Rule. This states that only 7 per cent of the underlying meaning, the feel or intent of what we communicate occurs by way of the words, while 38 per cent comes through tone of voice, or tonality as it is known, and 55 per cent through visual signals such as facial expressions and body language.

The true or underlying meaning of what is being said is carried in facial expressions, body language and tonality.

The way in which Mehrabian conducted his research has been the subject of much criticism over the years. However, the concepts offer some useful insights into and understanding of the importance that presenters should place on the different aspects on non-verbal communication.

Words (7 Per Cent)

If you are new to presenting, chances are you are going to find yourself overly focusing on the words you choose to say. You might worry that you will miss out words, forget the lines or lose your place. You might worry that your tongue will freeze, and you will not be able to get the words out, or that you will be judged for what you say.

These are all very natural worries that tie in with ten greatest fears public speakers have:

• Fear of being judged.

• Fear of coming across as stupid.

• Fear of being ‘found out’, aka imposter syndrome.

• Fear of making a mistake.

• Fear of forgetting what to say.

• Fear of freezing or becoming-tongue tied.

• Fear of saying something politically incorrect.

What is interesting about the words, however, is that they prove effective only if they are in alignment with the way you say them, and the way you ‘come across’ as you say them. If you do not believe the words you are saying, or you are unsure of yourself or unclear about what they mean, you will not be able to deliver the words in a convincing way, as your unconscious communication, tone of voice, facial expressions and body language will let you down. The viewer will become preoccupied by what you are not saying as opposed to by the words coming out through your lips. It is for this reason that being comfortable and well-practised with the words and messages makes all the difference to how you come across when you present.

Tonality (38 Per Cent)

Everyone has had the experience of sitting through a talk, class, lesson or speech, where they are a captive audience for a speaker droning on (and on), to the extent that all they can do is keep their eyes on the clock and will the time to speed up. The main reason for this sense of tedium is generally a lack of any variation in the tonality of the speaker’s voice.

Tonality is the way you sound when you speak and is determined by your volume, pitch, pace and rhythm. Making adjustments to any of these individual aspects of tonality can completely change the meaning of the words. Take the simple sentence, ’It is really great to be here.’ First, try saying the sentence with an upbeat pace, mid-to-high tone and a good variety of pitch, placing strong emphasis on the ‘really’ and the ‘great’. Second, try the same phrase but with a low pitch, in a monotone and slow.

The first example is more likely to sound as though it is genuinely meant and that it is actually really great to be there. The second may well be interpreted as sarcastic, bored or cynical, changing the feeling and therefore the meaning of the message.

Your tone of voice can help the viewer ascertain whether you are being serious or fun, teasing or genuine, worked up or calm. People who are new to presenting often lack the confidence to ‘play’ with their voice and see what they can do with it to create maximum impact. At first, they will tend to keep the voice within a narrow tonal range as this will be their comfort zone, where they feel safest. The problem with keeping the tone of your voice at one level is that it runs the risk of sounding monotonal.

The very word, ‘monotonal’, implies the flat mood it creates. When the range of tone is limited to just one level, the audience will perceive the presentation as repetitive and so tend to switch off and stop listening. Nine times out of ten, a speaker who has the ability to engage with an audience will be doing so not only because of the words they say but also because of the way they are expressing them. They wil...