- 412 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Sport plays a crucially important role in our society and the benefits of participating in sport and physical activity are widely acknowledged in terms of personal health and well-being. Coaching makes a key contribution to sport, helps to promote social inclusion and participation, and assists athletes in achieving performance targets. Accordingly, this authoritative and comprehensive reference work will be widely welcomed. Written by acknowledged experts, it presents a detailed analysis of performance and good coaching practice and performance, and provides a concise overview of the coaching process from a scientific and pedagogical perspective.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sports Coaching by Anita Navin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Sport & Exercise Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1: PEDAGOGICAL ISSUES

IN SPORTS COACHING

1

Effective Coaching

Behaviour

by Anita Navin

The coach is significant in determining the success and overall impact of an athlete’s experiences in sport (Williams et al., 2003), yet the definition of effectiveness remains inconsistent amongst sport practitioners and organizations. The majority of sport coaches will measure their effectiveness in terms of the ‘value added’ to the performance of a team or an individual, and all coaches will try to encompass behaviours that promote success and personal development. Coaching is often referred to as a complex activity, and in order to be successful a coach must possess both the coaching process knowledge and sport-specific knowledge (Abraham and Collins, 1998). Effective coaching behaviour is often associated with positive outcomes for the performer – for example enjoyment, self-esteem and perceived ability. Bowes and Jones (2006) refer to coaching as ‘comprising endless dilemmas and decision making, requiring constant planning, observation, evaluation and reaction’ (p. 235), and this ability to identify, analyse and control variables that affect athlete performance is central to effective coaching (Cross and Ellice, 1997).

Early research into coach effectiveness suggested that the successful coach provided more feedback in practice; also indicated is the notion that this successful coach used more training and instruction behaviours than the less successful coach (Markland and Martinek, 1988). Research by Tharp and Gallimore (1976) involved the observation of John Wooden the legendary basketball coach from the University of California (UCLA), and used a category-coding system to identify the use and frequency of behaviours. Wooden had a proven ability to consistently produce winning teams, and it was his ability to communicate information, pass on knowledge, detect and correct errors in performance and reinforce behaviours, and his capability to motivate individuals, that received considerable attention when defining effectiveness. Observations of Wooden over fifteen practice sessions revealed that over 50 per cent of behaviours were categorized under verbal instruction, with other notable behaviours being hustles (12.7 per cent), praise (6.9 per cent) and scolds (6.6 per cent). Based on this early research, coach effectiveness was believed to encompass:

Figure 1.1 A coach engaging in the feedback process. (Courtesy of David Griffiths)

- Constructive feedback

- Prompts and praise

- Detection of errors and corrective measures employed

- High proportion of questions

- Numerous explanations and clarifying of a task and technique

- Vast proportions of a session engaged in instruction

- Management of the learning climate (Becker and Wrisberg, 2008).

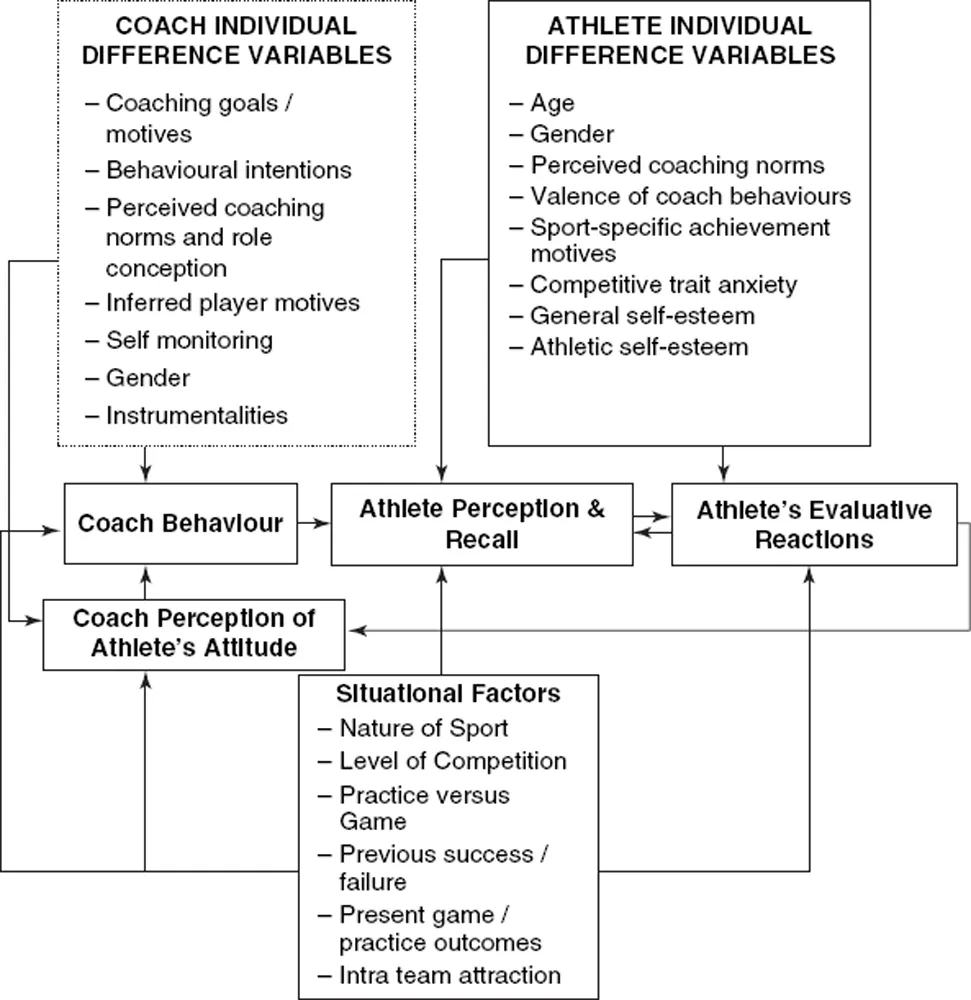

Smoll and Smith (1989) proposed a model of leadership behaviours in sport, which has been applied to the study of sport coaches and their effectiveness. Figure 1.2 outlines the model, which assumes the following:

- The coach behaves in a certain way

- The performer perceives and recalls the coach behaviours

- Based on this perception and recall, the performer has an evaluative reaction to the coach behaviours (see the solid arrow lines on the diagram)

- Situational factors along with the individual differences of the coach and performer determine the coach’s actual behaviour (see the broken arrow lines on the diagram) and the performer’s perception, recall and evaluation of the behaviour

- The effectiveness of the coach is therefore determined and dependent upon the dynamic interactions of all variables presented.

This model of leadership behaviour has been tested using the Coach Behaviour Assessment System (CBAS: Smith, Smoll and Hunt, 1977), which involves the observation of coach behaviour in competition and training. The observations were made using categories noted under either ‘Reactive Behaviours’ or ‘Spontaneous Behaviours’ (see box/panel on p. 16).

Figure 1.2 Model of leadership behaviours in sport. (Small & Smith, 1989)

While research studies using the CBAS have indicated that the use of instruction varies between coaches, it still appears as the highest scoring category. Lacy and Darst (1989) carried out some early research into coaching effectiveness and noted that skill-related instruction occurred three times more than any other behaviour. Claxton (1988) further confirmed this finding when reviewing the behaviours of tennis coaches. Age has been noted as a significant variable, and when a coach is delivering a session to young performers, Claxton (1988) noted a greater praise-to-scold ratio.

Gallimore and Tharp (2004) have since revisited some of the earlier research cited above, and while using the CBAS in the famous study of coach Wooden, other informal notes recorded during that study have since been made available. Other emerging behaviours of the coach identify the organization of practices and time on task to be important features of an effective session. Performers were often moving fluently between one practice to another, and transition time was kept to a minimum, ultimately maintaining the intensity of training within a session.

Categories of Coaching Behaviours

Class 1: Reactive Behaviours

Responses to Desirable Performances

Reactive Behaviours

- Reinforcement (a positive verbal or non-verbal reaction to good effort or performance)

- Non-reinforcement (no response to good effort or performance)

Responses to Mistakes

Mistake-contingent encouragement (encouragement given to the performer after a mistake)

- Mistake-contingent technical instruction (instruction or demonstration on how to correct a mistake)

- Punishment (a negative reaction, verbal or non-verbal, following a mistake)

- Punitive technical instruction (technical instruction that follows a mistake given in a hostile manner)

- Ignoring mistakes (no comments or action taken by the coach)

Responses to Misbehaviour

- Maintaining control (reactions to maintain order among the team or group)

Class 2: Spontaneous Behaviours

Game-related

Game-related

- General technical instruction (spontaneous, and not given following a mistake)

- General encouragement (spontaneous, and not given following a mistake)

- Organization (assigning duties, organizing space and groups)

Game Irrelevant

- General communication (interactions not related to the game) (Weinberg and Gould, 2007, p. 214)

The research study also noted the coach consistently modifying practice to ensure that skill execution became more automatic and fluent. Wooden did not believe that drill-like practices were the end, but promoted the notion that drilled practices opened up the opportunity for a performer to apply individual creativity and apply their own initiative. Emerging out of the early studies on coach Wooden was a perception that planning and detailed reflection of individual coach, performer and team performances led to a successful coaching programme.

Becker and Wrisberg (2008) outline the importance of feedback, and revealed that a performer is undoubtedly influenced by the feedback given by the coach. Higher levels of satisfaction are correlated to a high frequency of positive coaching behaviours, which include training and instruction, praise, encouragement, social support and democratic behaviour (Allen and Howe, 1998). Also noted is the notion than a performer’s perceptions of competence appear to correlate to the levels of praise and instruction received in response to a successful performance outcome. It is therefore assumed that the effective coach will ensure equity in levels of feedback to the individuals in a coaching session.

Becker and Wrisberg (2008) looked to extend the research findings linked to the CBAS observation tool, and carried out a research study that addressed the systematic coaching behaviours of Pat Summitt, a successful collegiate female coach (NCAA Division 1) in the United States of America. In this study another observation tool was utilized, namely the Arizona State University Observation Instrument (ASUOI: Lacy and Darst, 1984). This instrument contained thirteen behavioural categories representing three behaviours as outlined below:

- Instructional: pre-instruction, concurrent, post-instruction, questioning, manual manipulation, positive and negative modelling

- Non-instructional: hustle, praise, scold, management and other

- Dual codes: statements directed to an individual.

The findings of the study revealed that a significant amount of time was devoted once again to instruction, but the amount of questioning was also a significant finding when addressing the coach behaviours.

Coach Summitt’s Behaviours (per cent) after 504 Minutes of Observation

Instructional Behaviours

| Instruction | 48.12 per cent |

| Questioning | 4.61 per cent |

| Manual manipulation | 0.06 per cent |

| Positive modelling | 2.09 per cent |

| Negative modelling | 0.58 per cent |

Non-Instructional Behaviours

| Hustle | 10.65 per cent |

| Praise | 14.50 per cent |

| Scold | 6.86 per cent |

| Management | 9.34 per cent |

| Other | 3.19 per cent |

The study also compared the frequency of the categories directed to either the group or an individual. In contrast to pre- and concurrent instruction, the post instruction was directed mainly to individuals, with hustles, praise and management emerging as being directed mainly to the group. Findings in this study were consistent with the previous investigations, with instruction once again emerging as the highest score (48 per cent). Concurrent instruction appeared as the highest sub-total in this category, and highlighted how much support was being verbalized as players were carrying out a skill.

The study highlights that the expert coach will provide pre-instruction to the group, and post-instruction to the individual to promote greater benefits and confidence in the feedback process. The study also outlines that effective feedback should be brief and concise for an individual. Summitt also identifies the need for high levels of praise to motivate and promote perceptions of competence within a performer. Intensity of training was another feature emerging, and the expert coach is deemed to be someone who is able to replicate the game intensity in a training session, and ensure that all performers ‘practise like they compete’. It is the hustle behaviours that were used by Summitt to ensure that players remained on task and maintained the correct level of intensity.

The literature using the quantitative observation tools did convey some significant behaviours of a successful coach; however, limitations point to the need for future research to use qualitative data. Through gaining the perspectives of players, assistant coaches and the coach himself, the data obtained would have been enhanced.

The context a coach operates within is known to require different approaches and coach behaviours. Participation coaching will focus on the positive affective outcomes, including perceptions of competence and enjoyment, and may also be defined as being episodic, having loose membership and including transient participation. Smoll and Smith (2001) outlined the need to utilize the following behaviours when coaching a young performer:

- Use demonstrations frequently to support instruction and explanations

- Encourage and praise effort along with performance

- Provide feedback immediately after mistakes, and outline initially what was successful

- Remove any punishment strategies from the coaching session

- Provide positive reinforcement after any positive behaviour

- Ensure that expectations and codes of practice are clearly communicated.

In contrast, performance coaching has a higher level of commitment, fosters strong athlete-coach relationships, and will incorporate a significant planning regime for the mid- to long-term control of performance factors (Lyle, 2002). As a result of the complexity of the coaching process for a high performance coach, the literature offers some clarity in terms of coach effectiveness at this level. Gilbert and Trudel (2004) identified that several high-performance coaches were measured...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Contributor Profiles

- Part 1: Pedagogical issues in sport coaching

- Part 2: Applying sport science principles in coaching

- Part 3: Identifying and developing talent

- Part 4: Athlete support and management systems

- Part 5: Professional issues in coaching

- References