eBook - ePub

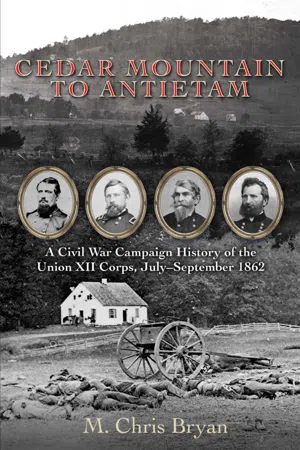

Cedar Mountain to Antietam

A Civil War Campaign History of the Union XII Corps, July–September 1862

- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cedar Mountain to Antietam

A Civil War Campaign History of the Union XII Corps, July–September 1862

About this book

This history of the Union XII Corps "skillfully weaves firsthand accounts into a compelling story about the triumphs and defeats of this venerable unit" (Bradley M. Gottfried, author of

The Maps of Antietam).

The diminutive Union XII Corps found significant success on the field at Antietam. Its soldiers swept through the East Woods and the Miller Cornfield—permanently clearing both of Confederates—repelled multiple Southern assaults against the Dunker Church plateau, and eventually secured a foothold in the West Woods. This important piece of high ground had been the Union objective all morning, and its occupation threatened the center and rear of Gen. Robert E. Lee's embattled Army of Northern Virginia. Yet federal leadership largely ignored this signal achievement and the opportunity it presented.

The achievement of the XII Corps is especially notable given its string of disappointments and hardships in the months leading up to Antietam. M. Chris Bryan's Cedar Mountain to Antietam begins with the formation of this often-luckless command as the II Corps in Maj. Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia on June 26, 1862. Bryan explains in meticulous detail how the corps endured a bloody and demoralizing loss after coming within a whisker of defeating Maj. Gen. "Stonewall" Jackson at Cedar Mountain on August 9; suffered through the hardships of Pope's campaign before and after the Battle of Second Manassas; and triumphed after entering Maryland and joining the reorganized Army of the Potomac.

The men of this small corps earned a solid reputation in the Army of the Potomac at Antietam that would only grow during the battles of 1863. This unique study, which blends unit history with sound leadership and character assessments, puts the XII Corps' actions in proper context by providing significant and substantive treatment to its Confederate opponents. Bryan's extensive archival research, newspapers, and other important resources, together with detailed maps and images, offers a compelling story of a little-studied yet consequential command that fills a longstanding historiographical gap.

The diminutive Union XII Corps found significant success on the field at Antietam. Its soldiers swept through the East Woods and the Miller Cornfield—permanently clearing both of Confederates—repelled multiple Southern assaults against the Dunker Church plateau, and eventually secured a foothold in the West Woods. This important piece of high ground had been the Union objective all morning, and its occupation threatened the center and rear of Gen. Robert E. Lee's embattled Army of Northern Virginia. Yet federal leadership largely ignored this signal achievement and the opportunity it presented.

The achievement of the XII Corps is especially notable given its string of disappointments and hardships in the months leading up to Antietam. M. Chris Bryan's Cedar Mountain to Antietam begins with the formation of this often-luckless command as the II Corps in Maj. Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia on June 26, 1862. Bryan explains in meticulous detail how the corps endured a bloody and demoralizing loss after coming within a whisker of defeating Maj. Gen. "Stonewall" Jackson at Cedar Mountain on August 9; suffered through the hardships of Pope's campaign before and after the Battle of Second Manassas; and triumphed after entering Maryland and joining the reorganized Army of the Potomac.

The men of this small corps earned a solid reputation in the Army of the Potomac at Antietam that would only grow during the battles of 1863. This unique study, which blends unit history with sound leadership and character assessments, puts the XII Corps' actions in proper context by providing significant and substantive treatment to its Confederate opponents. Bryan's extensive archival research, newspapers, and other important resources, together with detailed maps and images, offers a compelling story of a little-studied yet consequential command that fills a longstanding historiographical gap.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cedar Mountain to Antietam by M. Chris Bryan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

II Corps, Army of Virginia From Little Washington to Washington, DC July 28 to September 3, 1862

“When sorrows come, they come not single spies But in battalions.”

— Hamlet, Act 4, Scene 5

Chapter 1

“The stupidity of past follies must be atoned for by energetic blows.”1

— James Gillette, 3rd Maryland

Banks’s Corps from Little Washington to Culpeper Court House

July 28–August 7, 1862

On the clear morning of July 28, 1862, near their camp outside the rolling hills near Little Washington, Virginia, Maj. Gen. Nathanial P. Banks’s forces underwent extensive drills. Banks arrayed 5,000 infantrymen on a 60-acre field, and the troops stood in defensive squares, confronting both charging cavalry and the sweltering Virginia heat. The Yankee cavalry failed to disperse the infantrymen, twice charging furiously and not breaking off until nearly on their comrades’ bayonets.

Alonzo Quint, chaplain of the 2nd Massachusetts, described these Napoleonic-era anachronisms as “sham fights” that occurred after Banks reviewed and drilled all the units in his camp: 12 infantry regiments and 50 artillery pieces. A Pennsylvanian described the men as being “in good trim and all alacrity to obey the commands,” which Banks issued in his “clear, deep tone of voice.”2

“Grand Review of N. P. Banks’ Corps at Little Washington, Va,” on July 28th, 1862, Edwin Forbes. Library of Congress

Banks was proud that he had personally directed the entire command and told his wife he felt as if he had been doing it all his life. This was not so. Despite his lofty rank, Banks lacked military experience. He was a “political general,” a former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives and Governor of Massachusetts who gained his major general’s commission via his political connections. Before properly learning the mechanics of his new trade, he had seniority over most other major generals. Banks’s military service began in Baltimore, where he successfully quelled secessionist rumblings. He was then given command of the Department of the Shenandoah, furtively dispatching the 3rd Wisconsin to Frederick, Maryland, to arrest a cabal of secessionist state delegates.3

The following spring, Banks followed Stonewall Jackson south, up the Shenandoah Valley, and established a garrison down the valley at Strasburg, Virginia. In late May, Jackson threatened Banks’s lines of communication, precipitating the latter’s unnecessarily tardy withdrawal to Winchester. Banks and Brig. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams, commanding the sole division present, entered Winchester that evening. Units that had fought rearguard actions on the retreat showed up later. The 27th Indiana and 28th New York finally arrived at 11:00 p.m., and the 2nd Massachusetts dragged in at 2:00 a.m. Williams’s brigade commanders, Cols. George H. Gordon and Dudley Donnelly, stayed on the field all night, preparing for possible Rebel attacks.4

When Jackson, who outnumbered Banks three to one, arrived at dawn, he turned Banks’s flank and pursued the Northerners through the streets of Winchester while citizens fired at the Yankees from windows. After a grueling, day-long march from Strasburg and a demoralizing drubbing at Winchester, Banks’s troops now trudged another 35 miles to safety on the Potomac’s north shore at Williamsport, Maryland. Though many of his soldiers still firmly trusted Banks, this latest experience soured others. Captain Richard Cary, a company commander in the 2nd Massachusetts, wrote disgustedly in late June that, “Being under Banks is very much like being in company with a drunken man who flourishes a revolver. You may be shot at any moment & then not have the satisfaction of knowing it was intentional but owing merely to your excited friend not knowing what he was about.”5

Banks soon returned to Virginia, and when Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia was created on June 26, Banks’s reorganized, two-division command became its II Corps. Banks made widespread changes in corps leadership during this time. After the Winchester defeat, Brig. Gen. Samuel Wylie Crawford supplanted Col. Donnelly in command of Williams’s 1st Brigade. Donnelly reassumed command of the 28th New York. The brigade’s soldiers, who invariably thought well of Donnelly, resented this change. Two brigades, which constituted two-thirds of Brig. Gen. Christopher C. Augur’s 2nd Division, joined the command near Amissville on July 10. Brigadier Generals Henry Prince and George S. Greene assumed command of these brigades, neither of which had seen serious action. Augur also had recently joined his command, which reached Little Washington on July 19, two days after the rest of Banks’s corps. On August 1, a final brigade, under Brig. Gen. Erastus Tyler, was placed in Augur’s division. Brigadier General John W. Geary assumed command of the brigade, and Tyler left the corps. Geary’s former command, the 28th Pennsylvania, joined four veteran Ohio regiments that had fought Jackson at Kernstown and Port Republic.6

In late June and early July, Banks’s troops devastated the ubiquitous cherries and blackberries growing in the region. On the march to Amissville on July 7, each man in the company marching ahead of the 10th Maine slung a cherry tree bough over his shoulder, reminding Lt. John Gould of the moving forest fulfilling the witches’ prophecy to Macbeth. Tragic allusions aside, it was a relaxing time for Banks’s corps. Gould and his comrades enjoyed a “picnic life” in the forest near Amissville. All were cheerful and rations plentiful. “The woods ring continually with a thousand laughing voices, or echo the tunes of the bands.” Colonel George Cobham, who could hear the dozen regimental bands playing within earshot, thought the evenings “very pleasant.” A staff clerk’s mistake, however, briefly halted this relaxing time, resulting in the corps marching toward Warrenton rather than its correct destination of Little Washington, north of the Rappahannock. The corps found a “cheerless and devastated country.” In but six weeks hence, they would be here again.7

After reaching Little Washington, Williams’s division began complaining about its placement. Captain Richard Cary griped, “We have got a beastly camp ground on the side of a steep hill & just where the line of battle is intended to be in case of a fight. . . . Neither Crawford nor Gordon wanted to camp here.” One of Banks’s aides quashed these protests, and the division remained there until July 25, when it moved to a spot closer to the 60-acre drill field. Except for the oppressive heat, Cary was mostly satisfied with the new camp. He wished he had a, “Scientific interest in bugs of which I have always on hand—or rather all over me—in my tent a very large & choice assortment including every variety.”8

At its new camp, the soldiers affected more than the population of cherries. General Gordon sympathized: “Our camps generally were established in the neighborhood of quiet farms, which we occupied and overran, until we became a great unnatural plague to the people. We filled their woods with our tents, we killed their sheep and calves, and substituted, for the ‘drowsy tinkling of their lowing herds,’ the beating drum, the ear-piercing fife, and all the loud alarum of war.” According to its regimental history, darkness brought, “in some way,” a variety of livestock and vegetables into the 60th New York’s camp. Lieutenant James J. Gillette, commissary officer for Prince’s brigade, heartily disdained his fellow soldiers’ behavior:

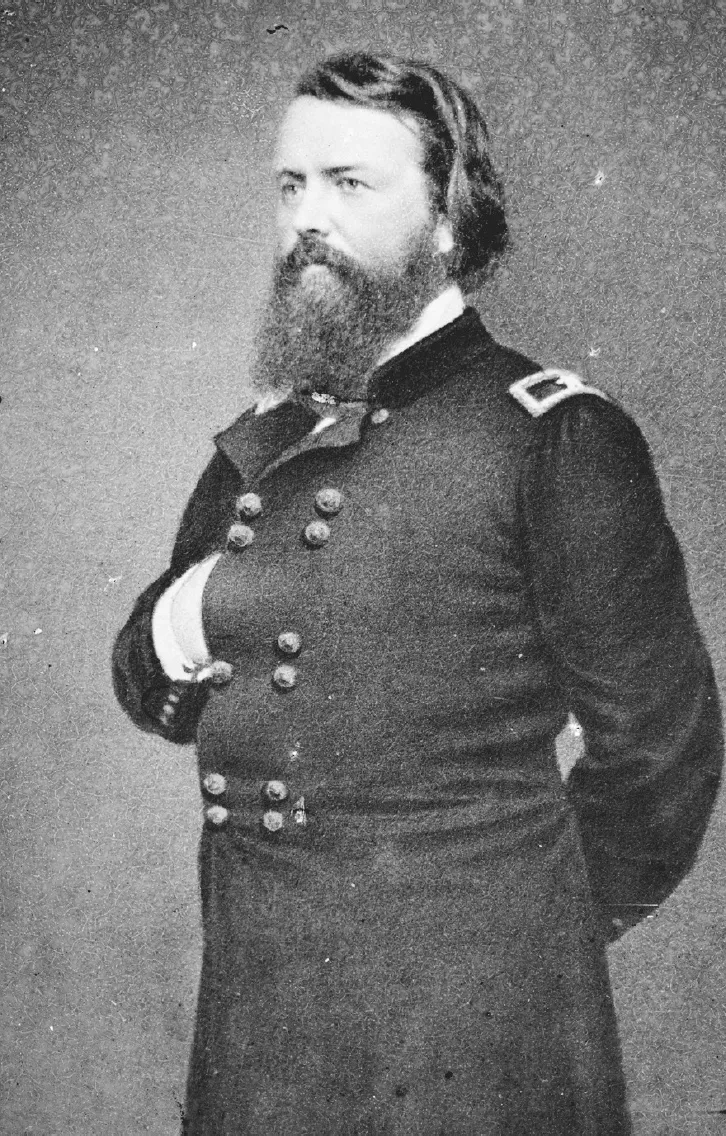

Maj. Gen. John Pope, Army of Virginia Library of Congress

Straggling soldiers have been known to rob the farm houses and even small cottages. The homes of the poor of every ounce of food or forage contained in them. Families have been left without the means of preparing a meal of victuals. . . . The anxieties, privations and discomforts of those removed from the scene of wars conflicts, away from the path of armies know nothing of the suffering or inconveniences compared with the horrors undergone by the people of Virginia. . . .The lawless acts of many of our soldiery are worthy of worse than death. The villains urge as authority: Gen Pope’s order.9

***

Major General John Pope graduated from West Point in 1842 and was twice brevetted in the Mexican War. He achieved success in the Western Theater in the early days of the Civil War, capturing New Madrid, Missouri, and Island Number 10 on the Mississippi River. Lincoln brought him east during the Army of the Potomac’s glacially slow march up the York-James peninsula, southeast of Richmond. Pope’s mission was to coordinate and focus the scattered and hitherto ineffective forces operating in and around the Shenandoah Valley. Their common opponent, Stonewall Jackson, had temporarily quit the Valley to support Robert E. Lee’s defense of Richmond. On June 26, the commands of Banks and Maj. Gens. John C. Fremont and Irvin McDowell were consolidated into Pope’s Army of Virginia. East of Richmond, Lee’s forces were fighting the “Seven Days” battles, which resulted in Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s “change of base” from the York to the James River.10

The Army of Virginia was charged with covering Washington and relieving the pressure on McClellan’s Army of the Potomac at Harrison’s Landing on the James by threatening Lee’s supply line on the Virginia Central Railroad near Gordonsville. Pope concentrated his army on a line from Sperryville to Fredericksburg. Major General Franz Sigel, Fremont’s replacement, camped at Sperryville. Banks was southeast of Little Washington, to Sigel’s east, and yet further east, McDowell’s corps was strung out along the Rappahannock River from Waterloo Bridge to Fredericksburg. Pope remained in Washington and issued a flurry of orders. Pope directed his men to subsist off the land in order to “secure efficient and rapid operations,” but his orders gave rise to the unrestrained foraging that Union officers struggled to constrain. General Orders Nos. 7 and 11 decreed draconian measures, such as burning houses of civilians from which Union troops were ambushed, executing oath violators, and forcing the populace to repair guerilla damage.11

Pope’s orders, sanctioned by the Linco...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Maps

- Archival Sources

- Introduction

- Part I: II Corps, Army of Virginia from Little Washington to Washington, DC, July 28 to September 3, 1862

- Part II: XII Corps, Army of the Potomac from Chain Bridge to the Dunker Church September 4 to 30, 1862

- Epilogue: Beyond the Antietam

- Appendix A: Orders of Battle

- Appendix B: Casualties and Force Strength

- Appendix C: Where the Advanced 3rd Wisconsin Battalion Fought at Cedar Mountain

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author