John M. Lamberta,b and F. L. van Delft,c

1.1 ADCs – A Historical Perspective

Globally, about 1 in 6 deaths occurs due to cancer, and it is the second leading cause of death in the world. According to estimates from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC),1 there were 17 million new cancer cases and nearly 10 million cancer deaths worldwide in 2018, while by 2040, the global burden is expected to grow above 16 million cancer deaths, mostly due to the growth and aging of the population and the increasing prevalence of risk factors like smoking, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and fewer childbirths, in economically transitioning countries – a concerning development.

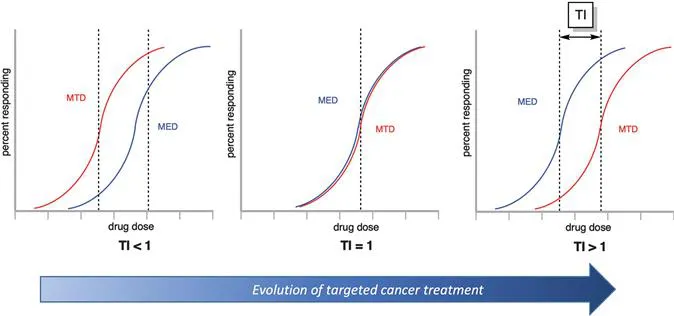

On the positive side, there are many ways to treat cancer, ranging from surgery to radiation therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, hormone therapy, and stem cell transplant. For solid tumors, the most effective therapy is usually surgical removal, often in combination with adjuvant chemotherapy. In the case of metastatic disease, chemotherapy is generally the only option, and it is rarely curative. For hematological tumors, surgery is not an option, and chemotherapy is typically the standard of care. However, chemotherapeutic drugs are limited by undesired toxicities, which leads to systemic side effects. In fact, all chemotherapeutic drugs are administered at doses that are barely tolerated by patients, but nevertheless well below desired therapeutically active levels (see Figure 1.1, left). A recent review concluded that most of the anti-cancer drugs that entered the market between 2009 and 2013 showed only a marginal gain in terms of overall survival, so there is an urgent need to increase therapeutic efficacy with more effective and safer anti-cancer drugs.2 Thus, improved anti-cancer drugs are highly desirable to offer an improved prognosis for cancer patients.

Figure 1.1 Determination of therapeutic index (TI) based on relationship between maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and minimal effective dose (MED).

One class of drugs that has gained major interest in the biopharmaceutical industry is targeted cancer treatment with therapeutic antibodies. Since the advent of hybridoma technology,3 monoclonal antibodies can be mass produced, and antibody-based treatment of cancer has established itself as one of the most successful therapeutic strategies for both hematologic malignancies and solid tumors, with 30 monoclonal antibodies approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of cancer.4

In the past 30 years, huge efforts have been made to merge the positive features of biological therapy and chemotherapy in the form of an antibody–drug conjugate (ADC). The concept hinges on the idea of utilizing target-specific antibodies as vehicles for the delivery of highly cytotoxic drugs directly at the tumor site but not to healthy tissue, thus increasing efficacy and reducing toxic adverse events. The concept is inspired by the ‘magic bullet’-theory first proposed by Paul Ehrlich over a century ago.5,6 Ehrlich coined the vision that it should be possible to administer a therapeutically effective dose of a cytotoxic compound targeted via an agent of selectivity to a specific subset of diseased cells in a living organism without evoking systemic toxicity, thereby effectively enhancing the therapeutic index of traditional chemotherapy (see Figure 1.1, right).

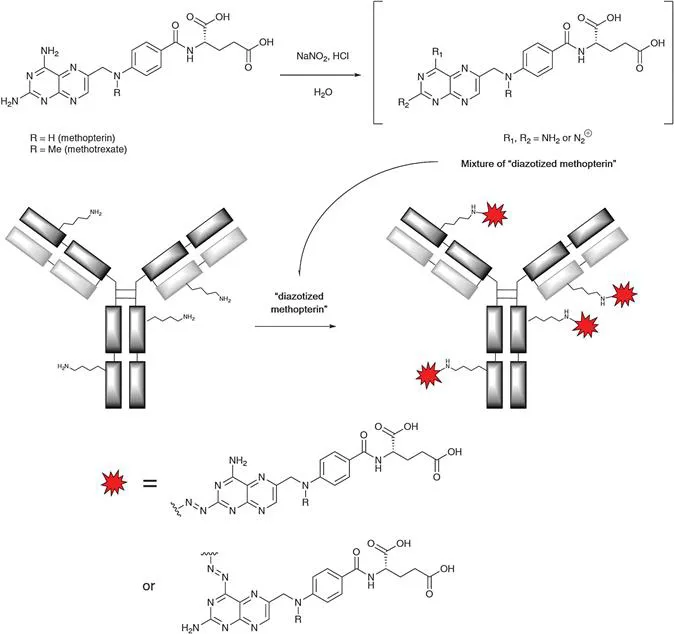

The challenge of realizing a true magic bullet concept employing an antibody as the agent of selectivity becomes clear from the fact that it took so many years until the first ADC was approved (Mylotarg® in 2000). In 1958, the French oncologist Georges Mathé and his colleagues were the first to investigate the concept of curing xenografted mice through the administration of a mixture of antibodies, chemically modified with a cytotoxic drug.7 Specifically, antibodies were isolated from the blood of hamsters that had been immunized with leukemia cell line 1210. Separately, methopterin (N-demethyl methotrexate) was subjected to diazotization, then combined with the isolated pool of hamster immunoglobulins (IgGs), thereby providing the envisaged antibody conjugates through the reaction of lysine sidechain amino groups with the diazo-derivative of methopterin (see Scheme 1.1). The resulting mixture was administered at a dose of 125 mg kg−1 to mice that had been grafted with leukemia 1210 on the day before dosing. It was found that ADC-treated mice survived longer (14–16 days), and their tumors shrank versus the appropriate controls (max. 10 days of survival with growing tumors).

Scheme 1.1 Diazotization of methopterin followed by addition to antibody for generation of first-of-a-kind antibody–drug conjugate.

It was clear to Mathé that a fundamentally new approach to cancer treatment had been revealed by this experimental result when he wrote: “Une nouvelle méthode générale de chimiothérapie semble ouverte: transporter électivement, par des -globulines de serum immune, des agents chimiques actifs jusqu’à l'agent pathogène ou aux cellules maladies, au moyen d'une function amine diazotable ou d'une autre combinaison chimique dont la recherche est en cours.” In English: “A novel general method for chemotherapy appears feasible: the effective transport of an active chemical substance, by means of gamma-globulins from immunized serum, to a pathogenic agent or cancerous cells, by means of amino group diazotization or another chemical modification”.

In the 1960s, Mathé's concept was expanded by a group at the Rand Development Corporation (Cleveland, Ohio), where methods were developed for the chemical coupling of a variety of chemotherapeutic agents to immunoglobulins.8 This new approach of cancer treatment was picked up by a group of surgeons and pathologists at the Victoria General Hospital in Halifax (Nova Scotia, Canada) in 1972, who likely were the first ever to treat a cancer patient with an ADC, albeit with the chemotherapeutic compound bound by adsorption to the antibody carrier, rather than by covalent coupling.9 In a case report, it was described how a patient with disseminated malignant melanoma was injected, first locally and then systemically, with anti-melanoma immunoglobulin to which the nitrogen mustard chlorambucil was bound. The single patient trial had a good outcome: all metastatic nodules regressed. Eli Lilly and Company were then the first pharmaceutical firm to expand upon the pioneering work of Mathé7 and Ghose,9 with a clinical feasibility study on the preparation of a conjugate of vindesine covalently linked to a sheep anti-CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) immunoglobulin.10 The invention of monoclonal antibody technology by Köhler and Milstein3 in the mid-1970s enabled the true birth of the ADC field, moving beyond the coupling of chemotherapeutic agents to crude immunoglobulin serum fractions. In the years to follow, particularly in the mid- to late-1980s, multiple attempts were made to advance the concept into the clinic,11 conjugating monoclonal antibodies having defined target specificity with a large range of cyt...