![]()

Initial Burying of the Dead

CHAPTER ONE

July 1-8, 1863

In the turmoil of combat, dead bodies splayed in the no-man’s land between two armies had little chance for burial, but even those behind the lines were often left unburied because the men were exhausted or were ordered to march toward the Potomac River. Dead bodies render a universally revolting stench and also create a potential for the spread of disease. Burial as quickly as possible became a priority.

Men fought for each other, cared for each other, and suffered when a comrade perished. Whenever possible, soldiers scoured the battlefield looking for a comrade and when found, provided a loving burial. These graves were dug deep, lined with blankets or knapsacks, the body carefully lowered into the hole and then covered again with blankets or other accoutrements. Placing a headboard on the grave was the last step in the process.

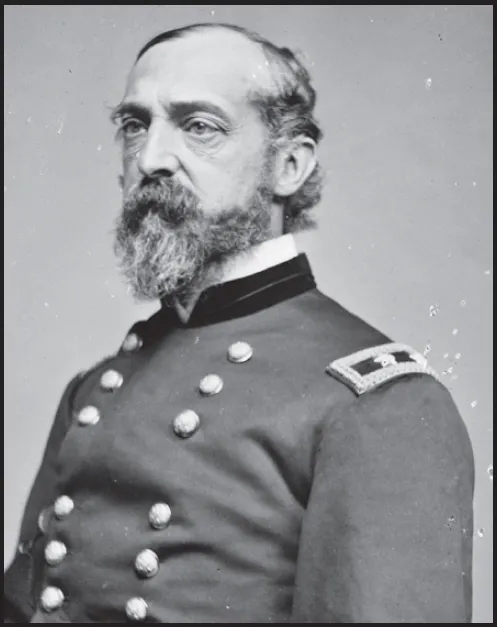

This careful burial was rare, however. The task of tending to so many bodies was overwhelming, and most were thrown unceremoniously into shallow graves. This was especially true for Confederate dead. A soldier on burial detail bemoaned the fact the dead “were on every side of us… . They were so many it seemed a gigantic task.” Army commander General George Meade reported his men buried 2,890 Confederates. This number does not include the considerable number buried by members of the XI and XII Corps and those interred by their comrades prior to leaving the battlefield. He did not supply the number of his own men buried but the number would have approached that of Confederates placed in the ground. Thousands of fallen remained and became the job of the army’s provost marshal, Brig. Gen. Marsena Patrick, who mobilized all his resources to get the job done.

Philadelphian George Meade was a West Pointer whose distinguished career as brigade, division, and corps commander led to his elevation as commander of the Army of the Potomac a mere three days before the battle. He would continue commanding the army through the end of the war. (loc)

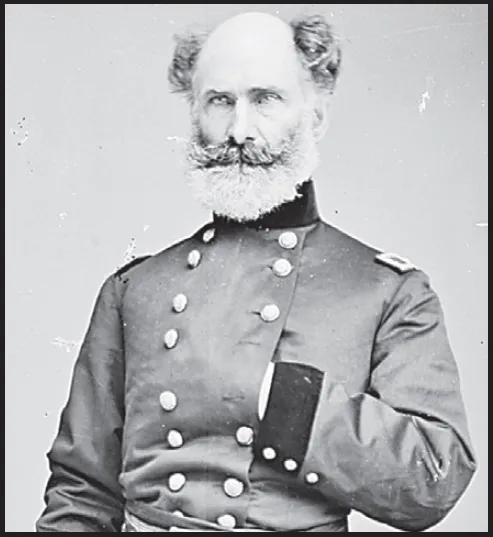

Four groups were pressed into service to bury the dead: soldiers, the provost marshal, Confederate prisoners, and civilians. The paltry amount of available manpower made the job near impossible. Patrick threw up his hands during a meeting with Gen. Meade on July 5 and admitted he was having difficulty completing the immense task. He authorized some of his officers to go into town to organize burial parties, but they could find few takers. He later wrote, “Had a great deal of difficulty in getting hold of some respectable parties to do anything with, the people being nearly all Copperheads [Southern sympathizers]. In desperation, Gen. Patrick convened a meeting of the town’s leading citizens at attorney David Wills’s office and they identified Samuel Herbst as just the man for the job.

The provost marshal continued burying the dead and enlisting civilian help. A reader of the Adams County Sentinel during the week after the battle would have come across this advertisement:

To All Citizens

Men, Horses and Wagons wanted immediately, to bury the dead and to cleanse our streets, in such a thorough way as to guard against pestilence. Every good citizen can be of use by reporting himself, at once, to Capt. W.W. Smith, acting Provost Marshal, office, N.E. corner, Centre Square.

The advertisement attracted only a few volunteers, but several others were pressed into duty when found illegally collecting guns and accoutrements from the battlefield and even rifling the dead’s pockets.

Marsena Patrick was a West Point graduate who left the military to become a railroad president, successful farmer, and college president. He rejoined the army at the outbreak of the war and rose to the rank of brigadier general, commanding a brigade at the battle of Antietam. He served the remainder of the war as provost marshal of the army. (loc)

The job of burying the dead was so immense a visitor to the battlefield seven days after the end of the conflict observed many Confederate corpses still lying about, decomposing rapidly. Indeed, the provost marshal details could bury but 367 Confederate dead and 100 horses between July 8 and 12. The burial of Confederate dead extended well into July.

Burial crews roamed the battlefield to locate and quickly bury the dead. These corpses were probably located near the base of the Round Tops. (loc)

The men assigned to burial details avoided any direct contact with the corpses. William Baird of the 6th Michigan Cavalry explained it was a “very trying job as they had become much decomposed” and Bay Stater Robert Carter described the ghastly details of dead “so far decomposed … as they slid into the trenches, broke apart, to the horror and disgust of the whole party, and the stench still lingers in our nostrils.” The men devised a variety of methods to get the bodies to the burial sites. Baird and his comrades used a “stretcher … made of two poles sixteen feet long with a strip of canvass sowed [sic] to them in the middle long enough to carry a man.” Upon reaching a corpse, two men would lay the rails upwind from the body and a third used a pike to push the body onto the canvas.

The bodies of comrades were often buried with some form of identification. The bodies of these South Carolinians had headboards to reveal their identity. (gnmp)

Burial details after the battle were primarily interested in getting the corpses into the ground as soon as possible. They lined the bodies in rows, dug trenches, and deposited the bodies in them. (loc)

Men dug a variety of graves. According to Alanson Haines of the 15th New Jersey Infantry, “a grave was dug beside where the body lay, and it was merely turned over into the narrow pit. Sometimes long trenches were dug, and in single lines, with head to foot, one corpse after another was laid in; then the earth was thrown back, making a long ridge of fresh ground.”

Sgt. Thomas Meyer of the 148th Pennsylvania Infantry explained another way of disposing of the bodies:

Some of the men buried the dead thus laid in rows; a shallow grave about a foot deep, [was dug] against the first man in a row and he was then laid down into it; a similar grave was dug where he had lain. The ground thus dug up served to cover the first man, and the second was laid in the trench, and so on, so the ground was handled only once. This was the regular form of burial on our battlefields. It is the most rapid, and is known as trench burial and is employed where time for work is limited.

After the armies left Gettysburg, the immense task of burying the dead became more difficult. The provost marshal resorted to an ad in the newspaper to attract volunteers, but there were few takers. (gnmp)

Many of the dead were shipped home to be buried close to their loved one. A J. M. Fisher paid the Adams Express Company to transport a corpse to Delaware. (gnmp)

There was no time for mourning or prayer. Robert Carter lamented the fact “most of them were tumbled in just as they fell, with not a prayer, eulogy or tear to distinguish them from so many animals.”

Coping with the overwhelming number of dead forced the grave-diggers to take shortcuts. Nurse Jane Boswell Moore volunteered her services at a Union II Corps hospital and with some free time on July 26, she decided to roam the battlefield at the site of Pickett’s Charge:

We walk along the low stone wall or breastworks … the hillocks of graves—[and] the little forest of headboards scattered everywhere… . Oh how they [the Confederates] must have struggled along that wall, where coats, hats, canteens and guns are so thickly strewn, beyond it two immense trenches filled with rebel dead, and surrounded with gray caps, attest the cost to them. The earth is scarcely thrown over them, and the skulls with ghastly grinning teeth appear, now that the few spadesful of earth are washed away.

About a month later, Baltimore resident Ambrose Emory also wandered the battlefield and noted near Little Round Top “men not half buried. It may be a skull, an arm, a leg protruding from the ground, barely in many instances covered over.”

Although the Union dead were reburied in the Soldiers’ Cemetery, the Confederate dead remained in the fields until the 1870’s when thousands were sent south to be buried in Confederate sections of cemeteries. (loc)

Comrades felt compelled to mark the bodies or graves with the names of the fallen, hence Moore’s description of the “forest of headboards” described above. These belonged to fallen Union soldiers and helped loved ones find their b...