This book is available to read until 11th February, 2026

- 332 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 11 Feb |Learn more

About this book

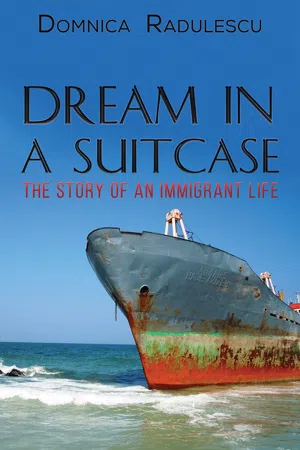

Dream in a Suitcase unravels a fast-paced journey of survival, resilience, and the power of love. It is the first English language memoir of a female Romanian-American survivor of the worst communist dictatorship behind the Iron Curtain. The story offers a rich multicultural mosaic of a life divided not only between two cultures and languages, that of the heroine's native Romania and her adoptive US but also between Chicago's urban culture and that of a small town in Virginia marked by a heavy confederate history. This book is deeply relevant for our times as it offers an opportunity for American-born audiences to develop a deeper understanding for all those who arrived in this country as refugees in search of freedom, peace, and different versions of the American Dream. ENDORSEMENTS: "An extraordinary memoir of fortitude and freedom, a narrative that is vibrant and lyrical. Radulescu takes us from Romania's dark dictatorial past to the world of literature and beauty, back to the landscapes of her beloved native country, then to her new home in America, and always to the geography of the earth. This is an extraordinary read and a covenant to the power of truth and words." Marjorie Agosin, award-winning author of I Lived on Butterfly Hill. "Domnica Radulescu is a courageous writer. Dream in a Suitcase, like her other novels, is a breathless read." Andrei Codrescu, NPR commentator, award-winning poet, and filmmaker.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dream in a Suitcase by Domnica Radulescu in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Trickery of Success

One April towards the end of the 2000s, on the exact day of my father’s birthday, I received an email message from my literary agent whom I had found in an encyclopedia-sized book of literary agents the year before, that had me gasp, hold my breath, and burst into sobs—all in that order. After sixty-four rejections from literary publishers over the course of the previous year, my first novel that emerged from years of tours and detours, searches, creative agonies and ecstasies was not only accepted but ‘bought’ by a major publishing house for a sum larger than my entire annual salary at that point in my life.

The language of the big trade publishing world was new to me, and the fact that somebody was going to pay a five-digit figure for my book manuscript was unbelievable. In the typical manner of the catastrophic thinking of my people, added to the super calamitous thinking of my own family, with the joy came the fear that a tragedy was lurking in the near future in order to balance out the enormity of such an unthinkable success. The power of the two opposing forces battling each other inside my brain kept me in a state of paralysis in front of my computer.

Scared by my sobs, my sons rushed into the room to see what had happened. They laughed mischievously at the news and mocked my crying. “Wow mom, that’s really cool, it’s awesome,” they said almost in unison after which they went on about their business, music, or homework assignments.

Mine was a classic ‘rags to riches’ story, I thought to myself after I calmed down. The girl on the train had pursued and completed her journey and her voice must have touched the chords of an important editor in a New York high rise. Except for my immediate family, I kept the news secret from all friends and colleagues until near the publication date the following year. All the Romanian superstitions came to life in my otherwise supposedly atheistic brain while I was also inwardly gloating.

Over the next months, publishers from all over the world were throwing tens of thousands of dollars, euros, and British pounds to publish my novel in widely spoken or small circulation languages, from French and German to Dutch, to Hebrew and Lithuanian. Two British publishers competed over my book in an auction, and I gave it to the one that also paid me to write my next novel.

For sure, my writing career was set, and it could only keep ascending for as long as I had stories to tell and novels to contain those stories. If only my father were still alive to see me now, if only my aunt Mimi who died alone in her Bucharest apartment during our first summer in Chicago could see me now. I was vindicating my father’s unpublished poetry books, my aunt’s un-produced plays, all the writers and dreamers in my family.

I was the first Romanian in America with such meteoric novelistic success, not to mention the two acres of land that I owned behind my historic house. I was also vindicating my own miseries created by my relationships with university colleagues who had been mean and hostile, had put me down or treated me as invisible, had spoken behind my back, had stuck their noses into my private life only to punish me for it in the workplace, and had tormented me with myriads of hostilities before my tenure.

Maybe now finally, I could leave my teaching job at the small southern university and teach at a prestigious university in a big city away from the stupid confederacy. Still, I held my glorious secret like a precious baby, both vulnerable and delicious, protecting it from evil spirits, jealousies and envy, walking the streets of my town with a new bounce in my step and a mischievous smile.

My older son was finishing high school and my younger one middle school, moving through stages, rites of passage, puberty, first girlfriends, preparations for college for one and for high school for the other. It was a chaotic and whimsical spring, with heavy rains and flash floods, outbursts of wicked sun, stridently pink and magenta dogwoods, and red buds in bloom. On top of the news of publication I also received an international fellowship to teach in Romania, at the university located in my mother’s native town, deep in the heart of Transylvania.

I was at the top of my game for sure, yet the accumulation of success brought with it incomprehensible fears and restlessness. My sons were restless too in their burgeoning bodies and confused teenage spirits, and as usual, I absorbed all their anxieties and ecstasies, their highs and lows, while also attending all their games, recitals, concerts. I tried to breathe in unison with them hoping my breath will keep them safe and protected.

From the first installment of my advances, I paid off all my debts writing huge four and five-digit checks like I had never done in my life, feeling like I finally matched in income the majesty of the house I was living in, which some people in town were still resentful I owned because they had wanted it for themselves. Or that was my perception, based partly on rumors, partly on comments made directly to me by these kind people.

One afternoon that spring after returning from one of my younger son’s games and stopping for a bite to eat in a neighboring town, the friends who were accompanying us received a message on their cell phones that a high schooler, possibly two, had drowned in the river at a dangerous junction near the dam where the waters were furious because of the recent rains. I knew by name and face both kids mentioned. In a small town, everybody knows everybody’s children.

These were kids I had seen at piano recitals, band concerts, end of school years celebrations, games, hanging out on the benches in the little park in the center of town. I had seen them grow from toddlers to awkward looking pre-teens to apathetic or hyperactive teens. The mood at the table of an Indian restaurant in a mall by the side of an interstate became gloomy. I had one child with me while the other was still in town, possibly at Lacrosse practice, or playing music with his friends, or just hanging out.

The area around the river junction where the two youth might have drowned was a popular spot where kids and teens practiced their various sports, bathed in the river, or listened to music blasting from their pickup trucks. It had once been a lock, a point of passage for the flat boats going down the river with merchandise in the previous century, maybe even a point through which one or two slaves from the tobacco plantations might have tried to escape. Good for them! Heavy southern histories simmered under every stone, at every corner, at every bent of the river in that town and county that was now my home.

No plantation owners had been in any of my lineage, and I had enough of my own European histories of fascism and communism to contend with. I used to love waiting for my kids at that point of the river, watching groups of middle-schoolers and high-schoolers laugh, playfully push each other around, smoke secretively—being young in America—something I had never been and had always voraciously wanted to have been.

As we were delving into our Indian curries and nan bread that afternoon, the father of my son’s friend, the same one who had invited the sheriff to my doorstep a couple of years earlier with his naughty phone calls, sent a text message about the status of the search for the two boys. One had survived, while the other was swallowed by the furious waters. After many panicked attempts, I was able to reach my older son who told me he happened to be at the famous spot by the river with his friends.

His biology teacher and another musician friend of his were the ones who had saved one of the two boys but lost the other one. The waters were too swollen. The boy got entangled in algae and was carried by the current down the river towards the dam. They couldn’t find his body. I cringed and bent over at the image of the young boy entangled in algae, trapped and drowned at the bottom of the muddy flooding river waters. My son was drowned in sadness. He knew the boy, red-headed, a talented pianist and consummate swimmer and scuba diver.

Upon our return to town that evening, the bridge across the river was filled with townspeople looking over the rails as if searching for the lost child, and police cars, ambulances, fire trucks were blocking the entire area. An ominous gloom enveloped the town over the following days, as teams of rescuers and professional divers from neighboring cities had come to find the body of the lost boy.

I stayed as close as I could to my sons, dreading, like all the other parents in town, what it would be like to find ourselves in the shoes of the lost boy’s parents. A tragedy in a small town took on an entirely different rhythm and shape than in a big city. Life, death, birth, all the rights of passage acquired a wrenching poignancy and stridency. They hit you in the gut whether you wanted it or not, because it all happened right next to you and because you knew everybody.

The news of the many international deals for my novel flooding my email inbox seemed almost offensive at that time, irrelevant and unimportant. The last line from the play Oedipus Rex kept ringing in my head during those days, “Do not consider yourself a happy man until you have lived your last day on earth.” I translated it into, “Do not get arrogant and too sure of your success, and do not gloat because misery can strike at any time”.

The refugee that I was knew better how to deal with difficulties and obstacles than with success and happiness. That refugee girl was going to be forever mistrustful of the stability of happiness. And the tragedies that were looming over the little town where I had ended up, were the very proof of that. Even though I held idealized images and fantasies of what it would have been like to grow up in America, I felt that everything bad was happening now precisely because of America. The recklessness of it, the fixation on the independence of children before they were fully cooked human beings, the carelessness of the parents, the cars, the booze, the obsessive athleticism, the bad temptations of drugs, porn, guns.

I had horrific fantasies of my children being swept away by the mad currents of all that like the red-haired boy being swept away by the current of the swollen river. The spring before, a girl who had babysat for my children had been killed in a car accident driving with her boyfriend from the prom. They were sixteen-year-old children. And still that same spring, a month later, a high school boy shot himself in the head with his father’s gun. So much for how safe and nice a place to raise your children our town was! It all felt dark and wickedly unsafe to me.

With each one of those accidents, a barrage of sickening clichés would start circulating about ‘the town coming together’ and ‘praying for the family’. Vigils and romanticized gatherings of the high school friends and classmates were held in one of the pretty natural spots around town. It all seemed fake and misguided. I would have wanted to see dark mourning and loud wailing across town, a long cortège of wailers with no words.

As the town was filling up with rich white retirees settling into expensive mansions to spend their old age in the quaintness of the town and move between the proliferating banks and churches in their luscious sedans, stocky and severe looking cops kept multiplying and making sure no teenagers were ‘loitering’ at street corners or on the park benches to spoil the pristine look of the town. It wasn’t clear where other than their parents’ basements were those kids supposed to spend their free time when they weren’t running and hitting a ball on the playing field. I started hating the entire notion of the ‘nice community’ and ‘the nice town’.

I was hoping that my writing success was going to allow me to take my teenage boys away from that provincial setting, sell my coveted property for a mega sum, and move back to my first American city: the rowdy, windy, bustling Chicago amid all the pollution, traffic and noise. For sure now that I was a rising star in the big trade publishing world, I should have more career choices, be hired by a bigger university in a real city.

And yet, I was becoming more entrenched in the town with every new spring and every new graduation, high-school prom, sports season, summer camps, first dogwoods in bloom, then lilies in bloom, then irises bursting in their mauve glory. The plant cycles enmeshed with our lives, the lives of the Romanian speaking family in the big sheriff’s house. I had witnessed the tragedies of the town, cried for its prematurely lost youth, rejoiced or cringed at band concerts and Christmas parades.

Every street and corner of the town quivered with memories of my children at different stages of their lives. And as I became more entrenched in our American small town, I was also spreading my tentacles across the ocean back into my native land in my insatiable voraciousness for home, land, the totality of me.

I was preparing for my six months away with extraordinary anticipation. My children were rooting me in American soil with every step, yet precisely because of that, I needed more than ever to search for the childhood and young adulthood I had left behind one September day in 1983. It always came back, hopelessly—the day of my departure, the last goodbyes, the suitcase, the heartache, the airport, the customs officers, the suitcase again, the airplane to Fiumicino Rome, the arrival in Rome ready to forget everything and begin everything.

The girl on the train had luckily come to life during that first decade of the new millennium and was now on her own, ready to go out into the world and unfold her story of love, escape, train rides, heartbreak, new beginnings, America, and to return after twenty years. Her story was complete, but I was not. Her story was making me a lot of money but was not making me whole. My life of doubles, of returns and back-and-forth journeys between native and adoptive lands was only starting.

That spring and summer of my big breakthrough in the American literary scene, of the tragedies in my hometown, of preparations for my older son’s going away to college, and of my own preparations for a temporary simultaneous existential re-rooting/uprooting, life unfolded in a rollercoaster of unprecedented thrills and anxieties. Publishers from across the world were enticing me with book deals and contracts, with thousands of dollars that were wired into my bank accounts and plans for glamorous book tours, interviews, choices of book covers.

They ‘loved’ my story. They all said that ‘the voice is so unique’, the style ‘so lyrical, so poetic’. They all marveled at how ‘amazing’ it was that I wrote in English so well. The line about my good English always sounded more like an insult than a compliment. I was the non-native speaker, the one speaking English as a second language. Among the many editors who had earlier rejected my manuscript, there were often those who praised the mastery of my English ‘despite’ my non-native status and yet wrote their rejection letters in worn-out clichés that to my non-native ear sounded rather simplistic and repetitive coming from a native speaker with an editing job at a major American publishing house.

I remembered one of my graduate school professors in Chicago who once told me I was never going to be able to teach English literature in an American university because of my foreign accent, so I should consider pursuing my degree in Romance languages instead of comparative literature which had been my desire. I was wickedly thinking now that if I ever saw her, I would say to her something like, how many international presses are paying thousands and tens of thousands of dollars to obtain translation rights to your insipid books of literary theory?

I didn’t allow myself such gloating pleasures too often though both out of ancestral beliefs of impending catastrophe and out of very contemporary anxieties about splitting my already thinly spread family in two: one son going to college in America, the other accompanying me to Romania. In between the two stretched the unfathomable chasm of ocean waves and continents.

The following months galloped at a dizzying rhythm, punctuated by more heartaches and thrills. Taking my older son to college, getting him settled, and leaving him in his tiny college dorm room, his brother bursting into tears and saying ‘it’s the end of an era’, just days before we were leaving on a six-month adventure back to the country I had run away from at full speed twenty-five years earlier—it all came with a sour taste of freshly cut wounds, like the taste of blood in your mouth after a hard fall or a hit.

A deep rattling confusion was taking hold of my entire being and a sense of breakage, of crumbling homes like the sound of broken glass years earlier when my younger son kicked his soccer ball full force through the front door. Shattered glass, it all sounded and felt like shattered glass in my heart and in the new reality I was plunging into.

All throughout departure preparations, my new editor from the big New York press would send me copious editorial notes about how I should revise, rewrite, cut this part here and this part over there, this one is too jarring, this other one is too slow, too lyrical, not lyrical enough, too detailed, not detailed enough. What year exactly did this character take this trip, what color of eyes did this character’s friend have? There was always too little of something, too much of something else.

I should have known it all came at a price: the money, the sudden low-grade fame in the larger scheme of fame, the breakthrough of a lifetime for me. The proverbial selling of your soul to the devil. Selling a bit of yourself and of the very writing that brought you where you were, in exchange for what? Money? My work, my story, my voice became the property of the publisher, and I had to play by those rules of commodification if I wanted the success. And boy did I want the success. Why else had I left everything and everyone a quarter of a century earlier if not for that kind of success?

A basic truth became clear during the months prior and post publication of my first novel; I could have had marriages, divorces, children, even a post revolution house in my native land, but the writing success was the overriding reason for the brutal choice I had made as a young woman. The much idealized yet not to be taken for granted freedom of speech, freedom of expression, blah, blah, blah. I had left with the unpublished volume of short stories titled Yes but Life in the mythic suitcase, with one thought towering above all others, I will become an important writer one day, an artist!

I was now damn close to that initial dream, yet the question of true freedom of expression became tricky, without a clear-cut answer. It was a larger cell with movable walls, a larger cage, but still a cage. One form of censorship took the place of another. An imaginary Reader was always invoked for every chunk of writing I was asked to take out or transform, “this chapter is confusing for the reader”, “you have to make this clearer for the reader”, “the reader will have a hard time with this passage”.

I didn’t know who that Reader was and didn’t care a bit about them. If such a Reader ...

Table of contents

- Dream in a Suitcase

- About the Author

- Dedication

- Mottos

- Copyright Information ©

- Acknowledgments

- The Escape

- Beginnings

- The Arrival of Zoila Valdivieso

- My America Now

- Welcome to America

- My ‘Roma Cita Eterna’

- The First Summer in Chicago, 1984

- Love and Landscape

- Graffiti and Chicago Trains

- Accident with a Nun

- Mango – Very Good Fruit

- Overworked Working Mother

- Marriage on the Blue Ridge

- Abortions

- Coming Out of the Six-Year Hangover

- Turns and Returns

- Big Return, Big House

- The Black Sea, 1983

- Farewells and New Beginnings

- The Trickery of Success

- Love, Death, and Chicago – All Over Again

- Loose Ends

- The Delights of Provence

- Our Town

- The Romanian Reunion

- Entangled Roots, New Suitcase