![]()

A stylish dolls’ house designed by Holly Beck, based on one of the famous Circus houses in Bath. Available from Dolls House Miniatures of Bath. PHOTO: HOLLY BECK

1 INTRODUCTION

‘When we mean to build,

We first survey the plot, then draw the model;

And when we see the figure of the house,

Then we must rate the cost of the erection;

Which if we find outweighs ability,

What do we then but draw anew the model …’

Lord Bardolph in Henry IV, Part 2 (1597) Act 1, scene 3, by William Shakespeare

There is magic in a scale model, and the more detailed, the more accurate, the more true-to-life the model, the greater the magic it contains. We recognize this magic as children when we play with our dolls’ houses or toy trains. A child’s world has strict limitations, and it is hard to appreciate the concept of ‘house’ or ‘train’ when one’s world is too small to encompass the object as a whole. However, through a model, children can explore the world about them without the intimidation of being considerably smaller in size than the adults the world is designed for.

For those of us who became fascinated by the theatre at an early age, a toy stage will always hold a very special magic: it allows us to experiment with exciting but impractical theatrical notions that we know could never become reality in a full scale production, but when combined with the creative imagination of a child, those miniature shows hold an enchantment of a kind rarely found in the real world. Limitations of mere size are far easier to cope with than the restrictions imposed upon us by considerations of budgets, safety, time, and the multitude of technicalities we have to take into account as set designers, and we can also ignore those stylistic restrictions we must impose upon ourselves in our grown-up, real-life design work. In our toy theatres, our imagination is given free range.

Ancient civilizations appreciated the magic contained in miniatures, as the beautiful models excavated from tombs clearly demonstrate. Egyptian tombs held scale-model boats, chariots and miniature rooms, elaborately furnished for use in the after-life, and the tombs of Chinese potentates have contained whole armies in miniature. The fact that these objects are far too small to be of any practical use to their owners is ignored, and the scaled-down objects are seen as an adequate substitute for reality.

The elegant entrance hall of the Bath Circus dolls’ house. PHOTO: HOLLY BECK

The scale models we build as set designers are, of course, quite different in purpose, but also contain a certain element of magic, for they constitute a prediction of the future, demonstrating a wish or desire for some future creation. Sometimes the creation turns out to be glorious, and sometimes (less often, we hope) it is doomed to failure. However, like all theatrical productions, once the creative act is complete, it has served its purpose and becomes redundant: hence the sad, dusty and battered models sometimes found quietly mouldering on the topmost shelves in theatre workshops, but still containing, under the dust, the shadowy record of a creative act.

In fact, the theatre is in itself a model of a kind, for the performances that take place upon its stage are not reality, but, however far removed, constitute a representation of some aspects of life itself: it is a model for Life. Many believe there are yet deeper layers in the model, that the world we inhabit is merely a model of some divine or cosmic after-life; or even, as Douglas Adams demonstrated in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, merely a huge model built by mice to work out the answer to the Meaning of Life, the Universe and Everything.

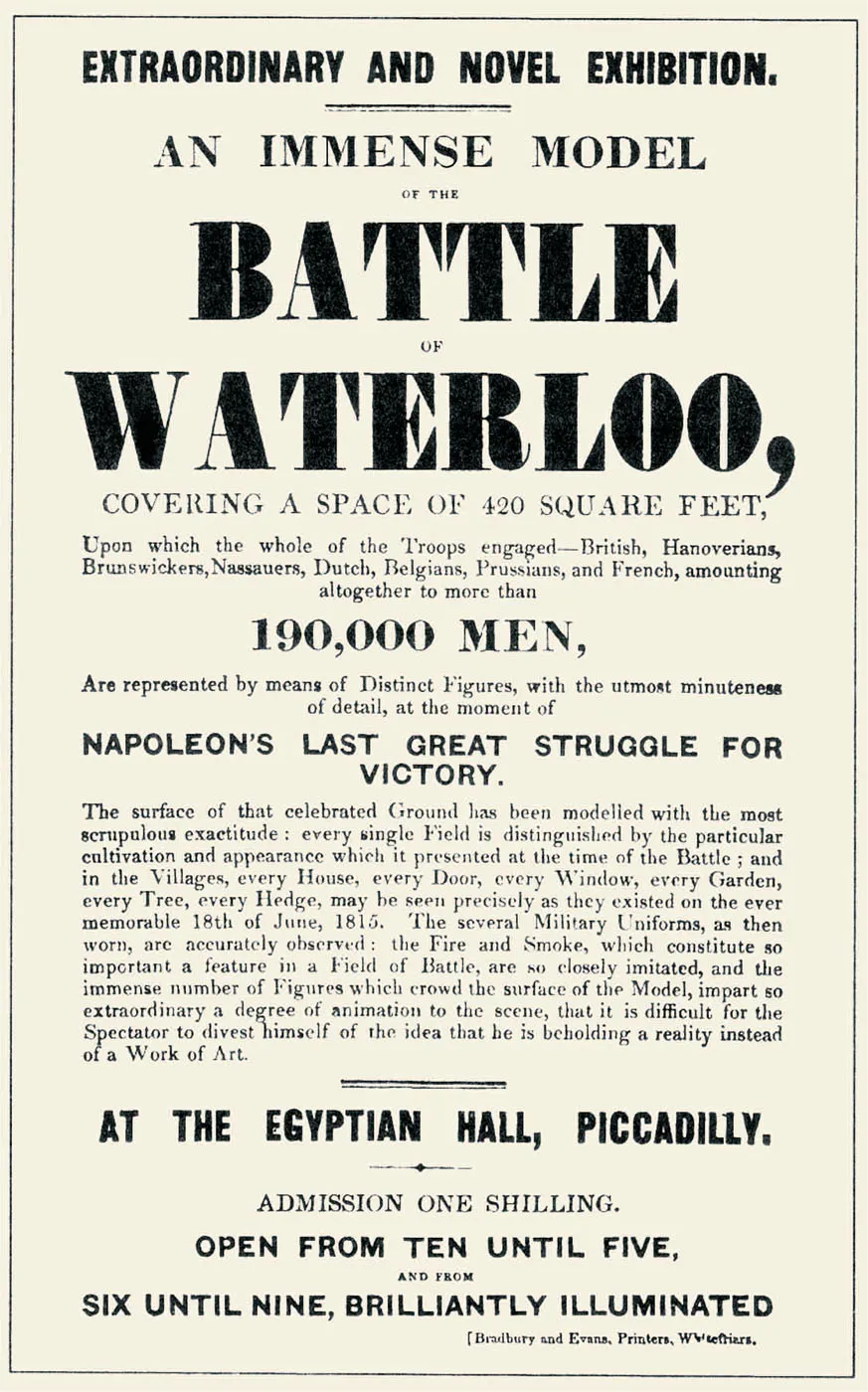

Occasionally, scale models attain a remarkable degree of notoriety: whenever an architect’s model for a new building is exhibited there is frequently a cry of public outrage against the proposed design. In the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral we can still see the ‘Great Model’ that Wren had constructed to demonstrate his concept for the new cathedral – but Sir Christopher Wren’s beautiful model was considered deeply shocking at the time, and he had to resort to a degree of subterfuge to persuade the Church hierarchy of his day to accept his controversial design; and in the National Army Museum in Chelsea, visitors today can still admire a vast model of the Battle of Waterloo covering over 37sq m (about 400sq ft) and including 75,000 finely modelled and painted tin soldiers – but at the time it so offended the Duke of Wellington, because it demonstrated that he had not, in fact, won the battle single-handedly as he had claimed, that it had to be severely altered to appease the irate Duke. Its builder, Captain William Siborne (1797–1849), having devoted years of work to researching and constructing the model, eventually died an impoverished and broken man. A model, it seems, can also contain the power to corrupt.

Details of the impressive model railway layout of the Edmonton Model Railway Association in Alberta, Canada. PHOTO: J. VAN ENS

The Neptune, a hand-painted Victorian toy theatre from Benjamin Pollock, still holds a special charm, in spite of its disregard for technicalities such as scale and sightlines that concern the set designer today.

Sir Christopher Wren’s ‘Great Model’ for St Paul’s Cathedral was built from oak in 1673–74, at a scale of 1:24. It is 6m (about 20ft) long, high enough for a man to stand up inside, and cost as much as an average London house of its day. It was constructed with superb joinery and exquisitely worked cherubs’ heads, flowers and festoons. Originally some of the detail was gilded, and the parapets were surmounted with tiny statues, which were probably Wren’s first commission to Grinling Gibbons, the master craftsman who produced much of the fine carving to be seen in the building today.

PHOTO BY KIND PERMISSION OF THE DEAN AND CHAPTER, ST PAUL’S CATHEDRAL

A set model, however, does not usually corrupt anyone, although it may occasionally shock, for despite its inherent charm, it is a model with a practical purpose. It is not a toy, and unless it eventually ends up in some kind of retrospective exhibition, it will be seen by only a very small group of people. In fact it has several purposes, in that a large part of a designer’s work consists in communicating creative concepts to the team of people working on the show in production. The director, actors, stage management, set builders, property departments, costume and lighting designers need to be familiarized with the set designer’s intentions long before they become concrete reality, and sheets of technical drawings, which need some skill to interpret, can never hold all the information the designer has to communicate to all these various departments, however detailed they may be.

This is where the scale model becomes preeminent. A glance at the model will show precisely what the designer has in mind, including many important aspects that cannot be indicated in the drawings, such as colour and texture. Anyone looking at the model will appreciate those aspects that affect his or her particular interest: the actor will note any steps or levels that he will have to negotiate in performance; the builder will notice any parts that might be tricky to construct or support; the costume designer will register the colours that the costumes will need to interact with on stage; and the lighting designer will note implied light sources and those places that might be difficult to light. Some directors like to use the model to plan their entire production in advance; others prefer to work more spontaneously, but will nonetheless use the model to keep a clear image of the set in their mind during the rehearsal process. The scale model is therefore an invaluable tool for all these people, and is generally considered indispensable to any production.

The lines quoted at the head of this chapter seem to indicate that Shakespeare appreciated the value of a model, although Lord Bardolph is not talking about the type of model discussed here – and in fact Shakespeare had no need of set models, because the Elizabethan playhouses provided him with an acting space which, through the power of language and his audiences’ imagination, was perfectly adequate for any production in the players’ repertoire. The more elegant and sophisticated performances at Court or in the banqueting halls of ducal palaces, however, presented some problems. Here, performances were required to take place in rooms with distinguishing architectural features such as fireplaces, doors and windows, and containing an assortment of domestic furnishings, and it would have been difficult for an audience to visualize, say, a wood near Athens or a stormy sea while looking at oakpanelled walls hung with family portraits.

Captain Siborne’s huge model of the Battle of Waterloo created a sensation when exhibited at the Egyptian Hall in 1838, but the Duke of Wellington objected to the inclusion of a large number of Prussian soldiers because it gave the (quite correct) impression that he had received a great deal of assistance from that quarter. Pressure was brought to bear upon the unfortunate Captain Siborne, and he was obliged to remove thousands of exquisitely detailed, 1cm (about ½in) high Prussian soldiers to preserve the Iron Duke’s reputation of being solely responsible for the great victory.

Design by the architect and scene designer John Webb (1611–72) for Sir William Davenant’s opera The Siege of Rhodes in 1661.

PHOTO: THE SANDRA FAYE GUBERMAN LIBRARY

The solution was to command the Court architects and painters to design spaces especially for performance. Many of the royal palaces of Europe contained extremely spectacular theatres, and travellers described the elaborate scenic effects they had seen on their journeys. Elizabeth I had been comparatively economical in her entertainments at court, but her successor James I – or more particularly, his queen, Anne of Denmark – was prepared to expend huge amounts of money on ever more spectacular productions. The celebrated English architect and designer Inigo Jones (1573–1652) found that one of his principal functions at court was to design stages, machinery, scenery and costumes for elaborate masques of a kind that were never encountered in the popular theatres on the south bank of the Thames, nor even in the private theatres of Blackfriars or Whitefriars.

Inigo Jones greatly admired the skilful use of perspective that he had seen in Italy, and he introduced many of these effects into his work at the court of King James with spectacular success. However, the court painters used the tools and techniques with which they were already familiar to produce their scenes; and their scenery, painted on large canvas-covered wooden frames that were bigger versions of the kind they used for portraiture, was seen literally as a mere background to the action, and there was little or no interaction between the performers and the scenery behind them. Even the machines designed to lower gods from painted clouds or t...