![]()

Chapter One

The Art of Speechwriting

Of all the talents bestowed upon men, none is so precious as the gift of oratory, [anyone] who enjoys it wields a power more durable than that of the great king.

Winston Churchill

[Rhetoric is one of the] greatest dangers of modern civilisation.

Stan Baldwin

Rhetoric is … older than the church, older than Roman law, older than all Latin literature, it descends from the age of the Greek Sophists. Like the Church and the law it survived the fall of the empire, rides into the renascentia and the Reformation like waves, and penetrates far into the eighteenth century; through all these ages, not the tyrant, but the darling of humanity; soavissima, as Dante says, ‘the sweetest of all the other sciences’.

C.S. Lewis, English Literature in the Sixteenth Centuryi

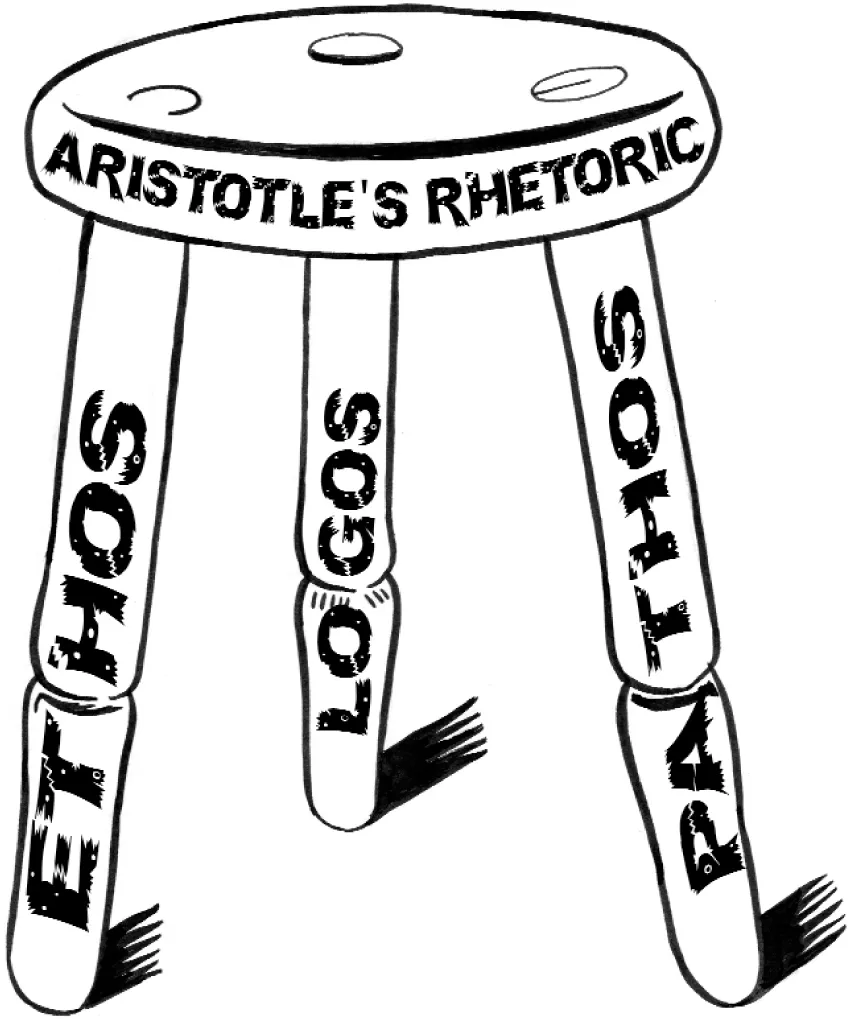

Aristotle’s Golden Triangle of Speechwriting

In 350 BC, Aristotle produced The Art of Rhetoric. It was the first definitive account of the art of speechwriting. Over the centuries, it has been subjected to intense scrutiny from some of the greatest minds in history but emerged unscathed, surviving profound technological, political and social change. As Thomas Babington Macaulay wrote in a nineteenth-century essay about rhetoric, ‘both in analysis and in combination, that great man was without a rival’ii. The Art of Rhetoric comprises three lectures spread out across three books. It was not a work of invention or deduction but observation, meaning that Aristotle did not make up the techniques himself but sat around the tavernas and temples of Ancient Greece studying the techniques of the ‘naturally eloquent’iii and noticing what worked and what didn’t. Judging by the depravity of techniques he suggests, he must have come across a right motley crew of Del Boys: some of the techniques in The Art of Rhetoric would make Alastair Campbell’s eyes water. It remains the ultimate guide to the art of spin.

Aristotle boiled persuasive speaking down to three essential ingredients: ethos (meaning the character and credibility of the speaker, not in its more widely understood modern meaning of ‘the spirit of an organization’), pathos (meaning the emotions of the audience and the emotions of the argument – not, again, in its more widely understood modern meaning of ‘suffering’) and logos (meaning the proof, or apparent proof – Aristotle himself was careful to draw this distinction). Aristotle argued that each of these three elements were not only equally crucial components in any act of persuasive speaking, they were all also mutually supportive. For instance, a speaker would be more likely to sweep his audience along with an emotional appeal if he had previously established his credibility and constructed a robust argument.

We will keep coming back to Aristotle’s golden triangle throughout this book. It remains the cornerstone for any speechwriter. But this chapter also sets out three further golden triangles of speechwriting: the three golden principles, the three golden rhetorical techniques and also the three blackest lies about speechwriting.

The Three Golden Principles of Speechwriting

The first golden principle of speechwriting is that the audience is more important than the speaker. By this, I mean that the true measure of the success of a speech is not how smug and self-satisfied the speaker feels as he leans back into the lush, leather seats of his chauffer-driven car roaring away from the venue, but what the audience is saying as they gather around for that awkward coffee and soggy biscuit back in the conference hall. Most of us will, at some time or other, have experienced that excruciating moment when a fellow delegate asks what we thought of someone’s speech and we realize we can’t remember a damn thing about it – even though we watched it just minutes before.

Audience focus is crucial for a great speech and always has been. Aristotle opens The Art of Rhetoric arguing that: ‘of the three elements in speech-making – speaker, subject and person addressed – it is the last one, the hearer, that determines the speech’s end and object.’ Today, top US communications adviser, Frank Luntz, opens his book, Words that Work, with remarkably similar advice: ‘It’s not what you say – it’s what people hear. You can have the best message in the world, but the person on the receiving end will always understand it through the prism of his or her own emotions, preconceptions, prejudices and pre-existing beliefs.’iv In the past, there was a belief that you could plant an opinion into someone’s mind in the same way as a syringe pumps a drug into someone’s veins: the ‘hypodermic needle model’. Now, it is understood that any communication activity must begin with an understanding of why the audience is there and what they want: the ‘uses and gratifications model’.

Audience focus underpins modern communications theory, as well as the arts of hypnosis, propaganda and advertising. Hypnosis is based on the audience-led approach of ‘pacing and leading’.v Pacing is when the hypnotist aligns himself with his subject through empathy and mimicry, e.g. ‘You are sitting in your chair. You can hear the soft hum of traffic outside.’ The leading comes when the hypnotist starts implanting messages, e.g. ‘You know you can give up smoking.’ Advertising is also fundamentally audience led, driven by customer insights: for instance, the Ronseal ‘it does exactly what it says on the tin’ campaign was based on the insight that DIY customers wanted plain, simple instructions.

The audience must come first. A lack of audience focus has lain behind all of the cause célèbre speech disasters of recent years, perhaps the most famous of which was Tony Blair’s speech to the Women’s Institute in 2000. Blair’s fatal error was to try to lecture 5,000 fundamentally conservative people about the evils of conservatism.vi He said the word ‘new’ thirty-two times in his speech, always in a positive light, whilst the word ‘old’ appeared twenty-nine times, always in a pejorative sense. No wonder he was slow-handclapped and forced to finish his speech early. He had profoundly upset their values. It was like walking into someone’s house and putting your feet on the sofa. The blowback may have been fierce and furious but it was also utterly predictable.

A successful speech is one in which the speaker and audience are aligned: in appearance, if not in fact. A good speaker will not storm into a conference and aggressively impose and assert his views. This would be bound to fail. No one wants to feel hectored or harassed when they listen to a speech. Nor do we go to speeches to be told that what we know is wrong. Rather depressingly, the truth is that we go to speeches looking for information that reinforces our own views, confirming that we have been right along. The academic, Stuart Hall, says that people hail messages in the same way that they hail taxis. So audiences look out for particular messages which they like, take those and leave the rest behind. That’s why racist political parties trawl through speeches by the equality lobby; not because they wish to be converted, but because they are looking for evidence that proves ethnic minorities receive preferential treatment. So the successful speaker will not challenge the audience overtly but instead weaves their proposition in amongst the audience’s pre-existing ideas, almost leaving them with the impression that they came up with the idea themselves. This is not as hard as it sounds. It is actually just a matter of framing. We flash the audience’s views above the front door in blazing neon lights whilst surreptitiously smuggling in our speaker’s opinions through the back door. This is all an illusion but it is a necessary one. We do not seduce someone by telling them how wonderful we are. We seduce someone by telling them how wonderful they are. As John F. Kennedy might have said, ask not what your audience can do for the speaker, ask what the speaker can do for your audience.

The deeper we analyse our audience, the higher our ambitions can be for the speech. Some people may balk at these tactics – they do look sinister in black and white – but they are part and parcel of everyday human interactions. Just observe yourself the next time you are in conversation. We all constantly adapt the style and content of our speech to match the people we are addressing. We speak louder to older people; we use baby talk to toddlers. We refer back to things people have said to us before to encourage them to agree with us. Speechwriting is about translating those same processes to the podium. Anyone who considers themselves too righteous for such techniques might remember Michael Corleone’s immortal line from The Godfather: ‘We’re all part of the same hypocrisy, Senator.’

The second golden principle of speechwriting is that emotions are far more powerful than logic. This seems counter intuitive because it is so seriously counter cultural. From childhood, we are taught that reason must trump emotion (‘Stop crying!’ ‘Pull yourself together!’) When we start working, that conditioning becomes even stronger – we are encouraged to leave our emotions at the door along with our hat and coat. In speechwriting, however, we must flip this back completely. Emotion is the nuclear button of communication: guaranteed to cause an explosive response. The brain’s limbic system, which governs our emotions, is five times more powerful than the neo-cortex that controls our logical minds.vii And the emotional part of our brain is wired right through to the decision-making side. Every great speech in history has involved some form of emotional appeal.

There are many emotions we can appeal to: hopes or fears, anger or affection, pride or shame. The emotion we appeal to must be rooted in knowledge of our audience. Different audiences are predisposed to different emotions. You’re not going to garner pity from an audience that is predominately angry, nor will you find much optimism amongst a crowd that is feeling fearful. Emotional appeals cannot be made randomly. We should find out what the dominant emotion in the room is and play to that. We will usually know what it is either by instinct, intuition or insight. For instance, trade union audiences often seem to be angry, which is why they respond so well to speakers such as Nye Bevan, Arthur Scargill and John Prescott. Charitable audiences, on the other hand, tend to prefer appeals to pity. We must judge the emotional appeal carefully: if the speaker appeals to one emotion when another emotion is more prevalent, we could set our speaker on course for a catastrophic collision. This is what happened to Cherie Booth: she tried to play for pity when many people felt angry about her involvement with a convicted Australian fraudster. Likewise, George Galloway’s appeals to shame over Iraq alienated many people who disliked the war but were proud of ‘our boys’. Both suffered severe backlashes. So we should proceed with care when it comes to emotional appeals. Emotions are like a can of worms: once released, they are impossible to contain again.

Logic is actually an optional extra when it comes to speeches. Speeches move too fast. Logic doesn’t matter. As Macaulay said, we should not imagine that audiences, ‘pause at every line, reconsidering every argument … [when in fact they are] hurried from point to point too rapidly to detect the fallacies through which they were conducted; [with] no time to disentangle sophisms, or to notice slight inaccuracies of expression.’ The truth is that most speeches are stuffed to the brim with logical fallacies and no one even notices. By way of example, one of the most oft-repeated lines in ministerial speeches during the first ten years of New Labour was the (now forgotten) mantra that: ‘In 1997, we gave independence to the Bank of England. Since then, we have experienced the longest, uninterrupted period of growth in the nation’s history.’ This line sought to credit the government for the sustained economic growth using the ancient rhetorical device post hoc ergo propter hoc, meaning ‘after this, therefore because of this.’ This device misleads the listener into assuming a causal connection between two actually unconnected factors because they are placed next to one another. Interestingly, film directors use the same technique to suggest a narrative flow between scenes. It is, however, illusory and therefore useful for deceit.

Most logical fallacies sound deceptively reassuring. When Virgin Galactic’s president, Will Whitehorn, tried to extinguish safety concerns about Richard Branson’s first foray into commercial space flights, he said, ‘Virgin operates three airlines. Our name is a byword for safety.’ Whitehorn was making a general assertion (Virgin is safe) on the basis of a specific truth (that Virgin’s airlines are safe) in order to make an unproven suggestion (that Virgin Galactic will be safe). No connection can be drawn between the safety record of Virgin’s airlines and their future safety in the uncharted territory of space, but the fallacy provided a soothing sense of comfort and that was all that the audience required. Job done!

Again, those who feel a bit unco...