![]()

Chapter 1

The History of the Cottage Garden

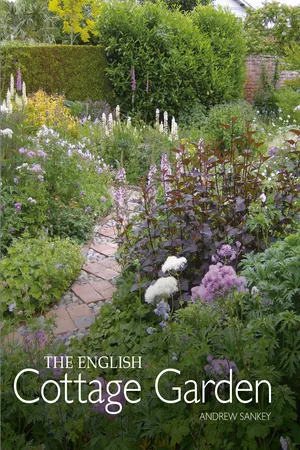

The ‘cottage garden’ is quintessentially English. It immediately brings to mind a quaint thatched cottage with a beautifully scented rose rambling over its door, a neatly clipped hedge with a picket gate and paths with scented flowers spilling over in sweet disorder.

However, the highly romantic style of today’s cottage garden with its borders of traditional flowers intermingled with trees, shrubs, and newer varieties of plants, which are now usually planted in beds around lawns, is a relatively modern form of the cottage garden. This is in complete contrast to the enclosed medieval yard, where beds of vegetables and herbs were simply grown to ensure the poor peasant-cottager could survive on a basic diet of bread, pottage and ale.

Cottage gardens in the past were never consciously designed but evolved over the centuries to fulfil the needs of the poorer classes (labourers, cottagers and village craftsmen) who generally lived a ‘hand-to-mouth’ existence. With little or no wealth to speak of, they took advantage of the native flora, new vegetable introductions and the discarded flowers from the lord of the manor or farm owner for whom they worked.

A beautiful thatched cottage with a garden planted in the traditional cottage style, with roses climbing up the cottage walls and a profusion of flowers spilling over the border under the windows.

THE MEDIEVAL GARTH

Unfortunately, only the important fashionable gardens of the royal and wealthy were ever considered worthy of recording, making it more difficult to trace the early development of the cottage garden. Written evidence about what they grew and how they grew it is scarce. We do, however, know something about the monastery gardens in Europe and can safely assume techniques and flowers filtered down to the peasant-cottagers who worked the land. We can be certain that these early gardens had limited varieties of vegetables and herbs which would have been common throughout Britain. A poor cottager had little need of decorative flowers which weren’t considered essential, although I’m sure a few native plants would have been welcome.

The medieval hovel and Saxon garth.

The Domesday Book (1086) tells us there were vast numbers of garths in England. The word ‘garth’ is an early term for a plot or garden, and they would have varied greatly in size, some being tiny and some of possibly a few acres. The garth was always enclosed: either with a dead hedge, wattle hurdles, a paling fence (vertical posts driven into the ground) or a ‘thorn’ hedge.

Within this enclosure were raised beds for vegetables and herbs. A separate area would have been fenced off for the pig(s) to prevent the animals from eating the precious roots. In the early medieval period, the word ‘vegetable’ wasn’t used – it comes from the French vegetablis meaning to grow and entered the English language sometime in the fourteenth century. Vegetables were called root herbs, worts, leaf beet, or simply referred to by their names – onions, garlic, leek, beets. All these would have been grown in raised beds approximately 1m (3ft) in width being edged with wooden planks or a low wattle fence. This method was probably passed on by the monks, as it was a vital part of the ordered layout within the monastery vegetable and physic gardens. It allowed the free-draining beds to be worked on from either side without compacting the soil.

Reconstruction of a thirteenth-century flint cottage with wattle enclosure for basic vegetables and herbs, at the Weald and Downland Museum.

The small cottages of either wattle and daub or stone, had an earthen floor and thatched roof (no chimney). It was a basic shelter supporting a large family, and during the winter months sheltering the precious animals as well. The village craftsmen and small farmers had similar but larger buildings on a greater area of land and possibly a barn to accommodate the animals. However, everyone gardened and grew the same vegetables and herbs and in general lived on a diet of cabbages, onions, kale and roots (turnips and skirret).

Apart from the vegetables, cottagers had a pig(s), chickens and a few essential herbs they considered worthwhile, which they grew in the garden or up against the cottage. These herbs had three uses: culinary, medicinal and strewing. The strong-tasting herbs were always used for the pot or to flavour ale. Healing herbs were gathered from hedgerows, meadows and woods, but it would have made sense to have the most frequently used medicinal herbs close at hand in the garden, and we know that the monastery and castle gardens had raised beds filled with certain physic herbs. The strewing of herbs mixed with rushes upon the floor was commonplace and helped repel vermin to some extent.

William Langland’s Vision of Piers Plowman, in 1394, states that the ‘croft’ (possibly half an acre behind the cottage) provided a harvest of ‘peas, beans, leeks, parsley, shallots, chilboles [some sort of small onion], chervil and cherries half-red’. Geoffrey Chaucer, throughout his Canterbury Tales, makes mention of ‘beds of wortes’ (root vegetables) and medicinal herbs in the yard.

The Feate of Gardening, a poem from the late Medieval period by Master Jon Gardener, is unique in that it is the first practical guide to gardening. There has been much speculation as to who Gardener actually was, but more important is the information in his work, as he mentions over 100 plants grown in gardens during the period. There is guidance on sowing and setting of worts, seeds and vines; on grafting apple and pear trees; and on when to harvest. I shall not go through the full list of trees, herbs and flowers in the poem, but would like to mention some of the flowers in the section beginning ‘Of other herbs I shall tell’. This includes rue, sage, thyme, hyssop, borage, mint, savory, yarrow, comfrey, valerian, honeysuckle, lavender, cowslip, strawberries, daffodil, primrose, foxglove, hollyhock and peony. It illustrates the use in gardens of both native and newly introduced plants in this period.

If we summarize the medieval plot, we can confidently say it contained basic vegetables, some essential herbs, possibly a few native wildflowers, a few animals (pigs and chickens) and a compost heap. There are no fruit trees just yet (as fruit would simply have been gathered from the wild in season) and no flowers purely for decoration, although wild plants may well have self-seeded around the garden. In this period, all plants had to be of use.

A large swathe of native foxgloves in English woodland.

POTTAGE

‘Pottage’ was the widely eaten food of the cottager, being rather like a thick soup. This consisted of either peas or beans that had been grown in the field strips around the village and then dried. Added to the pottage were any available vegetables or herbs, and a new introduction in the medieval period was the ‘pot marigold’ which became widely grown in cottage gardens, as its petals could be added either fresh or dried to bulk out the pottage.

The most common medieval pottage was ‘bean and onion’. The field bean was a staple of the medieval diet and could be dried and stored for use throughout the year. Onions were the most common vegetable grown in beds and included leeks, garlic, shallots and scallions (a type of everlasting onion).

THE TUDOR AND ELIZABETHAN GARDEN

With the end of the Wars of the Roses and as relative peace returned in Tudor England, gardens began to change. Henry VIII and his court embraced the new knot designs within gardens and welcomed new and interesting flowers and herbs. Vegetables began to be pushed out of the privy garden (private show garden) and instead flowers that were more decorative than useful took their place. Orchards full of new varieties of fruit trees (often purchased from France) became a gentleman’s pride and joy.

Long beds of herbs the Tudors would have grown for culinary, medicinal and strewing purpose in the Tudor Walled Garden at Cressing Temple Barns.

The nosegay garden, full of flowers and herbs found in all gardens of the sixteenth century.

However, it was with the long reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603) that peace and prosperity created a climate of stability that the country had never seen before, and gardening became a great pastime that all classes would benefit from. There was improvement in housing, farming and diet. Herbals, gardening and husbandry books were printed for the first time throughout this period and give us an insight into the advances made in both garden design and the wonderful plants introduced from Europe and the New World. During this golden period the cottage garden starts to take on the form that we recognize as the English cottage garden today.

Thomas Tusser explains the essential work on a farm month by month and gives us a particularly good snapshot of the vegetables, herbs and flowers which he suggests should be grown by the Yeoman farmer’s wife. One Hundred Good Points of Husbandry, although aimed at the relatively wealthy middle-class farmer, lists the flowers and herbs he believes are essential to any garden. These would eventually trickle down to the cottager/labourer throughout this period. Within his book are a number of different lists: seeds and herbs for the kitchen, herbs and roots for salads, strewing herbs and herbs for physic; but the most interesting is a list of herbs, branches and flowers for windows and pots – this particular list confirming the use of flowers for decorative purposes in addition to being useful plants.

The 1580 edition of Tusser’s second book, Five Hundred Pointes of Good Husbandrie, includes: columbines, cowslips, cornflowers, daffodils, sweet briar rose, gilliflowers (red and white), carnations, lavender of all sorts, larkspur, lilies, double marigolds, nigella, heartsease pansy, pinks of all sorts, rosemary, roses of all sorts, snapdragons, Sweet Williams, French marigolds, violets, rose campion, wallflowers, iris and even love-lies-bleeding. When Tusser states these flowers are suitable for windows and pots, I believe that the term ‘windows’ equates to ‘for growing under the windows’ – which of course would make sense as women generall...