![]()

1 Historical Milestones

Cinematography, or the process of capturing the moving image, is a highly complex, creative and technical procedure that has been developed and refined since its beginnings. There are many specialist books about the history of film making, and cinematography in particular, which are required reading if you are interested in how the art and craft has developed. This book does not set out to cover the history in detail, but it is important to note some of the key moments in the timeline, especially those which will help you compare the rate of development during the first hundred years of its history (1888–1988) to those of the last twenty years.

THE EARLY YEARS

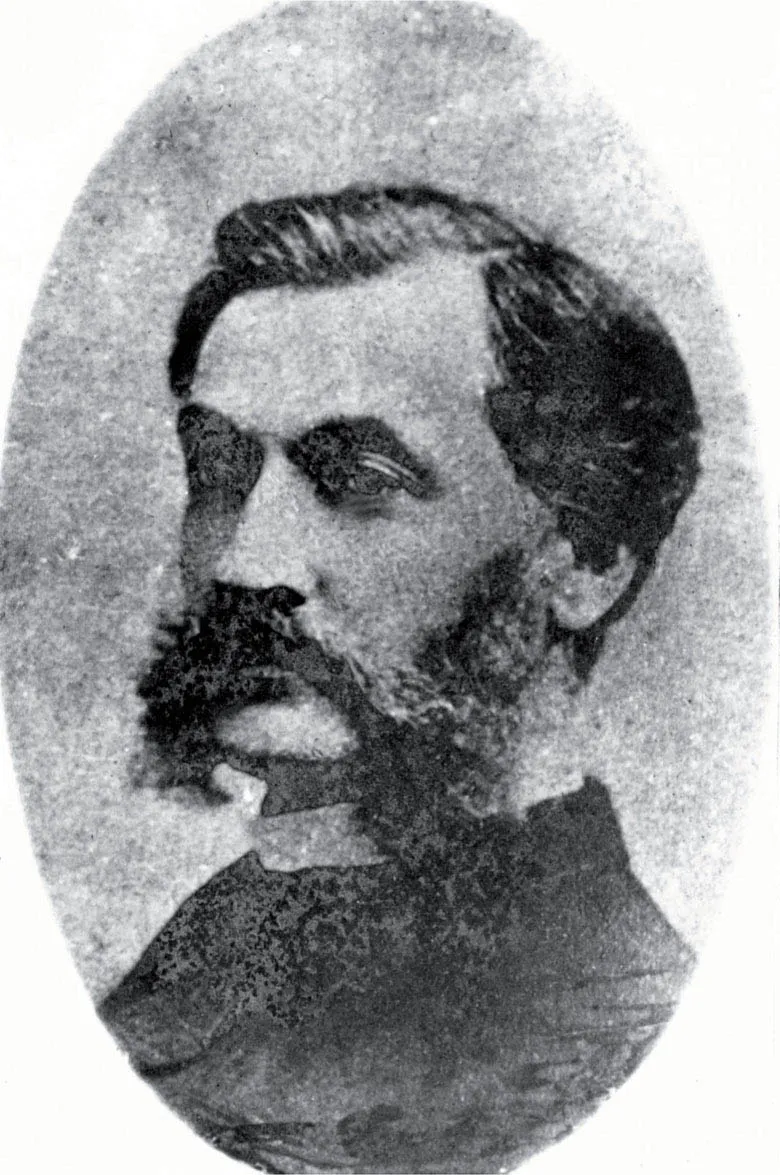

Once photographers had begun to master techniques for recording still images, they naturally wondered how they might record moving images. This started to happen in the 1880s when early pioneers such as Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904), Louis le Prince (1841–1890), Thomas Edison (1847–1931) and William Friese Greene (1855–1921) began to develop and patent their various techniques.

It would be wrong to credit any one of these people (or others) as the inventor of cinematography, as they all played their part in discovering methods of filming and recording moving images. However, it is interesting to note that there is an inscription on the monument to Friese Greene in Highgate Cemetery in London, which refers to him as ‘The Inventor of Kinematography’.

We can state quite confidently however that the Roundhay Garden Scene and Traffic Crossing Leeds Bridge, recorded by Louis le Prince, a Frenchman living in Leeds, are the oldest pieces of recorded motion picture material and date from 1888. Le Prince had built and patented a single-lens camera – a clumsy box-like device which recorded images on paper ‘film’ at between twelve and twenty frames per second. (Interestingly, 1888 was also the year that George Eastman registered the trademark Kodak.)

Of course these early experiments of Le Prince and others simply recorded, in black and white, events as they happened and with the camera being confined to only one position. Yet despite this lack of sophistication, or even a sound track, people flocked to makeshift cinemas to see the films which were being produced by these early pioneers. However, camera equipment, materials and techniques soon improved and the filmmakers were able to document these events more fully. This was to be the start of ‘documentary’ film making as we know it today.

Fig. 1 This is the memorial stone on the grave of William Friese Greene in Highgate cemetery in London. The wording claims he is the ‘inventor of kinematography’.

Fig. 2 Louis le Prince (1841–1890) recorded the first moving image in Leeds in October 1888. The Roundhay Garden Scene was shot at twelve frames per second and lasted for just over two seconds.

Fig. 3 Louis le Prince’s camera which recorded the images on paper ‘film’ 64mm wide. The upper lens is the viewfinder, the lower is the photographing lens.

SILENT MOVIES

Some film makers also started to experiment with fiction production, and so began the dawn of the golden era of the silent movies, with comedies being a special favourite with the audiences. These silent comedies as they famously came to be known, featured comedians such as Charlie Chaplin (1889–1977), Stan Laurel (1890–1965) and Oliver Hardy 1892–1957) and Buster Keaton (1895–1966). Although the films themselves were silent, more often than not their slapstick style of comedy was enhanced by a live piano accompaniment of mood music that would complement the story being told on the screen.

One of the pioneering film-makers actually went one step further with this mood music by introducing it whilst filming on location. Reflecting on some of his experiences, in an interview he gave to the BBC programme Yesterday’s Witness (1969), British teacher turned film-maker, George Pearson (1875–1973), told how he and his crew would, with great difficulty, take a piano on location in order to help the artists give a more ‘creative’ performance. In the grand tradition of film making, nothing got in their way, and even mountains did not stop them getting that piano there.

The desire of film makers to shoot works of fiction saw them also recording plays being performed in theatres. They would place their camera within the audience, simply pointing at the stage, and it would not move from that position throughout the performance. Their camera simply recorded the performance as though it were a member of the audience and as such was photographing it from a detached and impersonal point of view.

However film makers soon discovered that if they removed the audience, they could direct the performance themselves and importantly break the action into separate shots and sequences. By moving the camera from its fixed position in the auditorium and onto the stage itself, they could now photograph the action from the best possible angle and change the shot size so that they could move the audience’s point of view closer into or further away from the action taking place on the stage. We now had long shots, wide shots and close-ups. But the most important point was that the film makers were firmly in control and now had a director who could take control of what the audience was seeing.

What was developing was the technique that we now take for granted and call single camera production or simply film production, the definition of which is ‘making one camera look like it is doing the job of several cameras working simultaneously’.

Tip: Read about the Silents

Read Paul Merton’s book Silent Comedy, in which he traces and examines the evolution of the art of the silent comedy and the people both on and off screen who developed and mastered it.

THE TALKIES

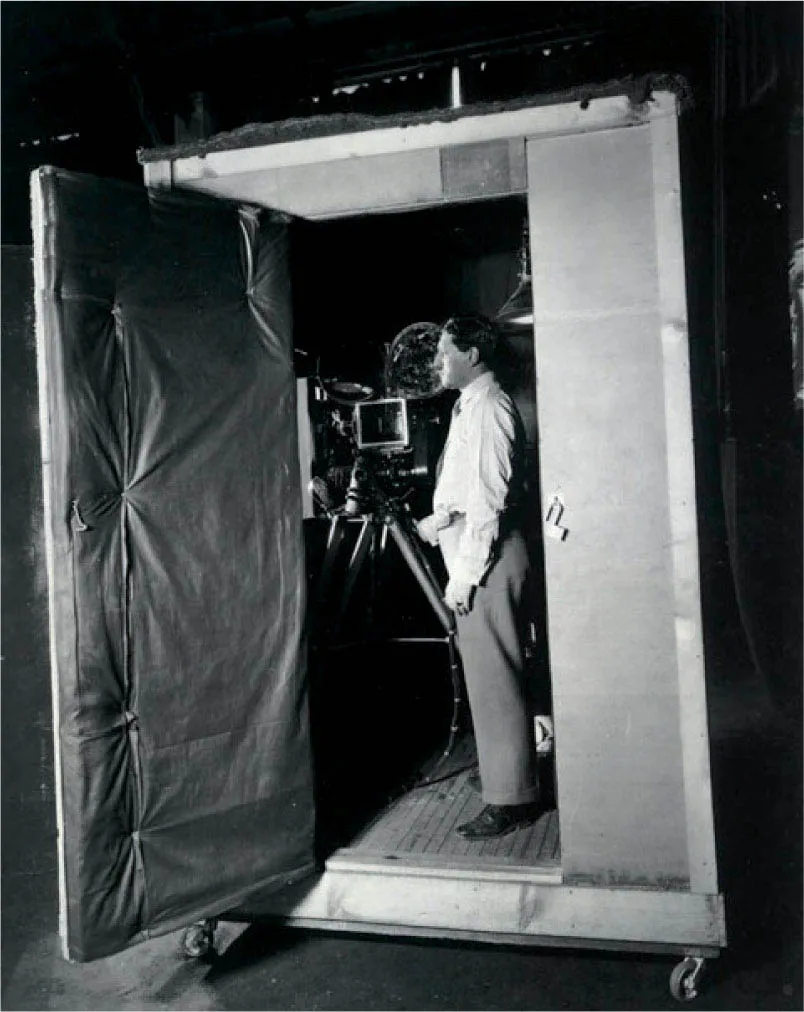

The 1920s saw the beginnings of the talkies, with early films shown with sound effects or music in the form of recordings, synchronized to the film. Later, the soundtrack was added optically to the film itself. Of course the recording of the sound track in the film studio or on location was a complex task which unfortunately posed new problems for the early cinematographers, in particular the sound equipment picking up the noise of the film travelling through the camera. The solution they came up with was to place the camera and the operator in a large soundproofed box, called a blimp.

Although this device solved the noise problem, by confining the camera to the inside of this box it greatly restricted the cinematographer’s choice of camera angle and also meant that the camera could not be mounted on a dolly so that it could be moved during a take. Because of these physical restrictions some cinematographers complained that the arrival of sound had put the art of cinematography back twenty years! But film-makers are an inventive bunch and before long a soundproof cover which the camera could be fitted into (also known as a blimp) was made and meant the camera could once again become mobile.

In 1928 the decision was made to shoot films at the rate of twenty-four frames per second, which is now the standard frame rate, although twenty-five frames per second is the standard rate in Europe for shooting film for television. This increase resulted in better quality sound and also reduced the flicker seen on films shot at the previous standard of sixteen frames per second. (Incidentally, this flicker also gave birth to the phrase ‘going to the flicks’.)

Fig. 4 In order for the microphones not to pick up the sound of the camera mechanism pulling the film through the camera, it and the operator were enclosed in this sound-proof booth often referred to as the ‘ice box’. The camera was unable to move whilst shooting.

Fig. 5 The camera could be taken out of the ‘ice box’ when a much smaller device called a camera blimp was invented. This now allowed the camera to be mounted on a tracking dolly in order to change shot size whilst filming.

THE COMING OF COLOUR

Until the 1920s cinematographers were using orthochromatic stock, which was sensitive only to blue and violet light, causing a range of colour problems. Artists appeared to have black lips, or their blue eyes were rendered as white, so makeup and filters on the camera had to be used to counteract these issues. This discrepancy continued whilst film manufacturers were developing an orthochromatic stock that was more sensitive to green and red light, which would record those colours a little more accurately. Eastman Kodak and other manufacturers had in fact been offering cinematographers a film stock which was sensitive to all wavelengths of the visible spectrum, but this panchromatic film stock was much more expensive than orthochromatic stock and was not used until the price was reduced.

Some black and white films had been colour tinted as a way of adding dramatic effect, but film manufacturers and cinematographers had been pursuing other ways of shooting and exhibiting films in colour. The first process which attempted to achieve this was the British Kinemacolor, invented by George Albert Smith (1864–1959) and developed commercially by Charles Urban from around 1909. In this system, black and white film was exposed in a special camera shooting at twice the normal frame rate, with each exposure being made alternately though a filter wheel containing a red filter and green filter. Unfortunately this process was not a great success, mainly because cinemas had to be equipped with special projectors that could reproduce the process. Even though these projectors were installed in around 300 cinemas across Britain, Kinemacolor finally fell out of use a few years later in 1914.

Another two-colour system similar to Kinemacolor was introduced by Technicolor in 1917, and by 1934 it had been developed further into what became known as the three-colour process. In this system, two strips of 35mm black and white negative film, one sensitive to blue light and the other to red light, ran together through one of the apertures in the camera. A third film strip of black and white negative film ran through a separate aperture, behind a green filter. Once the black and white negative images which represented the colours red, green and blue in the scene were processed, they were then used to produce a final colour print via a complex process using matrices and dyes. This colour system was used to photograph such films as Gone with the Wind (1935) and hundreds of others and Glorious Technicolor and Color by Technicolor were to be the measure for the hundreds of other colour systems that were developed, nearly all of which were judged inferior.

Christopher Challis BSC, in his book Are They Really So Awful? recalls that in 1937 he got a job with Technicolor on Wings of the Morning, the first colour feature film to be made in England, working alongside highly trained staff brought over from the United States. He spent five months locked in a darkroom, loading the magazines with the three separate black and white stocks that would be exposed simultaneously in the Technicolor camera. Every day a black and white rushes print was made from the previous day’s negatives before they were shipped back to the US for colour printing. This resulted in a gap of several weeks before the colour prints were returned. He tells the illuminating story of one occasion when no amount of pressure from the producers could achieve the return of a scene shot in Ireland. It later transpired that the Technicolor laboratory in the US was finding it next to impossible to get the post boxes red (in Ireland they happen to be green!). Having to expose three separate rolls of film through the camera meant it was heavy and cumbersome and, in addition, a lot of light was needed to make an exposure. The speed or sensitivity of the film was equivalent to an Exposure Index of 5 (EI5), while digital cameras of today operate with an EI of around 250.

What theatrical cinematographers were looking for was a ‘real’ colour film...