- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

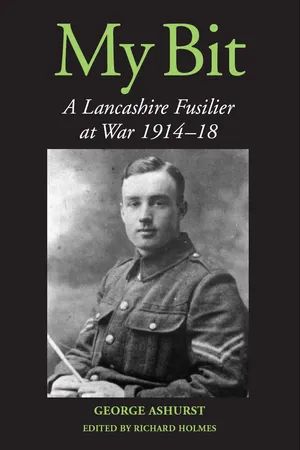

George Ashurst served with the Lancashire Fusiliers, taking part in First Ypres, Gallipoli and the Somme, and enduring months of trench warfare on the Western Front, making numerous grim and dangerous patrols into no man's land. His memoirs vividly reveal the reality of life in the trenches and the feelings of those who had to suffer it. Ashurst was often frightened and uncertain, occasionally infuriated by the 'shirking' amongst the officers, was usually ready for a cigarette or drink, but when his battalion attacked he would not shrink from his duty. My Bit is a fascinating and moving first-hand account of the First World War written by a working-class soldier.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access MY BIT by George Ashurst, Richard Holmes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World War I. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Lancashire Lad

I was born on 3 March 1895 in the village of Tontine, a pleasant little place between Manchester and Liverpool. There were about twenty cottages, a beer house and a little Methodist church in the village. When I came into this world my parents already had three children, two girls and one boy.

We lived in an old two-bedroomed house in the middle of a row of houses. We had no modern amenities such as gas, electricity, bathroom, or flush toilet. The kitchen had a stone floor which was mopped and sanded – no oilcloth, carpets, or rugs – and at night the house was lit with paraffin lamps. The furniture consisted of a heavy wooden table, a set of drawers, and three or four heavy wooden chairs. In the back kitchen, fastened to the wall, there were shelves on which the plates and cups and saucers rested when not in use, and two or three hooks were driven into the wall to hold pots and pans, etc. Of course there was no fancy paper on the walls, just a few coats of whiting.

In the kitchen there was a huge iron grate with a hob on one side that held the big iron kettle, and a boiler on the other side of the fire, which burned wood or coal. The grate was black and polished with blacklead, and hot water was always to be had from the boiler. On bath night for the children a zinc bath was brought into the kitchen from the outside, where it hung on a nail driven into the wall. It was partly filled with hot water in which the children sat very uncomfortably to bath.

At the back of the house there was a small garden, big enough to grow a few potatoes, lettuce, cabbages and rhubarb.

We were a poor family. My father worked at a stone quarry about a mile from the village, and his wages were rather poor. To make things worse, he kept half of his wages for himself and spent them at the village pub.

My mother took in other people’s washing to help pay the family budget, and was beaten every Saturday night by my drunken father for her trouble. She baked all our bread, kneading the flour and yeast in a huge ‘pan mug’, then placing it near the fire covered with a towel for the dough to rise. She baked the loaves of bread in tins, but specially for my father she had to bake ‘cobs’ on the oven bottom shelf. Of course during the week she would bake custard pies, apple pies and currant cakes, besides huge ‘barm cakes’ which the children loved, covered in black treacle or golden syrup, and oatmeal for breakfast covered in sugar or treacle. We used to beg for the top cut off father’s boiled egg.

Through my mother’s untiring efforts we were never short of food or clothing. As a young woman she had worked for years at a clothing factory and could always fix us up with cast-offs given to her by neighbours. Of course we didn’t have any pyjamas and slept in our little shirts on old iron beds on which were straw mattresses covered with cheap blankets and any old coats that were available to keep us warm in winter. As soon as I could walk about I had to wear a pair of clogs, but I had a pair of child’s slippers to wear on a Sunday to go to chapel with my elder brother and sisters.

Of course I don’t remember much of my baby days, but something that stands out in my memory quite plainly is what happened on Saturday nights when I stood with my brother and sisters in our shirts on top of the stairs, crying and listening to my drunken father beating my poor mother black and blue, and there was nothing we could do about it.

As I got older it came time for me to go to school. My brother and sisters took me on the first day to a very old school about a mile from home, called Hallgates School. I didn’t mind going to school at all except in the winter time, when it was foggy, snowing and cold. There were no school buses in those days, one slipped and trudged through the sludge.

It came my turn as I got older to take my father’s fresh-cooked breakfast to the quarry before I went to school, and also the breakfast of the man who lived next door. His wife was a very nice lady and always gave me a thick slice of bread which had been dipped in the bacon fat at the bottom of the Dutch oven in which she had cooked her husband’s eggs and bacon – a tasty bit I thoroughly enjoyed as I trotted off to the quarry.

Each Sunday morning I had to make a trip to the parish church of Upholland, not very far from the village, where I had to see the verger in the vestry and get two loaves of bread from him to take to a very old couple in my village.

Everyone in our little village knew every other person in the village, and I would say each other’s business too. Every door was always open to a neighbour, and if anyone required help it was quickly and generously given. The little pub with its cheap, good beer and its domino table was the main recreation and entertainment for most of the men, while the women and children enjoyed their evenings at the little Methodist chapel.

Of course there was no radio, television or cinema, and almost no newspapers. Very often on the winter nights neighbours got together in one house, gossiping, having a sing-song, or playing parlour games. They weren’t troubled about ruining posh furniture and carpets; there were none to spoil. They sat around on anything anywhere, eating sandwiches and drinking tea until it was time to retire to their own homes.

The country around the village in the summer time was beautiful and unspoiled by either people or machines. One could indulge in a long walk through the glorious fields, the silence broken only by the song of the birds or the gentle breeze through the magnificent trees. During school holidays I, along with other village boys, would set off early in the morning with a big bag of bread and jam sandwiches and a bottle of water – or, if lucky, a bottle of home made ginger beer made from nettles, dandelion, burdock, and meadowsweet. The whole day we would wander over the fields and into the woods, jumping ditches, climbing trees, chasing hares and pheasants, and bird-nesting, as happy and carefree as the day was long, trotting home at night tired out and as hungry as a pack of wolves. Then to bed, to sleep the sleep of an untroubled mind and a worn out body.

My father was a drunkard. He never went to church and was not concerned at all about religion. He never hit any of his children; my mother had to do the smacking when any of us was naughty. Still, he never objected to my mother and the children going to church so my mother saw to it that we learned about the Bible and Jesus Christ, and made us go to church twice on Sundays. Practically all our entertainment emanated from the little Methodist chapel, the children thoroughly enjoying the concerts and parties, especially at harvest time, when there was plenty of fruit on show, and at Christmas, when we received little presents and pretty cards.

In those days there was no flying off to the Continent or even going by train for a week at the seaside. In fact I only remember one occasion when I visited the seaside. The children were packed on to a wagonette drawn by one horse. It was a beautiful summer’s day, and we all carried huge packets of sandwiches, fruit and cakes, along with sweets and pop – our destination the sandhills at Southport. We laughed and sang as the old horse trotted along.

At one place on the journey the road went over an old bridge across the canal. We all had to get down off the wagonette to help the horse pull it up the steep gradient. On arrival at Southport it was our first sight of the sea, and we played about on the sands until we were exhausted. It was a glorious time and we all thoroughly enjoyed ourselves. Getting back on the wagonette for the return journey we were so happy, but very tired, and it was a long ride back. We sang the songs we had learned at the little chapel until the rhythmic clop-clop of the old horse’s shoes on the road lulled most of us to sleep long before we reached home.

On odd weekends my father would take me with him on a fishing trip to Abbey Lakes, a private estate not far from our village. To be allowed to get in the estate and fish my father had to pay twopence at the lodge gate. The grounds were beautiful with flowers and trees, and the lake in which we fished was thick with water lilies. In the middle of it was a pretty little island where lovely white swans nested, so that we had to be very careful with our fishing lines as they majestically swam by. There were no really big fish in the lake but we caught a few roach and perch. After a couple of hours we packed up our fishing gear and left the lovely estate, making our way home to dinner, which consisted of some chips and a fried perch.

Another incident that stuck in my childish memory was the day my grandma and grandad came to our house from Pimbo Lane, a village a couple of miles away from Tontine. My grandad was six feet tall; he had grey hair and a bushy grey moustache. He was wearing a black billy cap (bowler hat) tipped a little to one side on his head, a black suit, and a heavy silver chain hanging from his waistcoat pocket, in which he kept his watch. He was a real gentleman to me and he spoke in a soft, posh voice that I loved to hear, not at all like an ordinary railway platelayer which he was. My grandma wore a little close-fitting black bonnet with the ribbons tied under her chin and a black cape round her shoulders edged with lace.

My grandad was carrying a long, heavy wooden box. He opened it to show my mother and father, and I got a peep too. In the box was a man’s long leg. It was my uncle Jack’s leg and they were taking it to the churchyard to bury it. My uncle Jack worked at a brickworks in the village of Pimbo Lane; it was his job to work with the locomotives, taking loaded wagons of bricks to the railway sidings across the village lane. The engine always pushed the wagons in front of it and uncle Jack had to ride on the first wagon.

One day, as the train approached the village lane, uncle Jack noticed children playing on the line. He could not signal to the driver to stop because the train was on a curve and he was out of sight, so uncle Jack quickly jumped down from the wagon and ran as fast as he could to the children, throwing them clear of the path of the wagons. Bravely he had saved the children, but unfortunately one of his legs was caught by the wagon wheels and had to be amputated.

The quarry where my father worked closed down and he was out of work. Whatever my father was he was not lazy, and very soon he got a job down a coal mine. But it was too far away to travel to work each day so we had to move from the village. We got a cottage nearer to his work at a place called Bryn, a mile or so from Ashton-in-Makerfield, quite a fair-sized little town. The new house was much bigger than the cottage we had left, and it had gas light in it with the mantles on.

I and my brother and sisters had to go to a fresh school and church not very far from home. To me there seemed a lot more people, and life was a lot busier at Bryn. The electric trolly trams ran through Bryn on to Ashton-in-Makerfield from Wigan. The lads used to jump on the back step of the trams, gripping the handrail and having a ride while the conductor was collecting the fares inside.

Opposite our house, in the fields, was a farm where I spent a lot of my spare time. In the farmyard there was a huge boiler in which potatoes, cabbages and turnips were boiled, and I would keep the boiler stoked up until all the vegetables were nicely cooked. Then with a bucket I would feed the pigs, sometimes eating a potato myself because it was all very good food. Very often I would return home with a bag of potatoes, vegetables and eggs the farmer gave me for my help.

Every Friday night the children were allowed to stay up a little later than usual because on that night Chippy Bill, in his white apron and ringing his bell, would drive into the lane with his horse-drawn mobile chip cart. There was no chip shop in the lane and everybody seemed to wait for Chippy Bill. Of course we could make chips of our own, but there was something special about Chippy Bill’s. We would hang around the cart watching him put potatoes under his chipper to drop in a tin as chips; then he would bend down and, opening the firehole door under his boiler, he would grab his little shovel and put a few nuts of coal on to the fire, the flames sometimes rising out from the top of the chimney peeping out above the roof of his cart.

We didn’t have a long stay at Bryn. We were just about getting used to the place and everybody. My elder brother got married and left us and my sisters started work in a cotton mill at Wigan, having to travel by train and get up very early in the morning. Anyhow, once again a change of environment was on the cards.

My father got out of the mine and started to work at an iron foundry in Wigan. He also succeeded in getting a brand-new terraced house in Wigan, quite near the famous Wigan Pier. The house had a small front garden and a big back yard. It was fitted with gas lights in every room and we had an outside flush toilet. Of course once again it meant going to a fresh school and church, and our family had grown: there was Mother and Dad and six children, two of them working, so we were not quite so badly off now.

For myself, I found the town boys rather different from the country boys: they were more forward and lacked discipline and respect. I saw that it was far easier to get into serious trouble, especially with the police. Petty thieving was a regular pastime, and if one did not take part and concur with the gang one’s life was made miserably lonely. Distracting a shopkeeper’s attention while another of the gang helped himself was an easy game.

Nearby, the main road ran across a bridge over the canal. The gradient was rather steep and the horse-drawn vehicles going over it with a heavy load could only do it at a walking pace. Brewery lorries were a special and easy target for the boys. While the driver concentrated on his horses one of the boys would climb up the back of the lorry, reach over the backboard and hand down bottle after bottle to the fellows running behind. Then we would scamper off in the darkness and enjoy the spoils.

Once an ice-cream vendor left his handcart in front of a pub while he went in for a drink. While one of the lads kept a look-out the others emptied the biscuit tin into their pockets and then filled the tin with ice cream from the tub, quickly vanishing into the fields to devour it.

In the evenings we played all the dirty tricks one could think of just for fun, such as tying a long piece of black cotton to a coin with a hole in it, then throwing it down near the feet of someone passing by on the footpath and drawing it away again as the person began to look around thinking someone had dropped a coin; or tying the handle of a front door to the handle of the next door with a long piece of rope, then knocking at both doors and running off in the darkness as fast as we could. Other tricks were removing garden plant pots from one garden and placing them in a garden lower down the road; or getting a small box and filling it with dog’s excreta and any other muck we saw lying around, then parcelling it up so nice and neat and placing it on the pavement and keeping out of sight to enjoy a good giggle as some person, glancing guiltily around, quickly picked it up, stuffed it under his coat and hurried off home.

Of course gambling on the cards was a must amongst the gang. If we had any money at all it had to go on the cards. We were big boys then and we could make a little pocket money doing all sorts of odd jobs besides the little spending money our parents allowed us. Sat out in the fields, or in any place at all where we could deal out the pack, we played three-card brag, often till late at night.

Soon most of the gang were doing part-time work. I was going the rounds with a milkman each morning before school, knocking on doors and pouring my pints and gills of milk into the jugs left on the doorsteps. In those days milk was delivered on a horse-drawn milk float, with large kits of milk from which the milkman measured his pints and gills. It was a terrible job in winter.

I must have been a decent scholar because one whole year before I was of age to leave school I had passed all exams and learned everything they could teach me, so my headmaster told me, and he gave me a job filling ink pots and running errands wherever they were needed. One nice errand I liked doing was carrying love letters from a teacher at my school to another teacher at a school the other side of town. They provided my train fare and usually tipped me as well.

The year soon passed and my schooldays were over, and it was time to find a regular job. I had not been idle long when my headmaster sent for me. He said to me, ‘Now, boy, have you got a job yet?’ I said, ‘No, Sir.’ He said, ‘Now, look here, take this letter to Douglas Bank Colliery in Woodhouse Lane and give it to the manager. I am recommending you to him as an office boy, and good luck to you.’

I thanked him and off I went to the colliery office, and was taken into the manager’s office. After sending for the cashier to read what the letter said, the manager turned to me and said, ‘Well, my boy, after reading this letter from your schoolmaster I can hardly refuse you the job, so you can start work next Monday morning in the office. You will report to Mr Barnes, the head clerk.’ I thanked him and rushed off home to tell my parents. My mother and father felt rather proud that I was starting work with a collar and tie on, in an office.

I liked the work too and got on well with the other clerks. Very soon I was doing accounts like the other clerks in the office. Then I was given a job of paying out the miners’ wages on a Friday afternoon. The wages sheets were split up, one clerk paying the South Pit men out, another clerk paying all the surface hands. I paid the men of the North Pit. Spread out on my desk, quite easy to handle, was approximately £600. The money was...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Maps

- INTRODUCTION

- BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

- 1 : A Lancashire Lad

- 2 : Going to the Wars

- 3 : Gassed

- 4 : Gallipoli and Egypt

- 5 : The Somme and Blighty

- 6 : Return to France

- 7 : Right Away to Blighty

- NOTES

- Copyright