- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

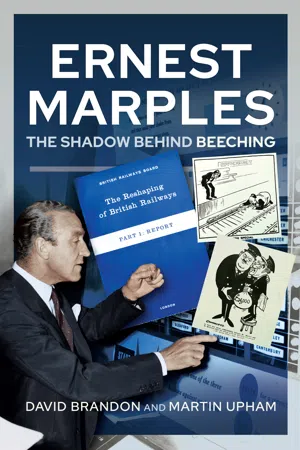

This biography examines the life and career of the conservative politician who led the charge to reshape British Railways in the mid-twentieth century.

Ernest Marples was one of the most influential and controversial British politicians of the mid-twentieth century. As the Minister of Transport (1959–1964) he appointed Dr. Beeching chairman of British Railways and commissioned him to produce his infamous "Beeching Report". Earlier, as Postmaster General (1957–1959), he reformed Post Office accounting systems and launched postcodes and Subscriber Trunk Dialing.

Though Marples evaded implicated in the Profumo Affair which rocked the Conservative Party, his political career was over soon afterwards. Questionable business practices, and a 1975 flight to Monaco, drew scrutiny from Inland Revenue. Beeching, unhappy under a Labour government, returned to private industry.

This biography of Marples draws on newly-available archives to examine Marples's career as well as public and private transport policy, the growing power of the pro-road lobby, and the successful campaign to identify personal freedom with driving.

Ernest Marples was one of the most influential and controversial British politicians of the mid-twentieth century. As the Minister of Transport (1959–1964) he appointed Dr. Beeching chairman of British Railways and commissioned him to produce his infamous "Beeching Report". Earlier, as Postmaster General (1957–1959), he reformed Post Office accounting systems and launched postcodes and Subscriber Trunk Dialing.

Though Marples evaded implicated in the Profumo Affair which rocked the Conservative Party, his political career was over soon afterwards. Questionable business practices, and a 1975 flight to Monaco, drew scrutiny from Inland Revenue. Beeching, unhappy under a Labour government, returned to private industry.

This biography of Marples draws on newly-available archives to examine Marples's career as well as public and private transport policy, the growing power of the pro-road lobby, and the successful campaign to identify personal freedom with driving.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

From Lancashire to the Army 1907–1945

Ernest Marples was born at 45 Dorset Road, Levenshulme (now Greater Manchester) on 9 December 1907, to Alfred (‘Alf’) Ernest Marples, an engine fitter and later foreman engineer at Metro-Vickers, Trafford Park, and Mary (‘Pol’) Hammond. Alf was a socialist, shop steward and crown green bowling enthusiast while Pol made bowler hats and hatbands at Christie’s of Stockport before her marriage and after giving birth to Ernest. Alf, a close friend of Ellis Smith (later MP for Stoke-on-Trent), was loath to leave his bowling club but in 1923 the family found a new home in Henshaw Street, Stretford. The young Ernest’s upbringing, like all domestic arrangements in this traditional home, was in the hands of Pol, who tirelessly worked for Ernest to ‘make something’ of himself. The house, he later recalled, smelled permanently of boiled cabbage, emblematic of the English cooking of that period. Young Ernest’s entrepreneurial skills were early in evidence when he sold ‘Batty’s Famous Football Tablets’ outside Saturday matches at Maine Road or Old Trafford. His lifelong adherence to the fluctuating fortunes of Manchester City date from this time.

His grandfather Theo, at one time Chatsworth head gardener and seemingly one of a long line of Marples there, also took a lively interest in pets, founding one journal, The Pigeon Fancier, and later re-launching it as Our Dogs, which he ran from an office in Oxford Road. He was chief judge and referee at Crufts for many years. Ernest often stayed at his grandparents’ old beamed cottage in Hazel Grove and seems to have adored his grandfather.

His schoolfellows, perhaps with the benefit of hindsight, later recalled a small boy with fair hair, self-assured to the point of overconfidence, irrepressible, interested in making money and capable of doing anything well. By the time he was sent to Victoria Park elementary school, he must already have acquired his lifelong habit of early rising. There he was taught by Dr John Corlett, a former National Union of Teachers (NUT) organiser. Corlett was to enter Parliament at the same time as the younger man, though his tenure as Labour MP for York was brief.

Walking and rock-climbing seem to have been a passion from early on. By the time he was at secondary school the young Ernest (never Ernie) was part of a group of boys from the Manchester suburbs, ‘the Bogtrotters’, who were committed to major walking and climbing expeditions in the nearby Peaks, the Lake District or North Wales, which places they reached by train or bus. They were not above straying into the Chatsworth estate, though being young and fit were never caught by Theo’s successors. As a young man he also excelled at ballroom dancing, later claiming to have won several prizes. Contemporaries recalled him as a fitness fanatic, forever climbing, cycling or skiing when not fishing in nearby canals. These pursuits would be added to, once his income was secure. Pol, who tended to be over-protective, worried about his climbing. In the end he had to steel himself against the maternal embrace. When he finally left for London she was in floods of tears.

A scholarship to Stretford Grammar followed but the school could not hold him. He later recalled running away to find work with a steamship company, thus (in his words) ‘sacrificing a good, free education on a scholarship for quick cash gains’. The folly of this bargain was pointed out to him by one of the clerks and he returned to school. Another example of his early entrepreneurship was a holiday job as gatekeeper at the local football ground. The fruits of his experience were, he claimed, recorded in a notebook entitled ‘Mistakes I have made’. When he did leave school he was articled to an incorporated accountant in Manchester, passing his final examination as a chartered accountant in 1928 at the age of twenty-one. Some of his work was in Liverpool; while doing that he lived at 16 Church Street, Wallasey (a local connection he would be careful to point out to voters in 1945). Auditing the books of bankrupt firms gave him (he later drily claimed) important insights into the behaviour of nationalised industries.

He then decided to seek his fortune in London, departing with only £20 in his pocket, borrowed from his mother. There he stayed at the Tottenham Court Road YMCA while he found work as a trainee accountant. Possibly at this time he also took a part-time job as a bookie’s clerk, an occupation that eventually led to him learning tic-tac. Indeed he briefly became a bookie himself, offering odds on horses and dogs at White City. The year 1930 may have been a turning point. Ernest obtained a mortgage for a small house in Notting Hill and then let it as a bed and breakfast location to cover his outgoings. He lived in the damp basement and cooked the breakfast himself, carrying it upstairs on trays. But, as he later recalled, ‘I lived free and my time was my own to tackle a deal.’ Other Victorian house acquisitions followed in better areas such as Bramham Gardens, with the young landlord converting them into flats. By 1934 he had moved to 18 Courtfield Gardens, SW5, which became home for two years. His observation of construction gave him a useful practical knowledge of the building trade. He still found time to turn out for Dulwich Hamlet, a noted local amateur football team.

Fate now intervened. While climbing rocks near Tunbridge Wells he met Jack Huntington, a civil servant, the two forming what Ernest himself dubbed ‘a close and intimate friendship’ that lasted over thirty years. Huntington was fourteen years Ernest’s senior yet seems almost to have adopted the younger man. It appears to have been a genuinely Socratic relationship. They shared a flat before the war; after the war Huntington lived in a house owned by Marples. As Marples tells the story Huntington treated him to his first dinner at the Café Royal in gratitude for making him train and improve his fitness as a climber. Huntington extended the younger man a substantial loan to facilitate the establishment of Kirk & Kirk, a contracting business. ‘Hunti’s’ bounty was greater still, for he expanded the cultural and intellectual horizons of the young Ernest, introducing him to Marcus Aurelius, Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas.

On the eve of the Second World War Ernest’s most major project to date, the erection of a modern block of 130 flats with bathrooms, was completed. The new acquisition, Harwood Court, was in the Upper Richmond Road, London SW15, a Putney property he would retain until the 1970s. Ernest lived at No. 3, his last London address before joining up.

By the standards of the time, the young Ernest Marples was an experienced traveller. There is photographic evidence of him climbing mountains in Austria in 1936, 1937 and 1938; in the Bavarian Alps in 1936; and, shortly before the war, observing German house prefabrication methods at close hand. He first reached his beloved Davos, Switzerland, in March 1939 and as early as 1934 he may be seen sailing to the Canaries on a trip that also took in Madeira. He later claimed ‘a first-hand knowledge of Germany and Germans’ due to his enthusiasm for and experience of mountaineering there.

An agile, active and increasingly prosperous young man was not likely to lack female companions. He may have known several young women during the 1930s, including one in Switzerland. While little is known of his first marriage to Edna Florence Harwood on 6 July 1937, he had known her for at least three years: she had joined him in Austria in 1934, on a 1935 climbing holiday in the Lakes and another such in Austria and Switzerland the following year; the well-travelled pair visited Paris in 1937 and even reached Dakar before war ended such trips for the duration. At the time of their marriage Edna may only have been sixteen, though photographic evidence suggests her physical maturity. If this is so, her parents’ consent would have been required. The couple set up house in Pembridge Gardens, Notting Hill.

By 1938, Ernest had become (in the words of his Oxford Dictionary of National Biography obituary) ‘a man of some substance’. With Huntington’s financial assistance he now diversified from landlordism into building contracting. His new firm, Kirk & Kirk, had taken on the erection of the Poplar power station, a project doomed to be delayed by the outbreak of war. More significant yet, Kirks employed a young consultant, Reginald Ridgway. Their meeting would prove to be the foundation of Ernest’s post-war financial independence and wealth.

In July 1939, still only thirty-one, he volunteered for the London Scottish Territorials, and was posted the next month to the 3rd battalion 97th AA regiment. He was a gunner, later appointed to 368 heavy anti-aircraft battery. He rose to be battery quartermaster sergeant and (eight months after joining up) regimental sergeant major, later claiming this was a regimental record. Late in January 1941 he was discharged as a warrant officer on appointment to a commission, transferring to the Royal Artillery as second lieutenant (becoming substantive lieutenant in November). The Marples thoroughness was soon on display. Francis Boyd (later of the Manchester Guardian), who served under him, thought him the only efficient officer in the battery and observed his resentment at his lower status among fellow officers. He still had a Manchester accent and the coming years were to replicate this pattern of disparagement within the Conservative parliamentary ranks. By June he had been promoted to acting captain but rose no higher. He never saw combat. On 17 November 1944 he was invalided out of the army after sustaining a bad cut to his knee which had become infected with tetanus. He left with the honorary rank of captain after war service lasting five years and four months, all of it in Britain. He was awarded both the Defence Medal and the standard War Medal 1939/45.

For many, wartime service with its experience of collective action shifted their thinking to the political Left. Ernest of course had a solid Labour background so might have been expected to reproduce this political trajectory. However, he did not serve overseas and while he certainly saw action as an AA battery commander, he did not face the enemy on the battlefield. Moreover, his pre-war experience was quite distinct from that of his parents and not just spatially. When in later years he spoke of his father he presented the older man as resistant to change whereas his own adult work experience had been of self-help. All this may have contributed to Captain Marples’ inclination not to shift Left. Once recovered from the tetanus, still only thirty-seven and ‘full of vigour’, he knew there would be a general election before long, though he could not have foreseen that Labour would precipitate it by withdrawing from the coalition while hostilities still raged in the Far East. The UK, especially its major cities, was substantially bombed-out. A gifted entrepreneur with a track record in building would surely find ample opportunities in poorly-housed Britain.

We may speculate that Ernest’s marriage to Edna had not been a happy one. He had of course volunteered just two years afterwards; many husbands waited to be called up. There followed six years of postings around the UK. While the couple certainly holidayed in Scotland in 1942, Ernest, for whom leave would have been restricted, was clearly seeing other women and going on Scottish holidays with them. The marriage was dissolved in 1945.

Yet Captain Marples opted for a political career. His ability to combine it with continued entrepreneurial activity would be demonstrated only later. But where? Though it was seventeen years since he had left Manchester his roots remained there and many friendships from his earlier life persisted. Moreover, the north-west was broader than the two great metropolitan cities which dominated, and contained many constituencies that had retained their Conservative allegiance through the inter-war years; there had been no general election since 1935. Suburban Manchester certainly offered possibilities to a young man with a good war record. Then there was Liverpool, a largely Conservative city that still reflected its former aristocratic patronage. Beyond Liverpool lay the spacious suburbs of the Wirral, with their apparently impregnable Conservative constituencies. If he was going to play to the regional strengths that marginalised him in the army, Captain Marples was spoiled for choice.

The path which took Ernest to the Wallasey nomination is obscure. The constituency was a county borough (then located in Cheshire) comprising small towns snaking along the top of the Wirral and linked by the railway tunnel under the Mersey to Liverpool; it excluded Birkenhead. The seat had been safely Conservative between the wars, lately represented by Lieutenant Colonel Moore-Brabazon. But Brabazon had succeeded to the peerage, precipitating an April 1942 by-election. This contest had been triumphantly taken by former Wallasey mayor and local councillor George Reakes, standing on the Independent ticket. In this Wallasey adhered to a pattern of revolt in English towns, some of them later emblematic of Conservatism.

Though it had been ruptured by 1939, Reakes’ background was vintage Labour. His early patron had been Walter Citrine, one-time Wallasey parliamentary candidate and general secretary of the TUC during the 1926 General Strike. Reakes secured election in 1942 as an outspoken backer of Churchill, advocating a vigorous prosecution of the war, though – in a pattern that would continue – Churchill necessarily endorsed the unsuccessful Conservative candidate. There had certainly been discontent among the local Conservatives at having a carpetbagger thrust upon them. By 1945, with the national party truce abruptly ruptured, Reakes might have survived by reverting to his Labour allegiance, but he was estranged from local party leaders whom he had tactlessly described as ‘a collection of potted Hitlers’. In Wallasey as elsewhere Labour was determined to put up a candidate, thereby severing him from a potential area of support. While continuing as a National Independent candidate, Reakes declared in his election address that ‘on all major issues I supported Mr Churchill and the National Government’. ‘A vote for me,’ he added, ‘is a vote for Mr Churchill and Mr Eden.’ His actual programme, reflecting the national mood, resembled Labour’s, for he advocated common ownership of land and mines while opposing the ‘nationalisation of our daily life’.

Wallasey Conservatives were determined to recover a seat they had lost in 1942. In this era before the Maxwell-Fyfe reforms it did an aspiring Conservative no harm to be a man of means. We know Ernest visited Conservative Central Office in February 1945 and he must have been adopted in Wallasey soon after, because by March he was putting himself about in the constituency. From April until polling day (5 July 1945) he spent whole weeks there. The first task he faced was to demarcate himself from Reakes. It was therefore something of a triumph to elicit a telegram from Churchill himself which was then reproduced as an election leaflet. ‘In reply to your enquiry,’ the war leader wrote, ‘I do not look upon your oponent (sic) Mr Reakes as in any sense a supporter of mine.’ Down in London, Huntington had unearthed an interesting political fact – that Churchill, in seeking to reverse a defeat on education policy had sought and obtained a March 1944 vote of confidence in the House: Reakes had on that occasion opposed him. Here was the Achilles heel of a candidate who vaunted his support for the Prime Minister. As Marples tells the story, he kept pressing this inconsistency until ‘Reakes’s confidence oozed away’. To Marples there were only three issues at stake: support for Churchill, the establishment of a permanent headquarters in Wallasey, and his own relative youth and service (at thirty-seven he was far younger than the fifty-six-year-old Reakes, while the Labour candidate was past sixty). His campaign was not without personal mishap, including a climbing misadventure in Snowdonia from which he did not extricate himself until 3 a.m. When Wallasey declared on 5 July 1945, Marples had won comfortably with 18,448, nearly 43 per cent of all votes cast. But the incumbent Reakes still took 14,638 and the Labour-Co-op candidate almost 10,000. Ernest’s own recollection of the election focused on the 1944 no-confidence vote, but arithmetically the truth lay rather with Reakes who, when seconding the vote of thanks to the returning officer, remarked, ‘Mr Churchill has won Wallasey with the aid of the Co-op and Mr Marples gets the divi.’ For Ernest Marples, no subsequent Wallasey election would be closer.

The wartime government had faced a major challenge to ensure that some 3 million men under arms were not, as in 1918, often unable to cast their ballots. As a result, voting was staggered through July and the national picture emerged only on the 26th of that month. It revealed, startlingly, a huge surge to Labour. Attlee’s party had won the popular vote for the first time and, more important, gained a crushing predominance in the House of Commons. Captain Marples’ initial experience of full-time politics would be in Opposition to an unprecedentedly powerful Labour government.

Chapter 2

‘I have done a certain amount of building myself …’: Marples in Opposition, 1945–1950

Even on the Left it is now accepted that the astute Attlee erred by partnering housing with health in his government. Labour’s determination to build a national health system required great energy, leaving little time for housing. Creating the National Health Service was a full-time political job, given to Attlee’s most energetic and charismatic minister, Aneurin Bevan. Bevan himself saw the two policy areas as inextricably combined. This giant department was only broken up in January 1951, by which time Bevan had been replaced by Hugh Dalton. He had clashed with Bevan over whether a council house should have one or two WCs. Bevan’s insistence on two led Dalton to deem him ‘a tremendous Tory’ (see Thomas-Symonds, Nye: Political Life of Aneurin Bevan, 2015). Ultimately, this failure to focus on housing performance would prove electorally fatal, giving Marples, and the Conservatives, their opportunity. For now, their parliamentary attention was fixed on the scale and dominance of the new administration.

From the time of his election, Marples worked assiduously to make his mark. This was not easy in Opposition. His party was bruised by unexpected defeat with a large margin. What was an ambitious thirty-seven-year-old to do? His approach reflected his pre-war experience and wartime experience: the need to get organised. First he needed a London base. In this era, in-house working accommodation for MPs was scarce and beyond the expectation of newcomers. To build a reputation for the assiduous constituency work promised to his Wallasey voters he needed a London office. With his significant personal resources he would not need to skimp. He required easy access to the House of Commons and accommodation large enough to function both as home and constituency office. Identification of the ideal spot seems to have taken some time, but by 1947 he was installed in 33 Eccleston Street, London SW1, a short bike ride from Parliament for a fit and energetic man. This distinguished house, part of an early nineteenth-century stuccoed terrace, was three bays wide and included an attic and a basement. Decorating the first floor of the whole terrace was a beautiful continuous cast iron lotus pattern balcony. Marples filled the interior appropriately, acquiring Regency furniture, including a bed reputed once to have belonged to Queen Caroline, sister to Napoleon Bonaparte. Some of its furniture appeared in the 1948 British film The First Gentleman, starring Cecil Parker. In time Eccleston Street would become more than his office. It would provide a married home for him and his second wife Ruth, as well as an admirable space where the Conservative Great and Good might sample Fleurie wines and fine dining while mingling with celebrities. Eventually it became an important dining venue for political guests starting, in July 1948, with Anthony Eden. At one point in the mid-1950s the couple even had a beehive on the balcony (Marples’ ebullient claim the bees gathered nectar from Buckingham Palace gardens remains unproven). By the 1960s they were a celebrity couple. He had become a good cook, but Ruth was even better. Great care was taken over the menus. Efficient record-keeping ensured that guests were not served the same menu twice. Nor was their home open only to Conservatives. Labour figures like Charles Pannell crop up, plus industrialists and academics, like Beeching and Crowther. The E...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 From Lancashire to the Army 1907–1945

- Chapter 2 ‘I have done a certain amount of building myself …’: Marples in Opposition, 1945–1950

- Chapter 3 Power in Sight

- Chapter 4 Into Government: Housing, 1951–1954

- Chapter 5 Pensions and Pasture, 1954–1957

- Chapter 6 Postcodes and Premium Bonds, 1957–1959

- Chapter 7 Roads to 1939

- Chapter 8 Roads in the 1950s

- Chapter 9 Railways, 1918–1939

- Chapter 10 Railways, 1945–1955

- Chapter 11 BTC Modernisation Fails

- Chapter 12 Superseding The British Transport Commission, 1959–1961

- Chapter 13 Beeching Goes Public

- Chapter 14 The Beeching Report

- Chapter 15 Private Life at the Ministry of Transport

- Chapter 16 After Beeching: Barbara Castle and The Railways

- Chapter 17 Seeking a Role, 1964–1978

- Bibliography

- Plate Section

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ernest Marples by David Brandon,Martin Upham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.